When someone reflects on Women’s suffrage in the United States, that person might recognize women like Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, or Alice Paul. Here in Appalachia, however, we had our own heroine who worked tirelessly for women’s rights and issues. This Women’s History Month, Appalachia Bare is recognizing her.

Lizzie Crozier French was born in Knoxville, Tennessee, on May 7, 1851 to John H. Crozier and Mary Williams Crozier.1)DeFiore, Jane Crumpler. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Tennessee Encyclopedia. Oct 8, 2017. John was a staunch Whig back in the day. He served in both the Tennessee House of Representatives (1837-1839) and the United States House of Representatives (1845-1849).2)DeFiore, Jane Crumpler. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Tennessee Encyclopedia. Oct 8, 2017.3)Cloudfront. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Cloudfront. Unknown. (accessed Jan 2021). The Whig party was known to center policies on economic growth, until the mid-1850s when the party fractured over the issue of slavery. In the lead-up to the Civil War, slavery (and the human lives thereof) was an economic pawn, especially for increased territories that vied for the right to cash-in on this precious “commodity.” The Whigs had a problem, however. Some of the party agreed with the Missouri Compromise4)The Missouri Compromise set a precedent by barring slavery “in the Louisiana Territory north of the 36° 30´ latitude line.” while others successfully overturned it with the Kansas-Nebraska Act.5)The Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed new territories the right to decide for themselves whether slavery would be permitted. The party fractured. In 1854, the anti-slavery faction broke from the party and became the Republicans, while the pro-slavery faction remained the Whigs. Well, as stated before, John Crozier was a staunch Whig, and, as one might guess, sympathized with the Confederates. Yet, in the state of Tennessee, the eastern portion where the Croziers dwelled was a Union focal point – a hornet’s nest for a Confederate sympathizer. Accordingly, John and his family to move from the state until after the war.

All that backstory told; we return to our heroine. As a result of the move, Lizzie was able to attend school at the Convent of the Visitation in Georgetown (Washington D.C.) and an Episcopal association for women in Columbia.6)DeFiore, Jane Crumpler. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Tennessee Encyclopedia. Oct 8, 2017. She married William Baxter French, “the cashier of the wholesaling giant Cowan, McClung and Company,”7)Cloudfront. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Cloudfront. Unknown. (accessed Jan 2021). and they had a son, William Williams French.8)Odd name combination, to be sure, but it was quite common for a child’s middle name to be a grandmother’s maiden name. Just like today, it was certainly common to name a son after his father, particularly the first name, if not as a “junior” altogether. To me, the oddity of “William Williams” seems an act of defiance. Since genealogy centers mainly on the male surname, it seems Lizzie wanted to ensure the female lineage was represented.9)Taylor, Jannis F. “Biographical Sketch of Margaret Elizabeth Crozier French.” Alexander Street, Biographical Database of National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1890-1920. Unknown. (accessed Feb 2021).10)Geni Private User. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Geni. Sept 12, 2020. (accessed Jan 2021). Sadly, her husband died about 1½ years after their marriage11)DeFiore, Jane Crumpler. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Tennessee Encyclopedia. Oct 8, 2017. and she never remarried. Instead, she devoted her life to women’s rights and issues.

I wish I could stand here today and say “Fellow Citizens” but since I’m not recognized as a fellow citizen I must say citizens and fellow servants.12)James, Paul. “The Formidable Lizzie Crozier French.” City of Lifestyle, Knoxville. Unknown. (accessed Feb 2021). —Lizzie Crozier French

In the late 1880s, Crozier French began her life as an unstoppable whirlwind for women’s causes. At the time, colleges excluded women so, with her sisters, Lucy Graham Crozier and Mary Hume Crozier, on board, Lizzie opened the East Tennessee Female Institute,13)DeFiore, Jane Crumpler. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Tennessee Encyclopedia. Oct 8, 2017. (also called the Knoxville Female Academy) a “private school” that educated women.14)James, Paul. “The Formidable Lizzie Crozier French.” City of Lifestyle, Knoxville. Unknown. (accessed Feb 2021). She wrote and published a Manual of Elocution that was “used as a textbook in the school’s public speaking classes.”15)Blues, Evening. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Find A Grave. Jan 14, 2004. (accessed Jan 2021). In November 1885, she founded the Ossoli Circle, the first women’s club in Tennessee. The name “Ossoli” was chosen to honor feminist and transcendentalist, Margaret Fuller Ossoli, and its purpose was “to form a literary society intended to advance [women’s] intellectual and moral development . . .” The Circle implemented “traveling libraries,” assisted mountain schools, argued on women’s behalf for changes in law, and created a girls’ vocational school.16)Gaston, Kay baker. “Ossoli Circle.” Tennessee Encyclopedia. Mar 1, 2018. (accessed Feb 2021). As a woman who refused to compromise on certain issues, Lizzie zealously pushed the University of Tennessee, Knoxville to be a coed university.17)James, Paul. “The Formidable Lizzie Crozier French.” City of Lifestyle, Knoxville. Unknown. (accessed Feb 2021). Consequently, the university became coeducational in 1892.

