We’ve come to the third and final post in a series about the Extraordinary Tanner family (See posts one and two.). Today, we’ll meet the trailblazing, tenacious Tanner women, who were exceptionally intelligent and highly successful in a time when women, especially African American women, weren’t afforded serious education or recognition or titles. Join me as I introduce:

Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson

Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson was born October 17, 1864 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She married twice. Her first marriage occurred in 1886 to New Jersey native,1)Hound, Catahoula. “Dr Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson.” Find A Grave. May 27, 2012. (accessed Jan 2021). Charles Dillon. Unfortunately, Charles died unexpectedly after their daughter was born, leaving Halle a widow.2)Several sources record his death as being “unknown.” I was curious so I did a little research. I found a listing for Charles Dillon in the United States Record of Union Veterans and their burials (Family Search). Their records show he served in the Civil War as a Union Private in Co. H., Reg. 11, died January 9, 1889, and was buried in Princeton, New Jersey. I also found a listing for an African American man from New Jersey named Charles Dillon, 44 years old, in Philadelphia’s 1889 death register (Family Search), who died of gangrene. After his death, Halle moved back with her parents and assisted her father on the Christian Recorder, an African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) newspaper.

She entered the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania at the ripe, “old” age of 24, as the only African American woman in a class of 36 students.3)Black Past. “Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson.” Black Past. n.d. Broken Link ?? (accessed Jan 2021). She graduated with honors on May 7, 1891. At the time, Booker T. Washington needed a physician at the Tuskegee Institute, so, he wrote a letter to the medical college’s dean, Clara Marshall,4)Wright, A.J. “Halle Tanner Dillon.” Encyclopedia of Alabama. May 18, 2017. (accessed Jan 2021). for a recommendation. The dean informed Halle, who took the offer, then made a beeline for the Institute.

She was to be paid $600 a year, including meals, a place to stay, and a one month vacation.5)USA.gov – U.S. National Library of Medicine. “Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson.” Changing the face of Medicine. Oct 14, 2003. (accessed Jan 2021). But – she had to pass the Alabama State Medical Examination, a grueling written exam made up of ten subjects, lasting ten days. Booker T. Washington arranged a tutor, his former classmate,6)Wright, A.J. “Halle Tanner Dillon.” Encyclopedia of Alabama. May 18, 2017. (accessed Jan 2021). Cornelius Nathaniel Dorsette, “the first licensed African-American physician” in Montgomery.7)USA.gov – U.S. National Library of Medicine. “Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson.” Changing the face of Medicine. Oct 14, 2003. (accessed Jan 2021). That she took the exam caused a bit of public outrage. Undaunted, she passed the exam with a score of 78.8,8)Mosby, Dewey F. Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia: Rizzoli, 1991. becoming the first African American woman – and the first woman, period – to practice medicine in Alabama.

When she entered Tuskegee, she blazed an unstoppable trail. She cared for almost 500 persons at the college, created a nurses’ training school, formed a pharmacy for the indigent named Lafayette Dispensary, and taught two classes per day.9)USA.gov – U.S. National Library of Medicine. “Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson.” Changing the face of Medicine. Oct 14, 2003. (accessed Jan 2021). She met a fellow teacher and A.M.E. minister at Tuskegee, John Quincy Johnson. She left the Institute and married him in 1894. The couple had at least three sons.10)Mosby, Dewey F. Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia: Rizzoli, 1991. After her marriage, the Johnson family frequently moved for his career, finally settling in Nashville, Tennessee, where she continued her medical practice.11)USA.gov – U.S. National Library of Medicine. “Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson.” Changing the face of Medicine. Oct 14, 2003. (accessed Jan 2021). Sadly, Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson died on April 26, 1901 from dysentery and childbirth complications.12)Wright, A.J. “Halle Tanner Dillon.” Encyclopedia of Alabama. May 18, 2017. (accessed Jan 2021). She was 36 years old.

