The historical significance of sub-cultural music is dynamic. The importance of music as a generalization directly affects the health of a growing society, for we are all inspired and impacted by its power on a daily basis. Understanding where the nuances of a musical genre come from opens our possibilities for future evolution in art and media. To allow some of the more obscure factions of our American heritage to disappear from history is a tragedy. Documentation and historical reference are what keeps American art and entertainment diverse and alive.

What has come to be known as traditional Appalachian music is a fusion of sounds created by several different groups of immigrants and slaves moving through the eastern United States from the 1700s on through the early 1900s.

There are scattered references of “Appalachian” and “Mountain” music that have crept into the descriptions of various genres, generally with the agenda of creating a longing for a long-lost lifestyle. These words only entered the musical arena a little over a hundred years ago. These descriptions are meant to invoke an emotional impulse that categorizes this unique style of folk music and sets it apart from folk rock, or location-based folk styles, such as Celtic, European, or even Cajun.

Appalachian pioneers were a significantly unparalleled group of settlers in America. They were a mix of groups, primarily consisting of economic minorities, runaway slaves, and family “clans” who hid in the mountains to evade authorities. Interestingly enough, a great many white men and their families were brought to the new world by ship as a form of punishment after being found guilty of crimes against legal institutions of Great Britain. Once in America, escape routes were relatively easy, and the Appalachian Mountain range provided very good camouflage. The time frame of this occurrence dates around the 1760s.

This period is significant, because it led to a culture change that would have a major impact on music. In addition to white men leaving their wives and children in an effort to hide from the law, this was a time of runaway slaves traveling up from the Southeastern United States. It became common for abandoned women and children to pair up with slaves on the run in support of each other’s survival in a tangled thicket of unforgiving territory. Many Native Americans entered the mix as well, producing a tri-racial population documented as the Melungeon people, who took up a substantial space in Southern Appalachia. Of course, no records exist revealing how these intimate relationships occurred, although common-sense bears a strong explanation, especially considering the generational bloodlines in the area and the passing down of oral stories in those families.

Now we come to an era of the fusion of music from old European folk ballads, slave and gospel tunes, and rhythmic spirituality of Native American music. Africans passed their crafting of instruments to European settlers, and the banjo and dulcimer became a staple of what would later be referred to as Appalachian music and Bluegrass. The first scholarly dissertation of the subject of Appalachian music came from Bill C. Malone, and was categorized as “American Country Music.” His paper was published in 1968. The cause and effect of this was a larger discovery of the lesser-known music of the southeastern mountains and its people.

The musical compositions often touched on topics of murder, illicit love, and violence, but as with all music, society excuses these more questionable things when channeled into song. This is the magic of music. This isn’t so farfetched, as most European folk ballads speak of tragic tales as well. Some reach as far back as the 1300s with songs like the original “House Carpenter,” which told the tale of a woman leaving her husband and baby to board a “gallant ship” with another man who we find out at the end is a demon, taking her to Hell with him.

These musical stories were a great fit with an environment of eclectic storytellers, historic feuds, and moonshiners. Eventually, this would find its way into American film with budget horror movies and the writers of chiller novels. American horror has historically been unkind to Appalachia, although some of the first creations were actually based in fact. There have been notorious true horrific happenings in the dark woods of these southern pines.

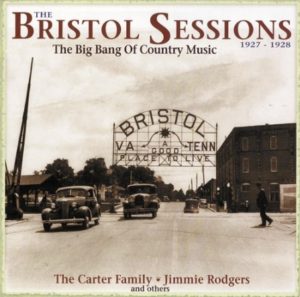

Aside from Hollywood blockbusters and books designed to question a camping trip to Virginia, Appalachia produced renowned musicians who inspired some of the most iconic music in America. In 1927, the Victor Talking Machine held a series of recording sessions in Bristol, Tennessee, giving legs to one of the first commercial sessions that would become a notable event repeating itself even today with an anniversary project called the Bristol Sessions. This led to a resurgence of folk “revival” music in the 30s and 40s that would produce iconic musicians such as Clarence Ashley, Dock Boggs and Roscoe Holcomb, Mike Seeger and John Cohen would later travel to remote areas of the Appalachians to produce field recordings. Dolly Parton, Ricky Skaggs, and Dwight Yoakam brought back the Appalachian sound to more modern country music in the 1980s. One of the most popular North Carolina tragedy ballads was the “Legend of Tom Dula (Dooley),” which hit the number one spot on US music charts in 1958 after being performed by the Kingston Trio. The legend is based on the true story of a murderous love triangle.

In conclusion, Appalachian folklore and music has had a huge impact on American culture. It was the basis of what later became country music, and it has spawned entire improvisational bluegrass festivals, connecting even more music and people together with fusions of rock and even Spanish influence. Presently, the term “Appalachian music” has broadened to include so much diversity that it’s hard to pin down an actual, identifiable sound. But that’s the beauty of it; Appalachian music was always meant to be diverse. It’s a melting pot of music, like America is a melting pot of ethnicity. And in that, Appalachian music is one of the strongest art forms, giving a real foundation to the cultural roots of America.

I’m Christine Greyson, an Appalachian musician and independent author based in Wilkesboro, North Carolina. My passion is music, and I grew up in a strong Appalachian music-based family. I am kin to Stanley Hicks, one of the first nationally known banjo and dulcimer makers in US history. My mother was a folk singer, and has an album in an Appalachian folk collection of Folkways Recordings at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC. I created a solo podcast during the Covid pandemic called Natural and Wild with Christine Greyson — it’s nonprofit and ran the course of the pandemic era.

I really just want to spread the history of Appalachian music. I find it interesting, and I believe it’s a very misunderstood subject and culture.

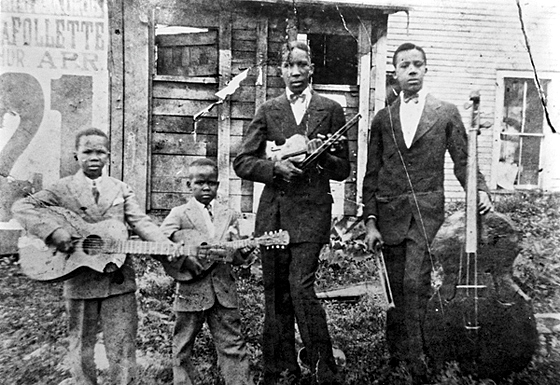

Featured image: 1935 Maynardville, TN musicians – Ben Shahn, photog., Farm Security Administration – Wikimedia