Our hike continues on in humid air with welcome breezes when, all of a sudden, I sense someone running behind me before hearing a terrified scream.

“Ah!” Katie yelps. “Oh my God, Casey! Help!”

I’m in the lead of our pack, but, startled, I turn around to my wife. Katie’s face is pale with fear as she clutches Casey’s hand fiercely. She pulls our friend along, and runs my way up the trail. I’m not too worried, though, because the chuckles from Casey and Ben let me know there is no immediate danger.

“It’s just a black rat snake,” Ben informs with a smile as he studies the reptile sitting off trail.

“Oh cool, I must have walked right by it.” I’m curious and pass by my wife to join Ben down trail.

“Seriously, Grant?” Katie gulps as she questions. “Just going to walk right by? Nine years today, punk-ass,” she scolds me endearingly. “Nine years!”

“You’re out of harms way now!” I return.

“Yeah, thanks to Casey, not you!”

Sure enough, curled up on a rock, is a rather handsome, not-too-large but certainly not small, rat snake. Shimmering and black in appearance, the snake senses our investigation, slowly unfolds itself, and begins a slow uphill migration in the opposite direction. We may have disturbed the ectotherm from some rest under the sun.

“We come in peace,” I assure the reptile.

“Grant, you need to walk next to me,” Katie asserted. As soon as she calls my name, I turn to her and smile.

“I’ll protect you,” I reply, “but it is a rat snake, nonvenomous.”

I understand my wife’s concern and, had I noticed the creature first, I would have likely needed to calm myself down as well. Still, this is a good opportunity to push her buttons a little bit. Unfortunately, a lot of bad folklore and horror stories are out there about snakes of all types. The tales are pervasive in the culture. Snakes, though, especially here in the Southern Appalachians, are an incredibly important ecological species. Snakes prey on rodents and keep a number of small, wild mammal populations in check. Aside from the rat snake, the Southern Appalachians are also home to copperheads and rattlesnakes. Though the latter two are venomous, they are not out looking for a human to fight and will only strike in self-defense – don’t mess with snakes, and they won’t mess with you.

As an important part of biodiversity, snakes are in need of conservation – as are their reptile siblings and amphibian cousins. At current rates of warming, global climate change will be too rapid for these animals to adapt and sustain their populations. Rat snakes, however, more than the copperheads and rattlers, and all their amphibian cousins, may fair rather well. Warmer temperatures here in the temperate zone will prolong their active hours and not just during the day as warmer evenings give way to warmer nights.

Though the rat snake may fair well, we will see a cascading effect on the rest of the local food-web. Increased nocturnal predation will result in the death of more birds who incubate their young at night. With poor visibility, the birds and their eggs will be eaten, thus reducing population numbers. Further, snakes are hunted by various hawk species throughout the region. If snakes become more active at night, which all available observation almost ensures they will, hawks will start missing meals. These majestic birds, as well, are at risk of sharp population declines.

The ugly truth about climate change is that this very real phenomenon has cascading effects across ecosystem stability. The rat snake, a friend of the ecosystem today, may lead to precipitous biodiversity declines in the future.

“I think I am getting hungry.” Ben hikes strongly and steadily as Ramsey Creek quietens his words. We are on a steep ravine decorated with impressive old growth trees, several hemlocks, and a shady complex thicket of mountain laurel. Soft needles from hemlock and other pine decorate the trail.

“Me too.” Both Katie and Casey reply in unison.

“Well,” I propose, “hopefully at the top of this hill we’ll find a place to rest a spell and get some lunch.”

I must admit, at this point in the hike, roughly halfway through, I am getting tired. My old hiking boots are worn. I just noticed the soles are pulling off from the boots, and, after a few creek crossings, they are wet and worse for wear. I still feel good mentally but my feet are feeling the burden. Plus, none of us find this trail as “easy” as the descriptions we read. As we make our way up a long ascent, overgrowth, often thick, covers the trail.