Isabella Tanner-Temple

Isabella Tanner-Temple was born sometime in 1867 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The little information I found adds volumes to the collective Tanner intellectualism and tireless devotion to others. She married Reverend Noah Temple and was very involved with the A.M.E. church.13)Mosby, Dewey F. Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia: Rizzoli, 1991. She was quite active in the church’s religious and educational work.14)Mathews, Marcia M. Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969. She wrote the Missionary Index and Hand Book, dedicated to “the Auxiliaries Conference Branches, and to Mite Missionary Workers” in the A.M.E. Church. She was at one time the president of the Pittsburgh branch of the Women’s Mite Missionary Society.15)African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church. Minutes of the Sixteenth Annual Session of the Women’s Mite Missionary Society Pittsburgh Conference Branch. Pittsburgh: Missionary Trumpeter, 1912. Her death date is unknown.

Mary Louise Tanner Mossell

Mary Louise Tanner Mossell was born in 1865 or 1866. She married a lawyer named Aaron Mossell from Lockport, New York. He was the first African American graduate of Pennsylvania Law School. He abandoned Mary sometime after the birth of daughter Sarah “Sadie” Tanner Mossell and moved to Cardiff, Wales.16)Mosby, Dewey F. Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia: Rizzoli, 1991.

According to her daughter, Sadie, Mary never recovered from her husband’s desertion and the stigma was too much to bear. She subsequently suffered from depression and relatives sometimes cared for her children.17)Black Past. “Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander.” Black Past. n.d. Broken Link ?? (accessed Jan 2021).

Mary wrote many letters to her brother, Henry Ossawa Tanner, updating him on the family and revealing elements of her fragile health. Mary Louise Tanner Mossell passed away “suddenly but peacefully” March 22, 1934.18)Harrison, Sadie D. “Henry Ossawa Tanner Correspondence.” Smithsonian Institution Transcription Center. Mar 22, 1934.

Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander

Mary’s daughter, Sarah “Sadie” Tanner Mossell was born January 2, 1898 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Though she wasn’t technically born in Appalachia, her story is a remarkable addition to the Tanner family legacy.

Sadie attended the University of Pennsylvania and graduated in 1918. Her college experience was rife with racism – not necessarily overt; they just didn’t acknowledge her existence. Of this time, she said, “Not one woman in my class spoke to me in class or when I passed one or more than one woman on the walks to College Hall or the library.”19)Epperson, Lia B. Knocking Down Doors: The Trailblazing Life of Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, Pennsylvania’s First Black Woman Lawyer. Paper, Women’s Legal History of Stanford, 1998. She was not, however, a woman who shrank from challenges. She continued her education, attending Graduate School at the very same university, earning a Ph.D. in economics in 1921 – the first African American woman in the nation to earn a Ph.D.20)C., Terry. “Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander.” Find A Grave. Dec 3, 2006. (accessed Feb 2021). Unfortunately, after she graduated, she couldn’t find work because “every company refused to hire an African American woman.”21)Epperson, Lia B. Knocking Down Doors: The Trailblazing Life of Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, Pennsylvania’s First Black Woman Lawyer. Paper, Women’s Legal History of Stanford, 1998. She eventually found a job with the black-owned North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company in Durham, North Carolina.22)C., Terry. “Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander.” Find A Grave. Dec 3, 2006. (accessed Feb 2021).

In 1923, she married Raymond Pace Alexander23)Alexander has an incredible story as well. He was born in Philadelphia, the son of former slaves, and, due to the unfortunate death of his mother and his father’s inability to care for the Alexander children, Raymond supported himself at 12 years old as a newspaper boy, railroad worker, and stage actor/singer/dancer. He attended the University of Pennsylvania, the Wharton School, and Harvard Law School. He was a fierce civil rights lawyer and advocate and was involved in several high-profile cases like the Trenton Six. Through his talent, hard work, and determination, he later became a judge. He was the first African American elected to the Court of Common Pleas. – Find-A-Grave, Wikipedia, Black Past, Penn Today He became a highly successful lawyer with his own practice.24)C., Terry. “Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander.” Find A Grave. Dec 3, 2006. (accessed Feb 2021). The housewife existence didn’t agree with Sadie. Raymond sensed she wasn’t happy and, when they discussed the matter, she told him she wanted to go to law school. In 1924, she attended the University of Pennsylvania Law School. The dean, Edward Mikell,25)Epperson, Lia B. Knocking Down Doors: The Trailblazing Life of Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, Pennsylvania’s First Black Woman Lawyer. Paper, Women’s Legal History of Stanford, 1998. was very racist and sexist. She said of him:

He directed that under no circumstances was I to be admitted to the club formed by a handful of women who attended the school at the time. It was after our admittance to the bar that the women told me of the dean’s feelings. I was treated either with indifference or with disdain, so I would go home directly at twelve noon when classes were over and study alone until about six p.m. No one invited me to lunch – neither women nor men, so I just adapted myself to what was.26)Epperson, Lia B. Knocking Down Doors: The Trailblazing Life of Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, Pennsylvania’s First Black Woman Lawyer. Paper, Women’s Legal History of Stanford, 1998.

