A person cannot live in Appalachia or the South without experiencing “hillbilly music,” replaced in 1949 as “country music.” The familiar sonority, accompanied by a melodic, twangy dialect, echoes and reverberates across hills and hollers, flat lands and swamps. It surrounds just about every facet of the region and can be sung in such genres as ballads and hymns or blues and bluegrass.

Ken Burns’ series, Country Music, presents a window into the American-born music and begs us to pull back the curtain and recognize the “emotional archaeology” of “an almost indescribably wise past.” It revolves around talents and stories. But, as you will read, the series also leaves room to question little addressed issues.

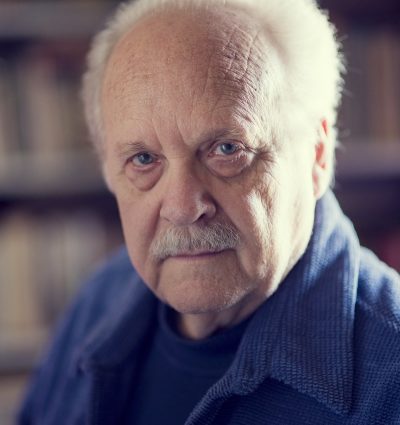

Two-time Pulitzer Prize nominee, David Madden, renowned author of over fourteen novels, sixty short stories, and sixty poems; award-winning playwright, biographer, editor, and Civil War historian, presents the series’ crucial oversight in his comments below.

Ken Burns deserves, generally, to be regarded as a unique national treasure.

But his documentaries, even his best, are too long, in various ways somewhat flawed, and his eight-part, 16-hours-long Country Music is a major example of that.

Given the fact that the history of country music is the story of white Southerners during decades of racism, voter suppression, Jim Crow daily torment, and lynchings in the South, Burns’ repeated claims, mechanically interjected, that the music of African Americans played a role in the development of country music is disrespectful exploitation, verging on condescension. If there is historical truth in that claim, too little proof is in the series. He merely alludes to, more than he makes convincingly clear, the role of African American musicians in country music.

And given the general context of white musicians and their audience delineated in the series, he gives the impression that white music meant to African Americans, called Negroes in the early decades, much the same as it did to them, somewhat slighting the basic role of blues and jazz.

Repeatedly, almost verbatim, in the same sentimentally awed tone, singers and others declare in interviews that country music is “the story of my people,” or “my story,” and some such. Given the fact that Burns inserts images and comments by African Americans, the implication that it is also their story made me distinctly uncomfortable, made me imagine how they, watching perhaps, might feel about that.

One other observation, minor by comparison, has to do with Peter Coyote, one of my favorite actors. His voice is distinctive, very effective for narrating documentaries. In this one it becomes monotonous and tedious; its somewhat mournful tone and rhythm is not at all suited to the legacy of country music, especially in contrast to the celebratory enthusiasm of the singers and other persons interviewed.

**Photo source: David Madden/ Photographer – Blake Madden