In 2013, Delonda Anderson conducted an interview with David Madden, published in Pellissippi State Community College’s Imaginary Gardens Literary and Arts Review. The following is Part II of that interview.

THE INTERVIEW – PART II

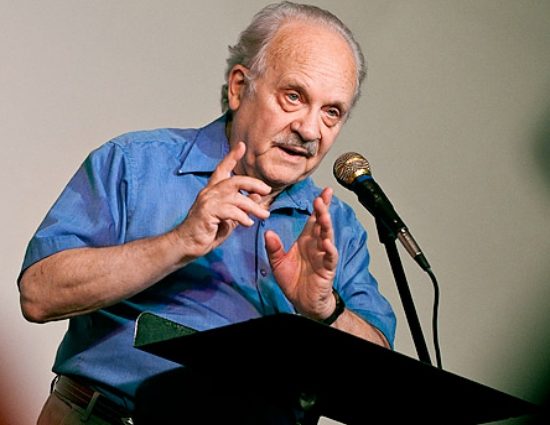

David Madden (MADDEN) – The interviewee

Delonda Anderson (DA) – The interviewer

DA: Some writers express anxiety about creating characters of the opposite sex. Male writers worry about developing credible women characters; female writers wonder whether their men characters are authentic. Yet, you seem comfortable adopting the personae of women. I’m thinking, in particular, of your protagonist, Ann Harrington, in The Suicide’s Wife and the viewpoint character, Cassie, in Cassandra Singing. Do you have advice for novice writers about how to create viable characters of both sexes?

MADDEN: Starting with the writing of my first novel, when it was from Cassie’s point of view, and later in many short stories and novels, The Suicide’s Wife and Abducted by Circumstance, I have never hesitated to write from deep within a woman’s psyche, and so far no one has hurt my feelings by reproaching me with failure, I am glad to say. I am now into a novel about my mother, from her POV. My lack of hesitation in conceiving, starting, writing, and revising fiction from a woman’s POV derives readily from the fact that I have always believed in the supremacy of the imagination over the facts of life and that imagination is actually the subject or one of the subjects of all my fiction. I have never written from the point of view of African-Americans, Native Americans, or Asians, but if a character out of my imagination stood up in front of me, I would not hesitate. Actually, I know individuals of all races and ethnic groups much better than I knew the man who built London Bridge in the 1170s or the poet and others who lived on that bridge through plague and fire, but there they stand, I hope, as real as you and I. So my advice to novice writers is that they know more than enough about the other sex to begin; work out any problems in revision. More and more forces are at work in universities’ courses in all fields and writing programs that constrict young writers. “Writers of the world rebel. You have nothing to lose but your chains.”

DA: You’ve written novels about such topics as adolescence, suicide, and also one man’s musings on the origin and history of the London Bridge. At the risk of oversimplifying the creative process enabling you to tackle a spectrum of subjects, how do you generate story ideas and; how do you know you’ve discovered something you’d like to explore further?

MADDEN: Subjects in themselves never command my attention. I begin with a conception or a character who may be an adolescent or relative of a suicide or obsessed with a subject, such as the bridge, or the movies, or being a merchant seaman, or witness to an abduction. My files are chocked full of stories I will not live to write, and I embraced each of them instantly. When I first saw ancient London Bridge on which three hundred shops and houses had been built, I knew I would write about it; that idea gestated for thirty years and took twenty years to become a published book. Out of nowhere came the image of a woman witnessing the abduction of an older woman – I immediately made notes, then started writing soon after. Fifty years ago, I heard about a man who killed his rival and his own family in the mountains, and never doubted I would write his story. I am now deep into it. When someone at a faculty party announced that a colleague had been found in the woods in the snow shot dead by his own hand, I plunged a minute later into the mind of the wife of a suicide, a woman totally different from my colleague’s wife. What I say here of my own ways of writing applies to many other writers, I suppose, but not to all writers as I know their methods from knowing them or reading about them.

DA: Undoubtedly, you have to have a penchant, a fondness, for some of your characters more than for others. Which of your characters are your favorites and why?