She subsequently graduated and became the “first black woman admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar in 1927.”27)C., Terry. “Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander.” Find A Grave. Dec 3, 2006. (accessed Feb 2021). After graduating, she and her husband practiced law together “specializing in estate and family law.”28)C., Terry. “Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander.” Find A Grave. Dec 3, 2006. (accessed Feb 2021). They were fierce civil rights activists and advocates.

Sadie was highly successful and her life was full of firsts and notables. She was twice appointed as Philadelphia’s Assistant City Solicitor. She served on President Truman’s Committee on Human Rights (1947) and co-authored a report for a national civil rights policy entitled, “To Secure These Rights.”29)Lewis, Femi. “Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander.” ThoughtCo. Aug 11, 2018. (accessed Feb 2021 ). Sadie served on Philadelphia’s Commission of Human Relations for approximately sixteen years (1952-1968); and, in 1963, she was President of John F. Kennedy Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. President Jimmy Carter appointed her chair of the White House Conference on Aging in 1979. She was also on the board of the National Urban League for about 25 years.30)C., Terry. “Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander.” Find A Grave. Dec 3, 2006. (accessed Feb 2021).

Sadie died November 1, 1989 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She was 91 years old. Michael D’Onofrio, Staff Writer for The Philadelphia Tribune, wrote a 2018 article about a proposal to erect a statue in Sadie’s honor. In the article, he interviewed one of her mentees, Thelma Daley, who said of her, “what came out were her actions and her voice. She was the essence of resistance and the essence of persistence and the essence of excellence.”

![]()

What a wonderful, brilliant, and extraordinary family. They ministered to a hurting people, gave the world beauty and literature,31)Rt. Rev M. B. Salter, D.D. The Seven Kingdoms: A Book of Travel, History, Information and Entertainment. Philadelphia: A.M.E. Publishing House, 1902. assisted and cured the sick, fed and clothed the hungry, represented those who needed justice, and advocated for the powerless. Time and again, through generations. The entire family lived, walked, and breathed their faith, which was, arguably, most important to them. Bishop L. J. Coppin says of the Tanners in his book Unwritten History: “It is conceded by all who know the Tanner family, that it consists of an unusual set of children altogether, with one towering as an international character. They entered the Church in childhood, from a Christian home, characterized by the simple life . . . it is about what the Scripture prescribes, and reason suggests.” What a distinguishing legacy for Benjamin Tucker Tanner and Sarah Elizabeth Tanner.

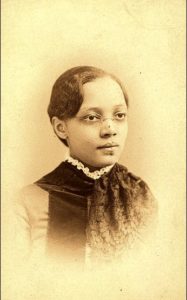

Featured Image:

- Halle Tanner Johnson, 1902 from Evidences of Progress Among Colored People by G. F. Richings – Wikimedia

- Mary Louise Tanner Mossell, 1885, by Frederick Gutekunst – University of Pennsylvania

- Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, Chief Crystal Files

References

| ↑1 | Hound, Catahoula. “Dr Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson.” Find A Grave. May 27, 2012. (accessed Jan 2021). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Several sources record his death as being “unknown.” I was curious so I did a little research. I found a listing for Charles Dillon in the United States Record of Union Veterans and their burials (Family Search). Their records show he served in the Civil War as a Union Private in Co. H., Reg. 11, died January 9, 1889, and was buried in Princeton, New Jersey. I also found a listing for an African American man from New Jersey named Charles Dillon, 44 years old, in Philadelphia’s 1889 death register (Family Search), who died of gangrene. |

| ↑3 | Black Past. “Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson.” Black Past. n.d. Broken Link ?? (accessed Jan 2021). |

| ↑4, ↑6, ↑12 | Wright, A.J. “Halle Tanner Dillon.” Encyclopedia of Alabama. May 18, 2017. (accessed Jan 2021). |

