Two kinds of hollows exist in the mountains. The first kind is the nice, pleasant, winding road that leads to a lake or park out in the boonies. The second kind is an offshoot from that nice road and it snakes down into a deep, dark holler. I grew up in the second kind, a holler within a hollow, if you will.

Our house sat atop a hill, surrounded by trees galore. You name it, pretty much anything outside bamboo or palm surrounded us. The earth was rich and dark, and smelled like sweetness, rain, and mild patchouli. We traipsed through the woods, crossed streams and creeks, and stopped at an amazing little waterfall. We had seasonal foods and medicines from wildcrafting, but, if I listed everything, I could likely fill the whole post.

To be sure, life wasn’t easy. We had our share of hardships, stirred in a batter of trauma, misery, and grief, sprinkled with anger and oppression. Suffice it to say, we knew poverty – dull, abject, and age-old. When something broke, we either fixed it or gave it new purpose. Food had to stretch, clothes had to endure, and shoes had to last.

Yet, none of us were dumb or filthy, as we are often portrayed. Before the internet was a thing, my mother made sure our family had two sets of encyclopedias and we were grateful to have them. The holler even had its own book-sharing system. Whenever our family read and finished books, we traded them with another family, and vice versa. But one book in particular spoke to me like no other at that time. I couldn’t relate, necessarily, to the plot (well, perhaps an element here or there); but I did find commonality with the lifestyle. To this day, it conjures up all those old mountain scenes, smells, and feelings.

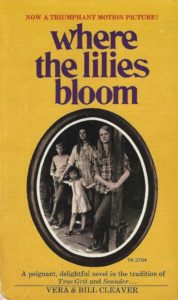

Where the Lilies Bloom is a young adult novel co-authored by Vera and Bill Cleaver, published in 1969 by Harper Teen. The book was a finalist in the National Book Awards for Children’s books in 1970. The story centers around the Luthers, an Appalachian sharecropper family consisting of a widower father, Roy Luther, and his four children: Devola, Mary Call, Romie, and Ima Dean. The land they work is owned by a man named Kiser Pease, who is quite smitten with the oldest daughter, Devola, but Roy Luther objects.

Roy Luther is sick and knows he’ll die soon. Since Devola, is “cloudy headed” (p. 10), he gives fourteen-year-old Mary Call, several big responsibilities: take care of his burial, be proud of who she is, keep the family together, and don’t let Devola marry Kiser Pease. Mary Call becomes the new head of the family and the story develops around her and the Luther children and how they survive and stay together without their father.

Mary Call narrates the story and reveals so many Appalachian customs and ways through her viewpoint. Folk medicine and wildcrafting are a huge part of the story as the children journey in the mountains, collecting herbs and roots, then drying and selling them to the local grocer.

Living in certain parts of Appalachia means living fairly isolated. Lilies addresses the toll this takes on a person. Defeatism and despair are often countered by hope and optimism. At the children’s worst point in the story, Romey says, “The Lord has forgotten us. This land is forgotten. We’re forgotten. We’re forgotten people.” (p. 145) Mary Call, has her own thoughts:

I looked at my brother and I thought, It’s the truth . . . I thought about a man’s hold on life, how painful its struggle . . . And something within me stirred and my spirits lifted . . .

This land isn’t forgotten and neither are we. It just seems like we are out here in all this snow and cold and quiet.

. . . I thought about spring, how it would come again. How the mountains would turn fresh-green again and wave upon wave of returning warblers would come flashing across them wildly singing. The bluets and the trillium and lilies – all of the spring lovelies would bloom again. Spring would come – it always did. (pgs. 145-146)

Appalachian poverty is often propagated within a family. This entrenched impoverishment is addressed near the beginning of the book when Mary Call says of her father: “He’s let things beat him, Roy Luther has. The land, Kiser Pease, the poverty. Now he’s old and sick and ready to die and when he does, this is what we’ll inherit – his defeat and all that goes with it.” (p. 17)

Yet, poverty is countered by a profound mountain connection and clever resourcefulness. When the Luthers need some type of income, they find their mother’s wildcrafting book. Mary Call is inspired:

And with the excitement in me beating hard I carried the book to the cold kitchen and built a fire in the wood stove and sat beside it until the night was gone and read about ginseng and mayapple and goldenseal and all the rest of the medicine plants that grow wild in the green forests of Appalachia – plants which drug companies the world over gladly pay for. (p. 39)

The story also presents realistic experiences within mountain families and doesn’t sugarcoat. Families are united but they sometimes argue and say hurtful things to one another. Stressors are a huge factor. In the book, Mary Call often becomes exasperated with her siblings. When wildcrafting one day, she’s frustrated by their lack of effort, and lashes out at Devola and Ima Dean who leave. So she and Romey are left to finish. Mary Call tells Romey, “I’ve got the worry of all of you on me,” then she and Romey have a heated argument:

Romey shuffled his feet and released a sigh. “Well, I’m sorry you’ve got the worry of me on your mind. I didn’t ask to be born. I wish I hadn’t’ve been.”

“Yeah? Well, maybe you’ll fall off the mountain today and kill yourself and be out of your misery. Get the dishpan.”

Romey thrust his jaw out. “Get it yourself. I’m not your slave. You’re the hatefulest person alive, Mary Call. If Roy Luther was alive you wouldn’t treat us like you do.”

“Just get the dishpan, Romey, and shut your trap. I haven’t got any time to stand around here this morning and listen to you whine. We’ve got work to do.” (pgs. 91-92)

The Luther children endure a series of harsh trials, seemingly one after another, but they do so all together. They find that human will and determination are powerful characteristics. Flaws and weaknesses are part of a humanness that can’t be denied. The mountains provide solace and Earth’s regeneration provides healing in all aspects of their lives.

Aside from the run-on sentences and comma splices, I guess the only thing I didn’t like about the book (though I’m not bothered by it anymore) is the fact that Vera and Bill Cleaver weren’t Appalachian. I didn’t discover this fact until my mid-20s. I was genuinely shocked that writers who weren’t from Appalachia could write something so connected with Appalachia. I’d say any person from these mountains, young or old, who reads the book would agree the story seems to be told from a native of the region. But that they did so makes them good writers worth reading.

Vera Fern Allen Cleaver was from South Dakota and William Joseph Cleaver was from Oklahoma. I found them to be pretty amazing writers, really. Both served in the Air Force. Neither graduated from college, yet they coauthored over a dozen young adult novels with “a particular interest in mountain children,” and they published hundreds of short stories.

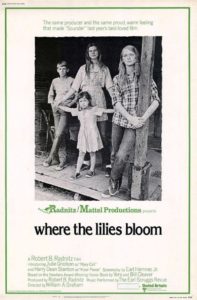

In 1974, United Artists made Where the Lilies Bloom into a movie, filmed in Watauga County, North Carolina, directed by William A. Graham, and starring Julie Gholson as Mary Call; Jan Smithers as Devola; Matthew Burrill as Romey, Helen Harmon as Ima Dean; Rance Howard as Roy Luther; and Harry Dean Stanton as Kiser Pease, among others. The soundtrack was performed by The Earl Scruggs Revue. You may recognize Rance Howard as Ron and Clint Howard’s father. He has 285 credits in his filmography. Jan Smithers went on to play Bailey Quarters on WKRP in Cininnnati, and other television appearances. Harry Dean Stanton has a considerable filmography of 206 credits, a good portion of which are TV westerns. The other three child actors made no more films.

The movie mostly “goes by the book,” deviating here and there without notice, really. I don’t know much about film’s technical aspects in general, but I do know what’s well done. The movie doesn’t disappoint. Several wide shots offer panoramic views of the gorgeous North Carolina mountains. The setting provides an authentic visual and feel. The actors were spot on – with their performances, characteristics, and dialect. Stark differences are presented between the wealthier Kiser Pease and the struggling Luther family.

I can’t find a thing I didn’t like in the movie, really. I highly recommend Where the Lilies Bloom – both the book and the movie. Out of a possible ten stars, I give them both an eleven. You can purchase the book at Union Ave Books, Barnes & Noble, and Amazon, or find it at your local library.

Follow these links to watch the movie and hear the full soundtrack on YouTube.

Book Source: Cleaver, Vera and William. Where the Lilies Bloom. Philadelphia : Signet, 1969.

Featured Image: screenshot of Julie Gholson who plays Mary Call Luther – from www.bonanza.com