The rolling, rock strewn mountain forests of Southern Appalachia can be a wonderful place to experience the vast wonders of the natural world on a peaceful hike. The region is rich with bounty. Its hills, hollows, and valleys full of wild, edible plants, tasty fruits and berries, wholesome nuts, plentiful game, and deep rich soil for farming. Appalachia is also rugged and dangerous, and those who lived here before the conveniences of modern technology, both Native American and settlers, had to be independent and resourceful to survive and thrive. They had to live off the land, grow their own food, fish, hunt, and fight to feed and protect their families.

These new settlers came in search of a place where they could live and raise families and build their own communities. Once they arrived, they found numerous native tribes already established in these mountains, and a complex relationship developed between the two groups. Fierce fighting occurred, to be sure, but so did trade and cultural exchange. The frontiersman and their families learned much from the native peoples about hunting, tracking, and surviving in the Appalachian Mountains. The Scots, Irish, and Scots-Irish (or, Scotch-Irish) were among the earliest settlers who pushed through these mountains, hoping to escape a monarchy’s oppressive rule. What they experienced, however, was monarchy’s increasing presence in the “new world.” For the people who settled here, the political dissension of the northern and coastal colonies between Whigs (Patriots) and Tories (Loyalists) didn’t intrude on life very much.

What did intrude was the Treaty of Paris of 1763.1)I won’t delve too deeply into the Treaty, but, essentially, it was a peace treaty between Great Britain, France and Spain ending the Seven Years’ War (aka the French and Indian War). The accord set boundaries for the settlements in America so colonies could coexist in relative peace. I found the language restricting expansion westward, across the mountains, rather paternalistic and condescending. Whether the real intention of these restrictions was to protect the Native Americans or to maintain direct control and power over such expansion, and whether any real will existed to enforce such restrictions, is a matter of debate. Accessed: http://www.tngenweb.org/tnland/intruders/17631007.htmlThis treaty included a Royal Proclamation that restricted settlement beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains and regulated trade with the native tribes. It required anyone who already took lands there to abandon them and return to the established colonies. Therefore, any persons who stayed and traded with the native tribes did so without a license and were in violation of the King’s Law. Eventually, the Revolutionary government of North Carolina established Washington and Sullivan Counties (present day East Tennessee) in opposition to the treaty. These counties, along with Washington County, Virginia (present day eastern Kentucky and part of West Virginia), are in the very region where the Overmountain Men, who fought the Loyalists at the Battle of King’s Mountain on October 7, 1780, originated.

The Battle of King’s Mountain was a unique and pivotal battle in our nation’s fight for independence. This action was the only battle fought entirely by Americans, with the exception of the British commander, Major Patrick Ferguson, and a handful of others. It was a turning point in the Revolutionary War because it was the first decisive victory for the Americans in 1780, who had lost all the major actions in the south and were in a stalemate in the North. And it was delivered entirely by the Overmountain Men of Appalachia in the Carolina backcountry, without the support or knowledge of the Continental Army. The battle itself only lasted an hour and five minutes but the tale is much greater than that.

Our cast of characters couldn’t have been set up better by a novelist. Our Antagonist is Major Patrick Ferguson,2)His memorial lists him as a Colonel but he was a Major according to all the contemporary documents. recently appointed Inspector General of Militia by General Clinton and serving under Lord Cornwallis, who took charge of the southern forces after Clinton returned north. Ferguson was given the charge of raising a Loyalist militia with the 71st Foot to support the regular British troops. He was commanding roughly 1,100 of those men in the field, many recruited from New York and New Jersey.3)https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/10227/patrick-ferguson and https://www.britannica.com/biography/Patrick-Ferguson]

Major Ferguson was a Scottish soldier, inventor, and marksman with a distinguished military career. He was born in 1744 in Aberdeenshire, Scotland and received an officer’s commission in 1759 at the tender age of fifteen. He served briefly in the Seven Year’s War (where he took ill) and the West Indies before being sent to America in 1777.4)https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/10227/patrick-ferguson In 1776, after a long convalescence, he was awarded a patent for his Ferguson rifle. This rifle was an improved breech-loading flintlock with which “six aimed shots per minute could be fired with an accuracy creditable to any rifle. Advancing riflemen could fire four aimed shots per minute.” It could also be reloaded from a prone position, unlike any other flintlock of the time.5)Rifles and Riflemen at the Battle of Kings Mountain by National Park Service Public History Series number 12, 1941, p. 9. https://archive.org/details/riflesriflemenat12nati/page/8/mode/2up Ferguson’s rifle was first used at the Battle of Brandywine,6)Ibid. p. 10 a successful campaign for both the rifle and the British. It was limited in production with approximately 150 in service at King’s Mountain.7)Ibid, p. 15 The Battle of King’s Mountain was the last time the Ferguson Rifle was used.