Crozier French took up the cause of women’s rights. Part of that issue involved women’s labor and subsistence,18)DeFiore, Jane Crumpler. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Tennessee Encyclopedia. Oct 8, 2017. particularly women who could no longer work.19)Taylor, Jannis F. “Biographical Sketch of Margaret Elizabeth Crozier French.” Alexander Street, Biographical Database of National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1890-1920. Unknown. (accessed Feb 2021). In the 1890s, she formed the Woman’s Educational and Industrial Union20)DeFiore, Jane Crumpler. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Tennessee Encyclopedia. Oct 8, 2017. and helped create the Mount Rest Home for elderly women.21)James, Paul. “The Formidable Lizzie Crozier French.” City of Lifestyle, Knoxville. Unknown. (accessed Feb 2021). She used her voice and status to fight for women’s social issues. She petitioned for a female position in the Knoxville Police Department, so “that women and children were treated differently from male criminals,” and the job was subsequently established. While on the subject of women and crime, the Lizzie Crozier French biography on Cloudfront, provides a staggering and incredulous law proposed by the city of Knoxville, Tennessee, regarding prostitutes and their customers:

In 1914, Knoxville’s city commission enacted an ordinance that essentially allowed prostitutes in parts of the city to operate without fear of arrest. Crozier French assailed the commission over this ordinance, and engaged in a back and forth with Mayor Samuel Heiskell over the city’s refusal to arrest men who hire prostitutes. During this period French began publishing a magazine, The People, the purpose of which was to expose corrupt ‘ring leaders’ running the city.

Lizzie doesn’t mince words, either, in describing exactly what kind of magazine it isn’t:

This publication claims not to be a guide to society ladies . . . You will not learn from these columns how to butter your bread or hold your fork. The best manner of folding your napkin will be left to your imagination . . . The editor of this journal takes it for granted that its readers are not inmates of institutions for the feeble minded.22)French, Lizzie Crozier. “The Lizzie Crozier French Scrapbook, 1909-1940 .” Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection. Jun 19, 2009. (accessed Feb 2021). p. 7

No need to guess – Lizzie was a huge advocate for women’s suffrage in Tennessee and the nation. She was neck-deep in titles and accolades. She organized the Knoxville Equal Suffrage Association, was president of both the Tennessee Equal Suffrage Association and the Tennessee Federation of Women’s Clubs. She was also the Tennessee chair of the National Woman’s Party. Due to her experience as a women’s labor activist, Lizzie became the first woman to speak to the Knoxville City Council and, subsequently, “the first woman to address the Tennessee State General Assembly.”23)Blues, Evening. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Find A Grave. Jan 14, 2004. (accessed Jan 2021). She was also the “first woman to address the Tennessee Bar Association,” where she gave a speech called “Address on Women’s Rights.” This speech became “one of the most quoted speeches used by Suffrage groups”24)Blues, Evening. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Find A Grave. Jan 14, 2004. (accessed Jan 2021). at the time.

If you’re going to say it at all, say it loud!25)James, Paul. “The Formidable Lizzie Crozier French.” City of Lifestyle, Knoxville. Unknown. (accessed Feb 2021). —Lizzie Crozier French

The women’s movement needed more statewide exposure to garner further support. Crozier French formed the Knoxville Writer’s Club in 1911 as an avenue for women to broadcast their suffrage support through letter-writing campaigns26)Taylor, Jannis F. “Biographical Sketch of Margaret Elizabeth Crozier French.” Alexander Street, Biographical Database of National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1890-1920. Unknown. (accessed Feb 2021). to newspaper editors across the state. She was considered one of the best public speakers in the suffragist movement at the time. Her bold, aggressive, and fearless approach was believed to be a trait inherited from her father.27)Blues, Evening. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Find A Grave. Jan 14, 2004. (accessed Jan 2021). Age never stopped her, either. At 72 years old, Lizzie ran for city council in 1923, but “narrowly” lost.28)James, Paul. “The Formidable Lizzie Crozier French.” City of Lifestyle, Knoxville. Unknown. (accessed Feb 2021).

