In my 2016 stage play Which Side Are You On: The Florence Reece Story, I envision a scene at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, wherein union activist and songwriter Florence Reece and Civil Rights reformer Martin Luther King, Jr. are discussing ways for opposing violence. The exchange follows:

Florence

Martin, this Gandhi feller – I read a newspaper piece that said he was a lawyer with a first-class ticket on a train in India. But a station policeman ordered him back to third class.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Yes.

Florence

But Gandhi refused and was arrested.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

That’s right.

Florence

So Gandhi arranged a peaceful protest.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

What we in the Civil Rights Movement call non-violent resistance.

Florence

Us miners would call it a strike. Only this Gandhi feller asked people in India to lay down on the railroad tracks to stop the trains.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Yes.

Florence

The way I see it, Mr. Gandhi was pretty sure of the outcome before he got it. He counted on the British people to be civilized. Civilized people don’t run over people laying on railroad tracks. But if you’re a striking miner in eastern Kentucky and lay down in the road, you can count on some scab to run over you.

Florence Reece was twelve years old when she wrote one of the most famous protest songs composed in America: “Which Side Are You On?”, first recorded by folk singer Pete Seeger in 1941, several years following the Harlan County, Kentucky War, a series of coal-mining related skirmishes, executions, bombing, and strikes during the 1930s. The ten-year long conflict pitted coal miners and union organizers on one side, and coal companies and law enforcement officials on the other. The dispute centered on the rights of coal miners to organize (i.e., unionize) their workplace while agitating for higher wages and safer working conditions.

Reece’s discussion with King reflects her abiding conviction that bullies rarely stop bullying of their own accord. The daughter of a coal miner, and later, the wife of one, Reece knew first-hand the insidious ways coal operators exploited miners and their families. When miners, like her father, joined the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), mine operators locked out union workers, giving their jobs to “scabs,” non-union men willing to work at a lesser wage. Blacklisted miners were also evicted from their company homes. People went hungry.

Coal companies also hired “enforcers,” such as agents of the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency, referred to by miners as “gun thugs,” to harass and threaten striking miners. Gun thugs had no qualms about shooting up workers’ homes with women and children inside. This happened once to Florence and her children when Florence’s husband Sam was away briefly on union business. Their house was riddled with bullets. Florence ordered her children to take cover under their beds. Miraculously, no one was hurt.

Consistent with the history of coal mining in eastern Kentucky is that it took outsiders to sound the alarm about America’s most exploitative, toxic, and dangerous occupation. In this case, journalists Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, and Sherwood Anderson travelled to Harlan to survey the landscape and interview workers and their families. Dreiser described the abuse of miners as no less than “terrorism.” In a December 1931 article in The New Republic, Dos Passos wrote:

Everybody knows that the coal industry is sick and that the men working at our most dangerous occupation (every sixth man is injured in the course of a year) are badly off, but few Americans outside of the miners themselves understand how badly off, or how completely the “American standard of living” attained in some sections during boom years, with strong unions working under the Jacksonville agreement, has collapsed. The coal operators, who have been unable to organize their industry commercially or financially along modern lines, have taken effective common action in only one direction: in an attack against the unions, the wage scales and the living conditions of the men who dig the coal out for them.

Those most exploited but having no say were children. A child in the morning never knew whether his or her father would arrive home safely at the end of the day. Such was the case of Florence Reece’s father who died in a mine explosion. Moreover, children didn’t just experience danger vicariously. Boys as young as eight were employed as breaker boys whose labor-intensive job was to remove impurities in coal by hand. For ten hours a day, six days a week, boys sat on wooden seats, perched over chutes and conveyor belts, picking slate out of coal. They were forced to work without gloves so they could better grip the slick coal. However, the slate was sharp, and breaker boys often left work with their fingers cut and bleeding. Some had their fingers amputated in conveyor belts. Compensation for accidents was nonexistent.

