A city in East Tennessee rests quite unobtrusive and timeless against a misty mountain backdrop. Historic architecture lines the old main street that once felt the drumbeat of a booming industry. Rocky Top was once Lake City, but the area was originally named Coal Creek. Pioneers first settled the area in the mid-1800s and found the banks by the cool, crisp creek amenable. Every region has that chronicle of events that inevitably defines a place. So it was with Coal Creek, Tennessee. At the turn of the twentieth century, the small, vital city was beset by war and disasters unspeakable and horrific. For Coal Creek, tragedy exposed a buoying people with an inner strength and tremendous fortitude. I’d like to take you on a journey to explore this unique place. First, let’s take a look at the Coal Creek War.

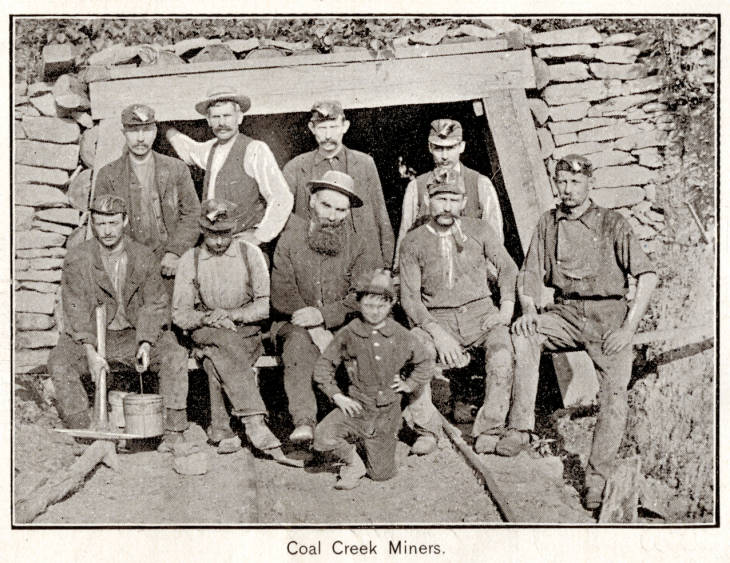

By the 1850s, coal was Tennessee’s major industry, thanks in large part to short-line railroads, and Coal Creek had the most coveted coal of all. It has always been a cheap resource with a big profit. In fact, it was so cheap that anybody who had an iota of wealth took a gamble. And Appalachia was rife with coal—fifty million acres. So, in October, 1867, Coal Creek exported their first railcar of the fossil fuel. After this, coal camps—company owned communities for miners and their families—sprang up across the Appalachian Mountains.

Though coal barons experienced prosperity, the region otherwise suffered. The South and Appalachia were bankrupt after the Civil War, and it just so happened that the prison system was in dire need of reform. Prison upkeep was too expensive and the facilities were overcrowded and dilapidated. To amend the prison dilemma, the Tennessee State Legislature passed a convict-leasing law in 1866. Prisoners were rounded up and “leased” to the coal mines as free labor. They were housed on or near the premises in stockades and kept under guard.

Needless to say, the convict-lease system didn’t set too well with the working miners. As time went on, the miners’ wages and workdays were slashed. Yet, between 1870 and 1890, the convict-lease system stuffed Tennessee’s pockets with close to $770,000 (between sixteen and twenty million dollars today). The miners understood what was happening. Companies paid little to nothing for more work and received greater profits.

A coal miner wasn’t paid by the hour, by the day, or even by the job. A miner was paid by the weight of coal he extracted—specifically, by the ton. Every day a mineworker loaded the coal he extracted into an empty rail car. He put a “small brass tag with his number stamped on it”1)Archbald, Hugh. 1922. The Four Hour Day in Coal. New York: H.W. Wilson Company. P 29 which assigned the load to his name. A weighman worked “at the tipple where the coal was weighed”2)Husband, Joseph. 1911. A Year in a Coal-Mine. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. P 24 and allocated the weight to each miner’s account. The coal miner was then paid with a currency called scrip, which could only be used at company stores in or around the coal camps. If a miner refused to do business with a company store and went elsewhere, he could lose his job.