| ↑5, ↑7, ↑9, ↑11 | USA.gov – U.S. National Library of Medicine. “Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson.” Changing the face of Medicine. Oct 14, 2003. (accessed Jan 2021). |

| ↑8, ↑10, ↑13, ↑16 | Mosby, Dewey F. Henry Ossawa Tanner. Philadelphia: Rizzoli, 1991. |

| ↑14 | Mathews, Marcia M. Henry Ossawa Tanner: American Artist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969. |

| ↑15 | African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church. Minutes of the Sixteenth Annual Session of the Women’s Mite Missionary Society Pittsburgh Conference Branch. Pittsburgh: Missionary Trumpeter, 1912. |

| ↑17 | Black Past. “Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander.” Black Past. n.d. Broken Link ?? (accessed Jan 2021). |

| ↑18 | Harrison, Sadie D. “Henry Ossawa Tanner Correspondence.” Smithsonian Institution Transcription Center. Mar 22, 1934. |

| ↑19, ↑21, ↑25, ↑26 | Epperson, Lia B. Knocking Down Doors: The Trailblazing Life of Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, Pennsylvania’s First Black Woman Lawyer. Paper, Women’s Legal History of Stanford, 1998. |

| ↑20, ↑22, ↑24, ↑27, ↑28, ↑30 | C., Terry. “Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander.” Find A Grave. Dec 3, 2006. (accessed Feb 2021). |

| ↑23 | Alexander has an incredible story as well. He was born in Philadelphia, the son of former slaves, and, due to the unfortunate death of his mother and his father’s inability to care for the Alexander children, Raymond supported himself at 12 years old as a newspaper boy, railroad worker, and stage actor/singer/dancer. He attended the University of Pennsylvania, the Wharton School, and Harvard Law School. He was a fierce civil rights lawyer and advocate and was involved in several high-profile cases like the Trenton Six. Through his talent, hard work, and determination, he later became a judge. He was the first African American elected to the Court of Common Pleas. – Find-A-Grave, Wikipedia, Black Past, Penn Today |

| ↑29 | Lewis, Femi. “Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander.” ThoughtCo. Aug 11, 2018. (accessed Feb 2021 ). |

| ↑31 | Rt. Rev M. B. Salter, D.D. The Seven Kingdoms: A Book of Travel, History, Information and Entertainment. Philadelphia: A.M.E. Publishing House, 1902. |

Are any of Halle Tanner Johnson descendants living today.What became of her husband ,children,grandchildren,great grands etc

Hello Dinah. (Please excuse the chaos from the links.) I’ve been doing a little more digging for an answer to your questions. I ran into a tough road finding information after Halle Tanner Johnson’s death. Unfortunately, some records regarding African Americans are sparse and difficult to obtain. I found it hard to verify the information I did find, but here goes: John Q. Johnson was president of Allen University for about one year. I also saw where he was a Reverend for the Mt. Pisgah AME Church. I think (note the middle name) I found information on one son, Benjamin Tanner Johnson. He attended Howard University and Harvard Business School. His letters are found at Harvard Library, and only seem available onsite, but the descriptions offer a few elements of his life: He had a wife, Effie, and at least one son. Additionally, the Harvard Business School website offers another bit of information: He supported and fought for African American owned banks. He was a WPA supervisor for Connecticut; he taught at Howard University; and he was an executive secretary for Canton Ohio’s Urban League. The site offers images (though not of his person) – a newspaper clipping, a building of the People’s Finance Corporation (which he founded), and a letter he sent to W.E.B. Dubois requesting support for African American businesses. I know it’s just a fraction of information but I hope that answers some of your questions. The Tanner history is wonderfully fascinating. I originally sought to write about Henry Ossawa Tanner, but, once I started researching, I was blown away by the entire family. I enjoyed learning about them and was glad to share what I found. Here are links I used:

https://www.onecolumbiasc.com/organization/allen-university/

https://sites.google.com/site/mtpisgahameprinceton/home/history-of-mt-pisgah-ame-church

https://hollisarchives.lib.harvard.edu/repositories/11/resources/631/collection_organization

https://www.library.hbs.edu/hc/AASU/the-golden-age-of-black-business/