Growing up in the 1960s during an era of assassinations, civil unrest, and the war in southeast Asia, at times I wore sadness like a raincoat as a palpable and threatening cloud hung over the nation. My memories of that time recur as a series of stock and binary images: white state troopers beating, tear gassing and siccing dogs on peaceful black protesters seeking expansion of voting rights in Selma, Alabama; pugilistic white Alabama governor George Wallace blocking the door to keep Blacks from enrolling at the University of Alabama in 1963; and Ruby Bridges, only six years old in 1960 when she became the first African American child to integrate an all-white school in New Orleans despite daily taunts, cursings, and death threats.

Maybe black and white TV magnified these dualities as children learned, without being told, that the cowboy wearing a white hat was the good guy; the cowboy wearing the black hat was the bad guy. It was subtle, perhaps unconscious, reinforcement of an archetype: white is good; black is evil. If the intent of these polarities was to instill ingrained habits of thought, that strategy produced the opposite impulse in me. Nor do I presume to be the only child who heard and saw what he wasn’t supposed to hear or see or whose sensibility was shaped by a curious illogic and a perverse rejection of facile and self-serving “truths.” “We hold these truths to be self-evident” was not evident to me. Seeking truth was an existential challenge inevitably exposing contradictions not easily resolved.

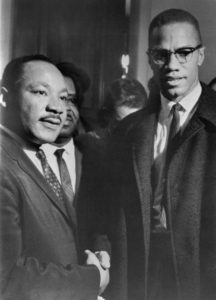

To my thinking at the time, the responses to racist brutality and violence distilled in the contradictory stances of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. King’s teachings isolated the triple evils of Poverty, Racism, and Militarism, an intersectionality that prompted the activist to formulate principles of non-violent resistance to evil. His philosophy emphasized love over hate and held that suffering could educate and transform. Malcolm X’s militancy was expressed in the following quotation: “If someone puts their hands on you, make sure they never put their hands on anyone else again.” Malcom X grasped a fundamental tenet of human nature: Bullies rarely cease being bullies of their own accord. They need convincing by whatever means necessary.

To my thinking at the time, the responses to racist brutality and violence distilled in the contradictory stances of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. King’s teachings isolated the triple evils of Poverty, Racism, and Militarism, an intersectionality that prompted the activist to formulate principles of non-violent resistance to evil. His philosophy emphasized love over hate and held that suffering could educate and transform. Malcolm X’s militancy was expressed in the following quotation: “If someone puts their hands on you, make sure they never put their hands on anyone else again.” Malcom X grasped a fundamental tenet of human nature: Bullies rarely cease being bullies of their own accord. They need convincing by whatever means necessary.

All my life I’ve ricocheted between these extremes. I’m not a pacific person by nature but believe peace preferable to the alternative. I’ve participated in peaceful protests but never felt the urgency of violence that Malcolm X deemed necessary at times. I’d be remiss if I failed to note some similarities between King and Malcolm X. Both were jailed. While behind bars, King famously wrote “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” addressed to white pastors in the city. While incarcerated in prison, Malcolm X (1946, Massachusetts State Prison) learned to read by memorizing the dictionary, recognizing the nascent power in literacy. Both men were murdered for their causes, leading me to wonder what it is about American racism requiring a Black man to be imprisoned or murdered before change is enacted into law. That has been a pattern throughout our country’s history. As there seems to be no middle ground, my decades-long question remains: Which man’s approach – King’s or Malcolm X’s – was more nearly correct?

Let’s pose that question concerning George Floyd’s murder. Floyd didn’t resist arrest, despite official lies that he did. He submitted to handcuffs and was forced to the ground. Even while being tortured, he begged for his life – politely – until his last anguished gasp. Martin Luther King would say George Floyd died a martyr for change. Malcolm X would say his death was a flash point for revolution and overthrow of sinister institutions.

Between these extremes we reside – in smoke and flames, architects of a hell we created, an inferno whose inhabitants shriek in decibels drowning out every sound but one unheeded inconsolable plea:

“I can’t breathe!”

**Featured Image: George Floyd Protest – Flicker – zot0 (Mike K)

View some of the visual accounts below:

1958 - Battle of Hayes Pond - State Archives of North Carolina. After the ruling to end segregation, the KKK tried to reassemble in North Carolina. One of their targets was the Lumbee Native American Tribe. One hundred Klan members formed a rally, intending to terrorize the Lumbee. But 500 Lumbee tribesmen waited and surrounded the Klan and drove them out.

1989 - The Central Park Five (not sure about the order: Anton McCray, 15; Kevin Richardson, 15; Yusef Salaam, 15; Raymond Santana, 14; Korey Wise, 16) were falsely accused of the brutal rape of a Central Park jogger and subsequently coerced into confessions with no guardian or lawyer present, even though they were all minors. The woman wasn't expected to survive, but she did and had no memory of the attack. At trial, they each declared not guilty, but were convicted, however, and, after serving several years in prison, DNA evidence pointed to Matias Reyes as the lone rapist. The Central Park Five were exonerated and charges were vacated. They also received a $41 million settlement. In May of 1989, Donald Trump placed a one-page ad in the New York Daily News against the Central Park Five with a headline that read: "Bring Back the Death Penalty. Bring Back Our Police!" saying, in part, they were "wild criminals" and "crazed misfits" who "should be forced to suffer" and "be executed for their crimes." Imagine if that had happened to these five innocent young men./ Sources: The History Channel and The Guardian

2010 - Anastasio Hernandez Rojas was in the custody of U.S. federal agents and Border Patrol when one of the agents allegedly injured him, and he wanted to file a complaint. Instead, an agent took him to the border where at least a dozen agents beat (causing broken ribs, loose and broken teeth, bruises, and an injured spine) and tased him. He died in the hospital. The U.S. Justice Department shut the case with no charges.