We move forward now to our Protagonists – the Overmountain Men, more than a thousand rugged mountaineers with little or no formal military training, and the Continental Army which was formed by the Second Continental Congress in 1775. The mountaineers were collected and placed under the leadership of seven Colonels. Those Colonels were: Isaac Shelby (1750-1826), John Sevier (1745-1815), William Campbell (1745-1781),8)https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/9507923/william-campbell Charles McDowell (1743-1815), Andrew Hampton (1713-1815),9)https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/25237945/andrew-hampton Benjamin Cleveland (1738-1806),10)https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/cleveland-benjamin and Joseph Winston (1746-1815). Isaac Shelby became first Governor of Kentucky.11)https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/11823/isaac-shelby John Sevier would go on to be the first Governor of Tennessee.12)https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/john-sevier/ McDowell later became a Virginia state senator.13)https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/patriot_leaders_nc_charles_mcdowell.html Joseph Winston was cousin to Patrick Henry and went on to serve in the third US Congress and the North Carolina legislature.14)https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/winston-josephThese men worked together to defend their people, their region, and to fight for a newly established country.

Since the characters have been properly introduced, our story really starts in August of 1780, after the stunning defeat of the Americans under General Horatio Gates at the Battle of Camden in North Carolina. The rout at Camden was the latest in a series of American losses in the South that ultimately cost General Gates his command. The Continental Army lost valued officers and men, and both sides thought these losses indicated the British had won the South This battle was the first for the Overmountain Men and Gates lined them up against the best of Cornwallis’ forces.15)https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/camden Given their lack of military training, and, though they were well experienced at fighting in the mountains of the western frontier, they were out of their element on a traditional battlefield and were quickly overrun.

After Camden, Cornwallis turned his attention northwards to close in on the Continental Army in North Carolina. He left Maj. Ferguson and his Loyalist militia to guard his flank and manage the retreating Patriots while the Major continued to raise support.16)https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/kings-mountain The remaining leaders, the Overmountain colonels, retreated back over the mountains, with plans to raise more forces and regroup. Ferguson pursued the retreating forces into the mountains and successfully dispersed some isolated militia but failed to overtake the main groups. He made two very critical and costly mistakes. He assumed the people in the mountainous backcountry could be coerced toward loyalty to the crown, as many in the lowlands had been, and he threatened the Overmountain Men, their homes, and their families. As history has shown, such threats are not taken lightly by the people of Appalachia.

In mid-September Ferguson posted his troops at Gilbert Town, North Carolina (in current Rutherford County, N.C.), an important trading center of the time. While there, he released a prisoner, with a message for the American Overmountain Men: lay down arms and surrender, or else. The message, along with intelligence on the Loyalist forces, was delivered directly to Col. Shelby.17)King’s Mountain and its heroes: history of the Battle of King’s Mountain, October 7th, 1780, and the events which led to it. by Lyman C. Draper, published by Peter G. Thompson, Cincinnati, 1881, p.162. https://archive.org/details/cu31924032752846/page/n7/mode/2up Major Ferguson’s message was:

that if they [the Patriots] did not desist from their opposition to the British arms, and take protection under his standard, he would march his army over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay their country waste with fire and sword. 18)Quoted from Gov. (Col.) Shelby’s pamphlet published in 1823, reprinted in Draper, p. 562