“I should have brought a machete!” Ben quips.

Thorns cut our hands and legs, poison ivy catches our skin, and our packs get caught on brush and tug us backward as we move uphill. We knew the length of the trail would be tiring, but we’ve also found this trail to be just about as knotted and rocky as any other trail in this national park.

“Great pick, Grant!” Katie mocks sarcastically with a laugh as we move towards our lunch spot.

“Yeah, I reckon I should have done more research,” is the only response I can mutter.

Under a break in the canopy, we find a nice place to rest for a spell. Once we sit, the sounds of packs being unzipped disturb a simple avian melody in the surrounding trees. I don’t have a clue what birds we are listening to, but they give us a nice opera as we chow down on our sandwiches and pass snacks around.

“Oh no. Shit!” Katie exclaims with a sense of wild panic.

“What is it?” Casey asks concerned.

“I’ve just about drank all of my water. I had no idea I was drinking this much. We have like eight miles left.”

With the new information we all decide to check our water situation and find we are all in the same boat. Now here’s the thing – each and everyone us out here today has climbed all over these damn mountains and we follow the same basic creed when it comes to food and water: overpack. We are all a little in shock to discover we’ve not packed enough, and further, that there isn’t an iodine tablet or a water filter among us. We’ve just realized, deep into the forest, that we have a very long way to go, on a humid first day of summer, without any replenishing source of drinking water. We’ve plenty of salty snacks, but water is rather imperative. I, for one, won’t take another sip so Katie can have what little is left.

After lunch, within an hour and a half of climbing and descending mountain trenches, braving a few more snakes among fallen logs, pushing our way through a trail that is overgrown, all of our water is gone – and we’ve much longer to go than we think.

Water is essential to all life on Earth. In a fundamental analysis, the cells that make organisms use membranes to separate living beings from their environment. Water is necessary for life because the solvent is liquid at our planet’s surface temperatures. This liquid nature, and ability to dissolve minerals, nutrients, and metabolic waste, provides an efficient way to move energy and waste from a cell to a cell’s environment. In other words, water brings the good stuff in, and gets the bad stuff out of a living organism. Having liquid water is what makes Earth a living world. This, too, is a cosmic tale of the sun.

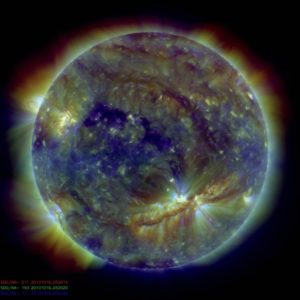

Our central star emits a ton of radiation toward space. Every once in a while, large explosions erupt across the surface of the sun that send wave after wave of life-destroying cosmic energy, burning at several million degrees Fahrenheit, hurdling across the solar system. These explosions are known as solar flares and they occur near sunspots, usually between the dividing lines of opposed magnetic fields.

Earth is not immune from this violence. Solar flares emit x-rays and magnetic storms that shower and bomb our rock as geomagnetic storms. When sunspots are active, harmful radiation from solar flares bombard our living planet, wave after wave. When sunspots are at a maximum, especially this time of year, the aurora in the northern hemisphere will shine much more brightly. We think of the sun as the star of life, but these emissions are just one way the sun can end all of conscious existence. In space, this same radiation has removed all liquid water from the surface of Mars – ending the possibility of a Martian multi-cellular evolution that the Earth has experienced over the last two and a half billion years. This begs the question, what makes Earth so special?

The answer is Earth herself. Our planet is layered, much like a medium-boiled egg. The soft shell of the egg represents our planet’s crust. The crust is what we walk on, and it is made of lighter elements. Beneath the crust is the mantle. At more than eighty percent of Earth’s volume, this layer is predominately a solid mass of silicates laden with magnesium and iron – think of the white albumen of the egg. Over geologic time, the mantle acts as a viscous fluid. That activity brings us to the Earth’s liquid outer, solid inner core, or, the medium-boiled yolk. The core is incredibly hot and under an immense amount of atmospheric and planetary pressure. This layer is dense and full of heavy metals like iron, nickel, and lead. The core holds the key to our planet’s survival.