MADDEN: Oddly, I am very fond of my autobiographical personae because they are so transformed that they have become independent characters. Although I was keenly aware of ten or so real people and literary characters who resemble her in one way or another, Cassie is so fully imagined that every time I go back to my hometown in Knoxville, where the novel was originally set, I drive slowly by the house where I first imagined her living, and I think of her as a real person still living there, now my own age, seventy-nine. One time driving by with my nephew in the car, I told him a story of my going into the kitchen of the house, thinking it was abandoned, hearing a voice from another room call out, “Is that you, Lone?” her brother. “No ma’am, it’s just be, David Madden.” “Well, get yourself in here and sit a spell.” I see I am writing a sequel to Cassandra Singing right here in this interview, maybe to be entitled, “Cassandra Dying.” No, too sad. I want her to be as alive as I am this morning.

DA: As you know, Pellissippi State adopted your novel, Sharpshooter, as its common book selection several years ago. Set in the Civil War during the Battle of Knoxville, Sharpshooter is the story of Willis Carr, a Confederate sniper, who is never certain whether he was the marksman who killed Union General William Sanders on the Kingston Pike in 1863. Given Willis’ perpetual uncertainty, what are you suggesting about the role of memory, fact, and fiction?

MADDEN: By dramatizing the nature and activity of fact, memory, and fiction right there in the novel as it unfolds through the sharpshooter’s first-person narrative, written over fifty or so years, I also suggest, as you suggest, a great deal more. I make a fiction of the facts, as fragments found on the battle field, so to speak, and of his faulty memory in such a way as to make the facts no more important than the fragments of memory, so that what is remembered imperfectly and what is imagined is as real as any fact. The same is true to a lesser extent (I imagined him to be basically unique) of other veterans and home front folks, too, and of Americans looking back, especially now, into the fourth year of the 150-year anniversary of the end of the Civil War. Imagination acts upon, changes, enhances what is remembered and what the facts are or seen to be (in life, every soldier remembers differently, and in histories, every rendering of every battle reads differently). Imagination and memory swamp facts, and the product becomes a kind of fact, a memory is a fact, as when each of fifty or so soldiers on each side wonder whether it was his stray bullet that accidentally killed Stonewall Jackson. If a historian should discover whose bullet killed Jackson, that fact could not compete with the matrix of imagined – remembered versions of what happened.

DA: Let’s return to your novel, London Bridge in Plague and Fire. This book is an imaginative tour de force in which a young poet, Daryl Braintree, living in London in 1665, tries to imagine the life and times of Peter de Colechurch, architect of London Bridge, living in the same city in 1176. Your use of the frame technique, or the story written within a story approach, is fascinating. Would you discuss how and why you chose to tell the story in this fashion?

MADDEN: Both the poet and I pursue the facts obsessively but the found facts stimulate our imaginations with greater force and our obsession with our imagined versions of the facts is stronger as when the poet, who has like myself found no facts that link Peter to St. Thomas Becket, imagines a relationship between them that is so meaningful to Peter that he steals and conceals Thomas’ body. The facts of the murder are available in detail for both the Poet and myself, but no facts are known that the body was ever stolen. The seemingly factual abduction of the two girls is purely an act of imagination by me and the poet. I render stories within stories and I imagine the poet doing the same. All that evolved over twenty years and ten major revisions of the novel as a result of the nature of my narrative imagination and my technical, artistic imagination reaching out into many possibilities. It’s that I am who I am – I am she whose mind and imagination naturally works that way.

DA: One final question: What advice do you have for young writers embarking on a writing quest?

MADDEN: Every successful writer and teacher of writing (one and the same these days, well, since about 1948 or so) will say, “Read fiction all the time, both as your tastes incline, but mainly as a writer, studying the techniques all or most writers use, in one way or another. Read Henry James, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Virginia Woolf, and Faulkner for point of view and style, and other techniques, such as imagery, juxtaposition, context and implication . . . And write something every day, without fail. Eventually, settle into a routine.” My personal emphasis is upon learning the words for aspects of technique so that you always have something to do in the revision process. Knowing technique, you always have thrilling experiences in the revision process. Writers write words. Amateurs write stories. Writers write words.

A closing from Delonda Anderson:

It was my great pleasure and honor to interview David Madden. He was kind and gracious throughout the process. And meeting him was such an unforgettable experience. He is a true Appalachian novelist, one whose wisdom, artistry, genius, and imagination spans the written page. I am so very grateful.

Check out the David Madden’s latest published works:

Find information about his bibliography, awards, and prizes here.

Where to purchase David Madden’s books:

Union Avenue Books, Knoxville, Tennessee

**PHOTO SOURCE: davidmadden.net/ Photographer Blake Madden