INTRODUCTION

In 2013, Delonda Anderson conducted an interview with David Madden, published in Pellissippi State Community College’s Imaginary Gardens Literary and Arts Review. The following is Part I of that interview, with a tweaked introduction that also accredits work he has accomplished since then.

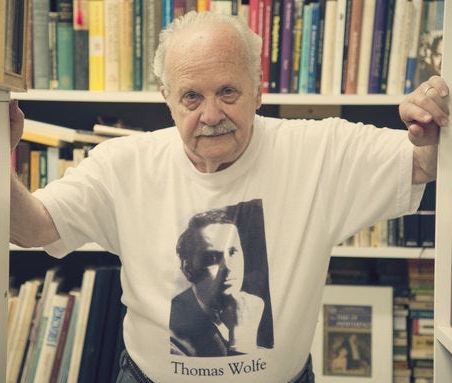

On a frosty winter day, one might see eighty-six-year old David Madden looking every bit the author in a smart, tweed jacket, and sporting a suave fedora, underneath which lays the machinery of an inexhaustible mind and literary genius. One need only glance into his wise, deep eyes to see the flicker of visual gears that work ideas and set his next literary masterpiece in motion. Author of thirteen novels, and a two-time Pulitzer Prize nominee, Madden has acknowledged that his experiences in his home city of Knoxville, Tennessee, often provide the impetus for his characters, like Willis Carr in Sharpshooter: A Novel of the Civil War (U. Tenn. Press, 1996). His personal familiarity with Knoxville’s historically rich and colorful Bijou Theatre furnished the spark for his novel, Bijou (Crown, 1974). Knoxville’s own Gay Street Bridge offered obliging inspiration for London Bridge in Plague and Fire (U. Tenn. Press, 2012). Outside Knoxville, Madden further expands the cultural awareness inside Appalachia’s mountainous region, where upper East Tennessee meets Kentucky coal country in his novel, Cassandra Singing (U. Tenn. Press, 1998), for which he also wrote a Warner Brothers screenplay. His novel, The Suicide’s Wife (Bobbs-Merrill, 1978) was made into a CBS movie starring Angie Dickinson, and a closely related subsequent novel, Abducted by Circumstance was published in 2010.

Since the 2013 interview, the author has published a collection of short stories, The Last Bizarre Tale (U. Tenn. Press, 2014), including a sneak peek to a greatly anticipated Bijou sequel in “A Demon in My View.” His most recent work, Marble Goddesses and Mortal Flesh (U. Tenn. Press, 2017) is a novella that parallels many aspects of his own life. Madden’s forward-looking biography, The Voice of James M. Cain, will be available in spring, 2020. Readers can also expect two of his recently completed works, a memoir, My Creative Life in the Army and another innovative memoir about his mother.

David Madden lives in Black Mountain, North Carolina and is a Robert Penn Warren Professor Emeritus at Louisiana State University. He is an extraordinarily talented person – a prolific writer in all fields – born and shaped in the rolling hills and deep valleys of Knoxville, Tennessee. From novels to short stories, poetry, essays, playwriting, libretti, scholarly works, literary criticism, and edited texts, his literary endowments encompass a full scope of erudition. A person might wonder how Madden manages to continually offer such brilliance to the literary, historical, and creative worlds. What key writing elements, methods, and motivations continue to form the writer who forms the masterpiece, or, perhaps, vice versa? Whether one delights in David Madden’s many writing genres, attends his dramatic readings, or enjoys a simple conversation, an encounter with his brilliance is unforgettable.

THE INTERVIEW – PART I

David Madden (MADDEN) – The interviewee

Delonda Anderson (DA) – The interviewer

DA: In 2006, you were the subject of a book entitled, David Madden: A Writer for All Genres, by Randy A. Hendricks and James A. Perkins. The authors note that you are a novelist, poet, literary critic, and playwright. In fact, you wear as many literary hats as there seem to be existing genres. Do you ever experience difficulty shifting literary ground, moving from genre to genre? Do you enjoy the challenge of exploring different types of writing, often in the context of the same work?