As the sun hurls deadly radiation our way, our core, via the motion of convection, creates currents within the molten mixture of heavy metals at our planet’s heart. These currents are caused by all the heat that escapes the core. This process fuels plate tectonics and builds our very own magnetic field. This magnetic field, powered by metals spinning constantly in a melting furnace, saves us. Without this layer of protection, solar winds and flares would blow away our atmosphere and evaporate all the water on our blue marbled planet. The magnetic field travels four-hundred-thousand miles into space, surrounding our living home. The magnetism acts as massive force field that deflects all the deadly radiation that destroyed Mars long ago in the cosmic past. The Northern Lights, all our planet’s mesmerizing aurora, is the direct observation of the sun’s violent radiation smashing into our own magnetic field, keeping life in the known universe alive. Homo sapiens are but one animal on a living planet searching for meaning under the stars.

Our star is primarily made of hydrogen. In an unimaginable furnace, at incredible gravitational pressure, the hydrogen atoms at the sun’s core fuse together to produce helium. This fusion tells us the sun is expanding. In the last 4.5 billion years, roughly half of the star’s hydrogen has fused into helium. Looking to the future, as hydrogen becomes exhausted, the sun’s temperature will cool and the burning star will expand across our solar system, across our planet, and out to Mars. Billions of years from now, the sun will be what physicists call a “red giant.” The star will glow ten-thousand times brighter than present luminosity. All life on Earth will be long over, emphasizing that future Earthlings, whatever strange beings have evolved, whatever their powers, no matter their understanding of the great beyond, will have to use available knowledge and move outward to explore the depths of the cosmos so that Earth’s living legacy can persist. After this red-giant phase, the sun will reduce to roughly the size of our now living planet and slowly cool for billions of years. In the fabric of space-time, all possibility for life will have disappeared from the only solar system life has ever known.

Our legs are weary; our feet sting and ache with pain; our saliva has dried to a gummy paste in our mouths and across our lips. With every hill, with every round of the trail, every welcome breeze, we have the hope of finishing. We keep pressing forward. We are deep into this long hike and have no idea how far we still have to go. This overgrown, knotted, rocky, trail full of thorns seems never ending. Such is life in the unforgiving cosmos.

In all our misery, I cannot help but smile and offer chipper words of encouragement to Katie: “We are going to look back on this fondly!” The thing about wilderness is when we’re ragged and tired, beat up and exhausted, life is more interesting.

“I could cry my feet hurt so bad,” Katie whimpers. She stops as we leave a narrow piece of trail, just past a stone wall, to find yet another switch-back. “I’ve got to sit down for a while.”

“We are close to eighteen miles here, what the crap is going on?” I complain and sit down next to my wife. My aching feet scream in relief as I take my body weight off them.

“I don’t know, but I’m not having fun anymore, baby. I really need some water . . . and wine.”

“Yeah, I’m ready for this to be over, too. A cold road beer is going to taste great.”

I’ve enjoyed our time out here – the struggle, the welcome breeze, the pain, all the plants, especially the titans of old growth, rhododendron, and mountain laurel thickets, the quivering ferns, the cool waters that glide over smooth rock. At this point, however, the pain, especially in my feet, is growing tiresome, and we’ve traveled miles and hours without water. Casey and Ben are somewhere behind us. They paused for a break, but Katie and I didn’t because were too worried that if we’d stopped it’d take a miracle to get us moving again. Now, far past what we thought should have been the end of the trail, I am very much hoping for a miracle. But all I see is another deep, natural trench to climb out of.