By 1891, twenty-five years of job and wage uncertainty caused by the convict-lease system and a score of unresolved grievances left the miners with few options. One of the grievances involved the weighman for the Tennessee Coal Mining Company in Briceville. The miners were suspicious of the numbers so, in accordance with Tennessee law, they requested a “checkweighman” to confirm the coal weights and workers’ accounts. The coal company agreed. The miners hired their own checkweighman and the company disagreed. As a further affront, the coal companies tried to force the miners to sign “iron-clad agreements” which just about eliminated all their rights. A signed document meant a miner had no right to a checkweighman, no right to accept a salary of cash over scrip, and no right to refuse to work. But perhaps what angered miners most was the statement that gave the employers unconditional authority and took away the miners’ right to unionize. They refused to sign and, one by one, walked out.

The Tennessee Coal Mining Company responded by closing the Briceville mine in April 1891 and locking out the miners. The company mockingly reopened the mine on July 4—Independence Day—with convict-lease labor. Forty convicts were brought to Coal Creek and ordered to demolish the now evicted miners’ homes and build a stockade for more prisoners.

On July 14, the anniversary of Bastille Day, the miners met to discuss “aggressive action.” After midnight on July 15, three hundred miners successfully besieged the Briceville stockade, collected the convicts and their guards and put them on a train to Knoxville. They sent word to Governor John Buchanan asking for his help. The governor traveled to Briceville “accompanied by a battalion of state militia”3)Cotham, Perry C. 1995. Toil, Turmoil, & Triumph: A Portrait of the Tennessee Labor Movement. Franklin: Hillsboro Press. to hear the miners’ grievances. Unsurprisingly, he offered no assistance. The following day he returned to Nashville but left the militia men in Coal Creek. Status quo continued.

On July 20, around two thousand armed miners stealthily advanced to the Tennessee Coal Mine stockade. Hidden from sight, they sent three men to inform Colonel Sevier, commander of the militia, of their demand for the convicts’ removal. When the Colonel tried to capture one of the three men, that man gave a signal and “at once the two thousand miners sprang to their feet and marched in awesome demonstration to the stockade.”4)Cotham, Perry C. 1995. Toil, Turmoil, & Triumph: A Portrait of the Tennessee Labor Movement. Franklin: Hillsboro Press. The Colonel was outnumbered and surrendered. The miners marched the convicts, guards and militia to Coal Creek and put them on a train to Knoxville. After this, they went to another mine in Briceville and repeated the same actions.

Governor Buchanan traveled back to Knoxville and met with a newly formed mining committee. The miners would temporarily comply with the convict-lease system if they were pardoned for their nonviolent uprisings; and if the governor called a special session of the Tennessee General Assembly urging the overturn of the convict-lease law. Upon return to Nashville, the governor called the special session in August 1891. The legislature denied the miners’ requests, and, further, made it a criminal offense to interfere with convict labor. Anyone who did so faced up to five years in prison. The miners and Tennesseans as a whole were stunned.

On Halloween night, 1500 armed miners disguised themselves and marched with purpose to the Tennessee Coal Mining Company where they released 163 prisoners outright—free—into the hills. Then they set the stockade on fire and watched it burn to the ground. They repeated these actions at the Knoxville Iron Mine, releasing 120 convicts before setting fire to the guard house. They “battered down the stockade door with a sledgehammer”5)Cotham, Perry C. 1995. Toil, Turmoil, & Triumph: A Portrait of the Tennessee Labor Movement. Franklin: Hillsboro Press. at the Cumberland Mine in Oliver Springs and freed two hundred convicts before burning it down. Community sentiment sided with the miners as Coal Creek’s locals provided the convicts with food and clothes.