The exploitation of child labor in the early twentieth century didn’t just occur in the mines. In South Carolina, young girls were sent to work in factories shortly after they learned to walk. At one factory, girls shucked oysters from 3:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., standing on their feet all day. One observer described the scenario:

Young girls with grown-up eyes. A very short childhood, no doubt. Heartbreaking.

With the advent of unions and child labor legislation, an outsider might conclude mechanisms were in place to improve the plights of workers and their families. However, that contention overlooks an existential reality: Capitalism is soulless, and the bottom line continues in every generation. Bloody Harlan of the 1930s was significantly no different from the Harlan coal wars of the 1970s. Even some combatants, like Florence Reece, remained in the fray. The Global Nonviolent Action Database summarizes what happened.

In June of 1973, workers at the Brookside coal mine in Harlan County, Kentucky voted 113-55 to replace their membership in the Southern Labor Union (SLU) and join the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) union. The SLU was largely seen as serving the interests of the mine owners rather than the workers.

The owners of the mine, Eastover Coal Company, a subsidiary of Duke Power Company, refused to sign the new contracts, which would have established a UMWA local in Brookside.

Miners establishing a picket line (i.e., a boundary created by workers on strike preventing entrance to the mines) were arrested and given prison sentences. Without their husbands and fathers, women in the community stepped up to replace their men kinfolk on the picket lines. They were threatened with violence and shot at. Gun thugs drew weapons, insisting women step aside, making way for automobiles belonging to non-union scabs.

A documentarian named Barbara Kopple and her cinematographic team settled in Harlan for a time to record the efforts of union members and the abuses of coal miners/ operators. A former VISTA volunteer, Kopple had worked on other documentaries, especially as an advocate for workers’ rights. She filmed some of the most intense and potentially deadly confrontations of the strike. She also showed the unflappable resistance of the Kentucky hill people. At one point, the camera pans to a feisty Florence Reece reminding miners what’s at stake:

I’m not a coal miner as you well know, but I’m as clost to one as I could be not to be one. My daddy died in the mines, and my husband is dying slowly from Black Lung. But he was in bloody Harlan, and, I tell you, it was bloody. I’m here to remind you got nothing to lose but your chains and a union to gain. So I say, Hang in there!

Though insisting she was too old to sing, Reece belted out a raspy rendition of “Which Side Are You On?” to thunderous applause from those assembled. Barbara Koppel’s Harlan County, USA (1976) was a stunning example of journalistic reporting, earning the filmmaker an Academy Award for best documentary.

For three decades I asked my college students what occupations would have been available to them a hundred years ago. The options they discovered were few: farming, mining, or working for the railroads. I asked them to consider what their lives would be like without the protections afforded by labor unions and some visionary individuals who made sacrifices without foreknowledge of future generations benefitting from them. The students were often awestruck by the mystic thread connecting them to a history of struggles they could imagine being their own. Perhaps the keenest insight they gleaned was the solemn obligation each of us has to accept the challenge posed by one immutable question: “Which Side Are You On?”

- Newspaper clippings from Newspapers.com Southeast Edition

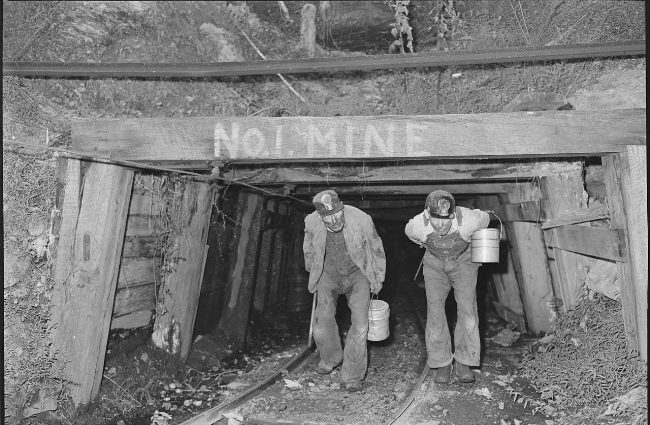

**Featured image – 1946 Miners exit the mine after their shift, Harlan County, KY NARA-541293 – Wikimedia