The response of the Overmountain Men was, in retrospect, predictable. Shelby sent word to his fellow commanders, and on September 25th Colonels Shelby, Sevier, Campbell, and McDowell gathered their 1,140 men at Watauga and marched the next day. On September 30th they reached the Catawba River where Col. Cleveland joined them with another 350 men. The next day, October 1st, the principal leaders met in council where Col. McDowell left to reach Gen. Nathaniel Green (who replaced Gates) to request a commanding officer.19)From the Diary of militiaman Benjamin Sharp, published in the American Pioneer in Feb 1843; accessed https://www.tngenweb.org/revwar/kingsmountain/sharp.html Once he was gone, the group chose Col. Campbell to act as commandant, and the combined force of 1,490 men continued the marched until they reached Cowpens20)Cowpens was the site of another decisive American victory just a few months later, in January of 1781. https://revolutionarywar.us/year-1780/battle-kings-mountain/ on the 6th of October. That afternoon, their scouts reported that Major Ferguson was encamped near the Cherokee Ford of the Broad River, some thirty miles distant.21)From Formal Report of The Battle of King’s Mountain Oct 1780 published in Virginia Gazette, 18 Nov 1780, also in Draper, p. 522-24. Accessed https://www.tngenweb.org/revwar/kingsmountain/formal.html

While the American militiamen gathered, Ferguson was encamped at Gilbert Town and received word of their impending move against him. Being in the backcountry and far from any reinforcements, he decided to march north to rejoin Cornwallis’ main force. As he fled ahead of the Overmountain Men, he continued attempts to raise Loyalist allies from the locals by posting a broadside. This broadside, like his earlier message to the Overmountain Men, did not have the expected result:

Denard’s Ford, Broad River,

Tryon County, October 1, 1780

Gentlemen:—Unless you wish to be eat up by an inundation of barbarians, who have begun by murdering an unarmed son before the aged father, and afterwards lopped off his arms, and who by their shocking cruelties and irregularities, give the best proof of their cowardice and want of discipline; I say, if you wish to be pinioned, robbed, and murdered, and see your wives and daughters, in four days, abused by the dregs of mankind—in short, if you wish or deserve to live, and bear the name of men, grasp your arms in a moment and run to camp.

The Back Water men have crossed the mountains; McDowell, Hampton, Shelby and Cleveland are at their head, so that you know what you have to depend upon. If you choose to be degraded forever and ever by a set of mongrels, say so at once, and let your women turn their backs upon you, and look out for real men to protect them.

PAT. FERGUSON, Major 71st Regiment.22)Published in the Virginia Gazette, November 11, 1780; found in Draper, 204, accessed https://www.tngenweb.org/revwar/kingsmountain/ferguson.html

Needless to say, Ferguson received no volunteers or support from the Carolina backcountry. During the pursuit, Campbell and the other leaders of the “Back Water men” saw how much the weaker horses and footmen slowed down their pace. They chose 900 of their best and fastest horsemen to ride all night to catch Ferguson. The slower troops were left to follow as they could, but wouldn’t rejoin their fellows until after the battle was fought. Militiaman Benjamin Sharp wrote in his diary of the march:

Thus disencumbered, we gained fast upon the enemy. I think on the 7th [6th] day of October, in the afternoon, we halted at a place called the Cowpens, in South Carolina, fed our horses, and ate a hasty meal of such provisions as we had procured, and, by dark mounted our horses, and after marching all night, crossed Broad river by the dawn of day; and although it rained considerably in the morning, we never halted to refresh ourselves or horses. About twelve o’clock it cleared off with a fine cool breeze.23)https://www.tngenweb.org/revwar/kingsmountain/sharp.html

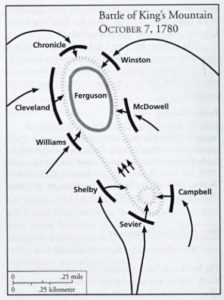

The nine hundred there were joined by Col. John Williams of South Carolina who had around two hundred men, swelling their ranks to about 1,100 men. It is interesting to note that, although both sides claimed to be far outnumbered by their opponents, the forces were nearly equal in number. At this time, they learned Major Ferguson’s troops were set in defensive positions on top of King’s Mountain, with men posted on the road and prepared to receive an attack. Campbell’s men overtook the advanced post and the Patriots maintained the element of surprise.

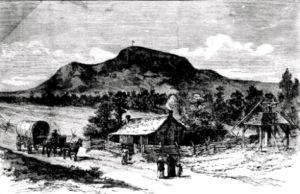

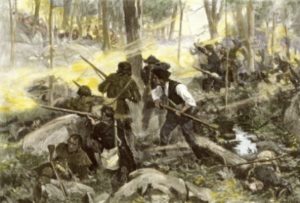

The top of King’s mountain is relatively low, reaching only about 150 feet higher than the land around it, and it’s shaped roughly like a shoe print with sides covered by trees and rocky outcroppings. Ferguson arranged his men into four defensive units around the broad northern end of the ridge, placing his wagons and headquarters in the narrower northeast corner. He elected not to raise defensive embankments, counting, rather, on the advantage of higher ground and the vicious bayonet charge. The terrain, however, was more to the mountain men’s advantage, and they didn’t need formal military training to know how to fight this battle. They arranged their many units to surround the enemy and slowly, quietly, worked their way up the slopes and into position. At three o’clock in the afternoon, they were spotted and the fight was on.