The coal and leasing companies hesitantly extended an olive branch. They halted their convict-lease participation, rehired the free miners, and restored their rights. The miners and the community were relieved. Peace at last.

In December 1891, however, Governor Buchanan, faced with public criticism, sent the convicts back to the mines with military reinforcements. The stockades were rebuilt stronger and larger and prison workers came to Coal Creek once again. The miners resumed work but, little by little, injustices grew within the coal walls. The prisoners were forced to work full time while the free miners worked part time, a scant one to three times a week. Any miner who participated in the uprisings was “blacklisted” and fired. The best places in the mine to work were given to “scabs and blacklegs.”6)Cotham, Perry C. 1995. Toil, Turmoil, & Triumph: A Portrait of the Tennessee Labor Movement. Franklin: Hillsboro Press.

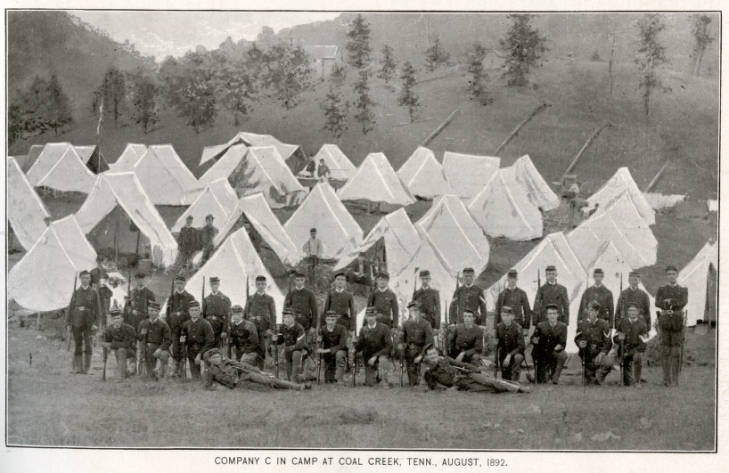

In August 1892, the situation erupted for a final time. The Tennessee Coal Iron and Railway Company cut a good portion of the free miners’ workload by half. Mineworkers all over the region were outraged. They trekked to the stockades, overpowered guards, looted, gathered convicts, put them on a train to Nashville, then torched the buildings. The situation volleyed back and forth. The governor returned convicts, rebuilt stockades, and sent more troops. The miners sent the convicts off, burned the stockades, and became bolder in spite of troops. In the largest show of united force, three thousand miners throughout East Tennessee congregated at Coal Creek. They hijacked two trains, released more prisoners and burned more stockades. The governor called for additional troops and requested volunteers all over the state. The miners dug in and prepared for all-out war. But, “when the train loads of soldiers bearing field guns and Gatling guns arrived in Coal Creek they began to retreat.”7)Cotham, Perry C. 1995. Toil, Turmoil, & Triumph: A Portrait of the Tennessee Labor Movement. Franklin: Hillsboro Press.

Those who stayed fought doggedly. Troops arrested and detained miners to encourage total surrender. The fighting miners made attempts to free their fellow comrades. They seized General J. Keller Anderson while feigning surrender. The fighters’ ringleader, Bud Lindsay, pointed a gun at the general’s head and told him to surrender. Anderson “straightened himself up, threw out his arms in the face of Lindsay’s pistol and told him to ‘shoot and be damned.’”8)Daily Tobacco Leaf-Chronicle. 1892. “Coal Creek: Miners at Last Have Been Routed.” August 19. He was taken unharmed.