MADDEN: The answer is inherent in my childhood. My first published story was in 1951 when I was about nineteen. By that time, I had written many articles, stories, poems, movie scenarios, and radio and stage plays, and had won a state playwriting contest at seventeen. So, having told stories orally to brothers and friends since age three or four, inspired by my grandmother’s tales, and having started writing stories at age eleven, inspired by the movies, I had quite naturally and easily moved back and forth from genre to genre, without hesitation. I did not really read very much until I was about fourteen, having amassed over a foot-high stack of writings in all genres. Oral storytelling, radio drama, and movies (I became a radio announcer at age fifteen and an actor at sixteen) had been my main inspirations – sound and image media, including magazine fiction illustrations (I had always thought of myself as a visual artist), not the printed word. The force behind all those genre immersions and explorations was an almost primal desire to do unto others as each genre had done unto me – entranced and thrilled me with what I later came to call the Pleasure Dome effect (name of my fifth novel). I am aware that single flow of creative energy has carried me along in all my roles in life and literature. You are among the first to add “often in the context of the same work,” and two good examples are Pleasure Dome (radio, television, and film) and London Bridge in Plague and Fire (poetry and history).

DA: Author Robert Penn Warren spoke of the writer’s need to see the “universal in the particular,” to start with observations in one’s backyard applicable across time, place, and culture. At a dramatic reading at the Bijou Theater, you pointed out that the Bijou was the focal point for your appreciation of theaters throughout the world. Similarly, you said that the Gay Street Bridge was never far from your thoughts when writing your novel, London Bridge in Plague and Fire. Would you discuss the imaginative alchemy enabling you to make connections of the sort you mentioned at your reading – ones described by reviewer Allen Wier as, “woven over water, through space, and beyond time”?

MADDEN: I like your linkage of what Warren (whose All the King’s Men, I admire greatly) and what Allen Wier (my former student whose Tahano is a masterpiece) said, Warren about fiction generally, Wier about London Bridge in Plague and Fire specifically. I agree with them, but what they say is not consciously operative for me ever in the act of writing, and I am, in prewriting and revision, one of the most aesthetically conscious writers I know about. All my work has the effect they describe by other means. For instance, specific images affecting all the senses is what people often cite as a main feature of my writing, and I have developed a concept I call “the charged image,” which is the most powerful expression of the general or universal in the particular. The charged image is what most readers experience most intensely throughout a story, consciously or unconsciously, and is what they remember most readily over time, because it embodies all the elements (character, conflict, setting) and all the techniques (point of view, style, etc.) active in the story: the bridge in this latest novel, the lighthouse in Abducted by Circumstance, the tower in Sharpshooter, the motorcycle wheel in Cassandra Singing. In famous literature, it is Huck and Jim on the raft on the Mississippi River, Don Quixote and the windmill, Gatsby and the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. Yes, Gay Street Bridge and the Bijou Theater are particulars that evoke all the universals in my life and literature, and add to that the tower and the dome.

DA: You are a writer who boldly explores point of view. It is not uncommon, for instance, for your characters to imagine what other characters, some long dead, once thought and said over oceans of time and vistas of distance. In the planning stages of your novels, how do you determine the answer to the question: Whose story is it?

MADDEN: Never having had writers block, I slip-slide readily in the planning state into a point of view character, but often in the many revisions over six or fifteen or twenty years, other characters hi-jack the POV (in third person stories, never first person). Cassandra Singing was really my first novel, but early in its fifteen years of revision, I wrote The Beautiful Greed, my first published novel. Originally, the POV for Cassandra was Cassie, after her brother Lone was killed, and then I let him live in the present through her POV; but in about the seventh year of revision, I shifted to Lone’s first person, and finally to his third person POV, because I wanted the reader to see her more in focus, and so I like your thinking the published novel is from Cassie’s point of view, although technically it’s not. The two novels I wrote in twenty days each started and stayed in Ann’s and Carol’s point of view perspective. Carol’s compassionate imagination compels her to get into the mind of the woman whose abduction she witnesses. The most dramatic instance of point of view change came when I set out to tell the Civil War story of Knoxville from the most omniscient point of view ever in all literature and realized that the first and second versions of 1,500 pages was not working. The solution was to try it from the first-person point of view of the sharpshooter, to whom I had devoted only one page in the long versions; I found that his 250 pages achieved everything I set out to do. The two characters I had focused upon in the early versions ended up on only two or three pages. By the way, some scenes are set on Gay Street Bridge and in the hotel that later became the Bijou.

Stay tuned — Part II of “Writing Words: A David Madden Interview” continues . . .

**Photo Source: davidmadden.net/ Photographer: Paul Clark