The mountain men wore no uniforms and were armed with their own hunting rifles, rather than the muskets favored by both the Continental Army and Ferguson’s men. The two weapons couldn’t be more different in their effect and use. The musket has a smooth bore that is quick and easy to reload, but only has an accurate range of about 100 yards. The hunting rifles of the frontiersmen were longer, slower to reload, and unwieldy for a battlefield, but perfect for hunting with a range of accuracy up to 300 yards. We have an eyewitness account from the Loyalist viewpoint in Capt. Alexander Chesney’s diary:

King’s Mountain from its height would have enabled us to oppose a superior force with advantage had it not been covered with wood which sheltered the Americans and enabled them to fight in their favorite manner. In fact, after driving in our pickets, they were able to advance in three divisions under separate leaders to the crest of the hill in perfect safety until they took post and opened an irregular but destructive fire from behind trees and other cover.24)The journal of Alexander Chesney: a South Carolina loyalist in the revolution and after. Ed. E. Alfred Jones of London England. The Ohio State University, 1921. P. 17. https://archive.org/details/journalofalexand00ches

In fact, the Americans were repulsed three times. Each time, they gave way in the face of a bayonet charge, took cover in the trees, and returned the move up the hill, all the while keeping up that devastating rifle fire. Chesney continues:

In this manner the engagement was maintained an hour, the mountaineers flying when in danger from a bayonet charge, and returned as soon as the British faced about to repel another of their party.25)ibid, 18

As the battle progressed, American forces gained the plateau and fully surrounded Ferguson and his men. Ferguson then led a fierce charge in an attempt to break through the lines and was killed.26)ibid Seeing the battle lost, Ferguson’s second in command, Capt. DePeyster, raised the flag of surrender.

Despite the claim of the Formal Report to the Continental Congress that “fire immediately ceased,” the killing continued for some time before the firing from the scattered victors ceased. Some of the militia wanted to take revenge for the massacre of Colonel Buford and his command earlier that summer at Waxhaws. The reason being, British Commander Tarleton refused quarter to the surrendering Americans at the battle’s end, and the entire unit was either killed or wounded.

The Battle of King’s Mountain was a complete victory for the Overmountain Men and the American Revolution. Ferguson’s entire command was either killed, wounded, or taken prisoner. Estimated casualties for Ferguson’s unit was 290 killed, 163 wounded, and 668 captured; while the Overmountain Men estimated 28 killed and 62 wounded.27)The casualties of the Overmountain Men are found in the Formal Report made to the Continental Congress referenced earlier. I found the numbers for the Loyalist casualties here.

The ramifications of this resounding victory (or defeat, depending on which side you were on) were great indeed. The report to the Continental Congress was delivered by one man who made a month-long, 600-mile journey. This news was just what the Congress needed. The loss of Ferguson’s entire unit reversed Cornwallis’ advance into North Carolina. Instead, he turned back south and the tide turned against him. A year later, on October 19, 1781, Cornwallis surrendered his entire army at Yorktown, Virginia. This was the beginning of the end to British rule in America.

Just like all such things, the motives and reasons behind the attack of the Overmountain Men are complex and, often, contradictory. The actions taken before, during, and after are never as clear and concise as we might like to think. But, one clear lesson can be taken from this battle: It’s dangerous to underestimate the people of Appalachia.