General Samuel Carnes was brought in to secure order and rescue Anderson. When Carnes arrested over three hundred Coal Creek citizens, some of whom were likely the miners’ family, the mineworkers surrendered and the war ended. Five hundred miners were arrested and around twenty-seven were killed. At least seven were killed on the other side. Three hundred miners were indicted for “conspiracy, for carrying arms, or for murder, but only a handful”9)Bergeron, Paul H. 1979. Paths of the Past: Tennessee, 1770-1970. Knoxville: UT Press. P 80 went to jail. The aforementioned Bud Lindsay’s detention was harrowing. Since he was the ringleader who threatened General Anderson’s life (several times), he was hanged by the neck three times and was cut down right at the point of death each time. Skirmishes emerged again in 1893 but were quickly quelled.

History may report that the Coal Creek miners’ insurrection was unsuccessful. But a closer look suggests otherwise. In 1893, the General Assembly called for the end of convict-leasing. In 1895, the leasing contracts were allowed to expire. The following year, a mere four years after the Coal Creek War, the Tennessee Legislature abolished the system for good and new prisons were built—Brushy Mountain (1896) and Tennessee State (1898).

This journey to explore Coal Creek exposed a little Tennessee city that helped change the nation and paved the way for future union organization. The mineworkers’ own futures were more uncertain. Make the trek with me next time as we explore more of Coal Creek, Tennessee.

Check out the rest of the series here:

Sources for Part 1:

- Hoskins, Katherine B. 1979. Tennessee County History Series: Anderson County. Memphis: Memphis State University Press. P 44

- Cotham, Perry C. 1995. Toil, Turmoil, & Triumph: A Portrait of the Tennessee Labor Movement. Franklin: Hillsboro Press. P 57-73

- Eller, Ronald D. 1995. Miners, Millhands, and Mountaineers: Industrialization of the Appalachian South, 1880-1930. Knoxville: UT Press. P 128

- Bergeron, Paul H. 1979. Paths of the Past: Tennessee, 1770-1970. Knoxville: UT Press. P 78

- Archbald, Hugh. 1922. The Four Hour Day in Coal. New York: H.W. Wilson Company. P 29 pdf.

- Husband, Joseph. 1911. A Year in a Coal-Mine. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. P 24 Ebook.pdf.

- Daily Tobacco Leaf-Chronicle. 1892. “Coal Creek: Miners at Last Have Been Routed.” August 19.pdf.

- Bruffey, E. C. 1892. “Lives Were Lost: And Blood Was Spilled to Save Tennessee’s Honor.” The Atlanta Constitution (1881-1945), Aug 20. pdf.

- Bruffey, E. C. 1892. “Lindsay Talks: He Tells the Story of a Day He Will Long Remember.” The Atlanta Constitution (1881-1945), Aug 23.pdf.

- COAL CREEK WATERSHED FOUNDATION, INC. (CCWF)

- Coal Creek Miners Museum

**Featured Image: Miners attacking stockade from above at Coal Creek, Tennessee – Harper’s Weekly (August 1892), Tennessee Virtual Archive, Wikimedia, pub dom

References

| ↑1 | Archbald, Hugh. 1922. The Four Hour Day in Coal. New York: H.W. Wilson Company. P 29 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Husband, Joseph. 1911. A Year in a Coal-Mine. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. P 24 |

| ↑3, ↑4, ↑5, ↑6, ↑7 | Cotham, Perry C. 1995. Toil, Turmoil, & Triumph: A Portrait of the Tennessee Labor Movement. Franklin: Hillsboro Press. |

| ↑8 | Daily Tobacco Leaf-Chronicle. 1892. “Coal Creek: Miners at Last Have Been Routed.” August 19. |

| ↑9 | Bergeron, Paul H. 1979. Paths of the Past: Tennessee, 1770-1970. Knoxville: UT Press. P 80 |

I went back and revisited the Coal Creek story. I am always impressed with your ability to intertwine history, personal experience and meaningful reflections. I also appreciate and am impressed with your notations, footnotes and great photographs. Your narratives are beautiful tributes to Appalachian/Tennessee history. Thank you.

Thank you, Peg. You have no idea how much your words mean to me. You have been with us every step of this journey, in spirit and in presence. I’m so glad you continue to enjoy our labor of love.