Lizzie was sick in May of 1926, yet she attended a room dedication at Washington D.C.’s National Woman’s Party Building in her honor. She died the day after she arrived there on May 14, 1926.29)James, Paul. “The Formidable Lizzie Crozier French.” City of Lifestyle, Knoxville. Unknown. (accessed Feb 2021). Margaret Elizabeth “Lizzie” Crozier French is buried at the Old Gray Cemetery in Knoxville, Tennessee. A bronze statue titled The Tennessee Woman Suffrage Memorial by Alan LeQuire is solidly positioned on Market Square in downtown Knoxville. The effigy stands as bold as the women it honors. Lizzie Crozier French, flanked by Tennessee suffragists Anne Dallas Dudley and Elizabeth Avery Meriwether are depicted as moving forward, determined and with purpose.

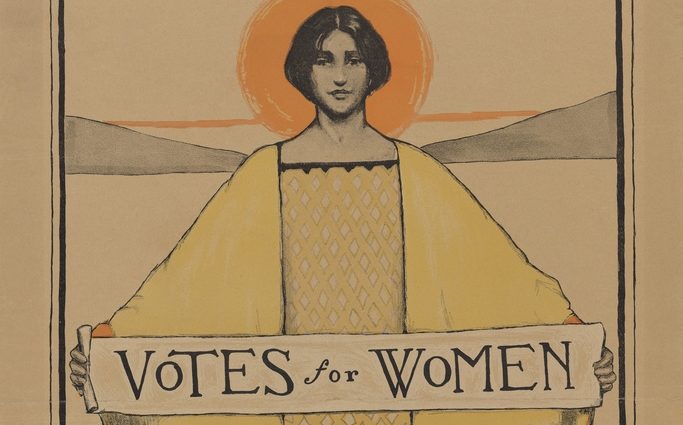

**Featured Image of suffrage poster from Schlesinger Library via Picryl

Check out the following trailers on Womans suffrage:

United States – Iron Jawed Angels

Britain – Suffragette

And a British fictional Enola Holmes:

References

| ↑1, ↑2, ↑6, ↑11, ↑13, ↑18, ↑20 | DeFiore, Jane Crumpler. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Tennessee Encyclopedia. Oct 8, 2017. |

|---|---|

| ↑3, ↑7 | Cloudfront. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Cloudfront. Unknown. (accessed Jan 2021). |

| ↑4 | The Missouri Compromise set a precedent by barring slavery “in the Louisiana Territory north of the 36° 30´ latitude line.” |

| ↑5 | The Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed new territories the right to decide for themselves whether slavery would be permitted. |

| ↑8 | Odd name combination, to be sure, but it was quite common for a child’s middle name to be a grandmother’s maiden name. Just like today, it was certainly common to name a son after his father, particularly the first name, if not as a “junior” altogether. To me, the oddity of “William Williams” seems an act of defiance. Since genealogy centers mainly on the male surname, it seems Lizzie wanted to ensure the female lineage was represented. |

| ↑9, ↑19, ↑26 | Taylor, Jannis F. “Biographical Sketch of Margaret Elizabeth Crozier French.” Alexander Street, Biographical Database of National American Woman Suffrage Association, 1890-1920. Unknown. (accessed Feb 2021). |

| ↑10 | Geni Private User. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Geni. Sept 12, 2020. (accessed Jan 2021). |

| ↑12, ↑14, ↑17, ↑21, ↑28, ↑29 | James, Paul. “The Formidable Lizzie Crozier French.” City of Lifestyle, Knoxville. Unknown. (accessed Feb 2021). |

| ↑15, ↑23, ↑24, ↑27 | Blues, Evening. “Lizzie Crozier French.” Find A Grave. Jan 14, 2004. (accessed Jan 2021). |

| ↑16 | Gaston, Kay baker. “Ossoli Circle.” Tennessee Encyclopedia. Mar 1, 2018. (accessed Feb 2021). |

| ↑22 | French, Lizzie Crozier. “The Lizzie Crozier French Scrapbook, 1909-1940 .” Calvin M. McClung Historical Collection. Jun 19, 2009. (accessed Feb 2021). p. 7 |

| ↑25 | James, Paul. “The Formidable Lizzie Crozier French.” City of Lifestyle, Knoxville. Unknown. (accessed Feb 2021). |