**Featured Image: “Death of Ferguson” / Artist: Alonzo Chappel, 1863 / Wikimedia Commons via Brown University from the Anne S.K. Brown Collection, Public Domain

References

| ↑1 | I won’t delve too deeply into the Treaty, but, essentially, it was a peace treaty between Great Britain, France and Spain ending the Seven Years’ War (aka the French and Indian War). The accord set boundaries for the settlements in America so colonies could coexist in relative peace. I found the language restricting expansion westward, across the mountains, rather paternalistic and condescending. Whether the real intention of these restrictions was to protect the Native Americans or to maintain direct control and power over such expansion, and whether any real will existed to enforce such restrictions, is a matter of debate. Accessed: http://www.tngenweb.org/tnland/intruders/17631007.html |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | His memorial lists him as a Colonel but he was a Major according to all the contemporary documents. |

| ↑3 | https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/10227/patrick-ferguson and https://www.britannica.com/biography/Patrick-Ferguson] |

| ↑4 | https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/10227/patrick-ferguson |

| ↑5 | Rifles and Riflemen at the Battle of Kings Mountain by National Park Service Public History Series number 12, 1941, p. 9. https://archive.org/details/riflesriflemenat12nati/page/8/mode/2up |

| ↑6 | Ibid. p. 10 |

| ↑7 | Ibid, p. 15 |

| ↑8 | https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/9507923/william-campbell |

| ↑9 | https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/25237945/andrew-hampton |

| ↑10 | https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/cleveland-benjamin |

| ↑11 | https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/11823/isaac-shelby |

| ↑12 | https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/john-sevier/ |

| ↑13 | https://www.carolana.com/NC/Revolution/patriot_leaders_nc_charles_mcdowell.html |

| ↑14 | https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/winston-joseph |

| ↑15 | https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/camden |

| ↑16 | https://www.battlefields.org/learn/revolutionary-war/battles/kings-mountain |

| ↑17 | King’s Mountain and its heroes: history of the Battle of King’s Mountain, October 7th, 1780, and the events which led to it. by Lyman C. Draper, published by Peter G. Thompson, Cincinnati, 1881, p.162. https://archive.org/details/cu31924032752846/page/n7/mode/2up |

| ↑18 | Quoted from Gov. (Col.) Shelby’s pamphlet published in 1823, reprinted in Draper, p. 562 |

| ↑19 | From the Diary of militiaman Benjamin Sharp, published in the American Pioneer in Feb 1843; accessed https://www.tngenweb.org/revwar/kingsmountain/sharp.html |

| ↑20 | Cowpens was the site of another decisive American victory just a few months later, in January of 1781. https://revolutionarywar.us/year-1780/battle-kings-mountain/ |

| ↑21 | From Formal Report of The Battle of King’s Mountain Oct 1780 published in Virginia Gazette, 18 Nov 1780, also in Draper, p. 522-24. Accessed https://www.tngenweb.org/revwar/kingsmountain/formal.html |

| ↑22 | Published in the Virginia Gazette, November 11, 1780; found in Draper, 204, accessed https://www.tngenweb.org/revwar/kingsmountain/ferguson.html |

| ↑23 | https://www.tngenweb.org/revwar/kingsmountain/sharp.html |

| ↑24 | The journal of Alexander Chesney: a South Carolina loyalist in the revolution and after. Ed. E. Alfred Jones of London England. The Ohio State University, 1921. P. 17. https://archive.org/details/journalofalexand00ches |

| ↑25 | ibid, 18 |

| ↑26 | ibid |

| ↑27 | The casualties of the Overmountain Men are found in the Formal Report made to the Continental Congress referenced earlier. I found the numbers for the Loyalist casualties here. |

Hi Tom!

Grant Mincy here. Just, got the chance to read this. A lot of very good information here. The hunting rifle bit I never knew before.

Hi Grant, glad you enjoyed it! It was a lot of fun to research and a challenge to write. There is a lot of nuance, and so much that could be included, before, during, and after the battle. As well as some very interesting characters and side stories. The opposing recollections and reports certainly make for interesting reading.

The rifle making the difference was particularly ironic given Ferguson preferred the rifle and was considered one of, if not the best marksman in the British Army. Some historians say if he had been able to outfit his entire unit with Ferguson Rifles there would likely have been a much different outcome, which may be true.

I don’t think that argument is as easily made as some think though. The Overmountain Men’s skill with a rifle wasn’t something they’d just trained for, it was something they’d spent their lives depending on every day, to support themselves and their families. They had also learned the tactics they used at King’s Mountain in the constant skirmishes with Native American tribes. Which is another, uglier story, but one for another article.

I really enjoyed reading this, Tom. I think battles must be hard to narrate, but you did a great job identifying people and movements. Great graphics. As usual, lots of good “look-ups” included!

Thanks, it was a pretty complex battle, even if it was only an hour long, and there were a lot of characters involved. Glad you liked it!