This deep, natural trench to climb is a perfect allegory for the planetary experience – as protective as planet Earth is at harboring life; all living creatures here, Homo sapien included, are faced with the eventual demise of life in this realm. Experiences like this remind the human animal about the importance of wild spaces. These spaces of refuge and recreation are also spaces of danger and exhaustion, even death. Our species, all the lives before us, all possibilities for future generations, will have to rise to planetary challenges – climate change, pandemics, disasters, and the eventual off world escape. Away from the comforts and confines of civilization, human beings find environmental wisdom. We need the preservation of wilderness to know our own wildness, our own vulnerability. Only this realization will carry organized human existence through the challenges unfolding all around civilization in this 21st century.

Katie and I sit in silence for ten minutes or so, letting our bodies ache and our hearts calm down. Fragrant sassafras, sweet and sugary, fills the air; young hemlocks cast a shadow of cool shade; maples and oaks tower over the canopy as the thick foliage lays a dark shadow across the soil, stone, and leaf litter of autumns past. I look all around this environment, miserable, but contemplative. As my gaze falls on an old growth hickory, shedding bark but still standing proud, I know we’ve come to the time to start moving again.

“Okay, Katie,” I half mumble, half groan as I struggle back to my feet, “we need to get moving again. Can’t stay down too long.”

“Fine.” Katie flips me the bird as she climbs to her feet. “But I think you’re a punk-ass.”

“What are you talking about? This has been an easy, rolling, splendid hike. Just breathe deep all this sweet and lucid air!” I exclaim, inhaling broad and deep, with my eyes closed and arms extended. “Let your senses fill your heart with warmth, and joy, and love!”

Katie looks at me with a raised eyebrow and slightly parted lips before saying,

“You’re weird, Grant. Let’s walk.”

We chuckle and begin another gradual climb, several hundred yards, until we descend towards a long hollow where our trail finally straightens. Hiking through the flat, the faint laughter of little ones echoes through the lonely wood. Katie and I gaze at one another and smile in that knowing way parents do when hearing children at play. She and I cheer, whoop, and holler right along with them. We feel incredible relief, knowing the trail will finally end. When we reach the parking area, we sigh with relief. Immediately, we limp, feeling broken, to our car, take off our musty, sweat ridden boots and socks, and slip into our own pairs of comfy Crocs – hers decorated in a bright rainbow pattern, mine camo.

Turns out, Casey and Ben are not very far behind us. After snapping pictures and telling stories, we hop in the car to end the day’s adventure. I slump behind the wheel, exhausted, start the engine, and we’re off. I glance at Katie whose eyes are closed meditatively, and my thoughts wander to our wedding day some nine years ago. One of my favorite pictures of that day is of my mom and grandma. The three of us are sitting at a table in the old Sunspot down on Cumberland Avenue and the emerald green wall behind us perfectly highlights my grandma’s mood. She wears a light, white jacket, and a giant grin spreads across her glowing face. I sit next to her in my suspenders and orange bowtie, beaming just the same. On the other side of me my mom sits in her blue dress, also with the same smile radiating across her face. I love that picture, not because our inherited characteristics are on full display, but for the fact those two women, and the memory of Great Grandma Shorty, hold a huge influence over my life.

Our wedding was a special day. Along with my aunts and grandma, my grandpa was there, having traveled with them from Michigan to be with us. I was also very happy to spend the day with my dad and sister, who also made the trek down from Michigan. My parents had recently separated; I didn’t realize this then, perhaps I should have, but this would be the last time the three of us would ever be together in the same place. Katie’s family – two of her brothers (who will grow to be good friends of mine), her mom and stepfather, along with her dad and stepmother – celebrated the day with us as well. The family Katie and I chose, the friends we had made along the years who continue to shape who we are, were there too, of course. And isn’t this kind of setting what human life is all about? The same folks who knew, loved, and raised us as children, meet the shared world that two people built together and celebrate our decision to move into the future, support us as we tackle life’s burdens and struggles, and share in all our joy, all the while loving each other in the still, silent moments. Weddings are a celebration of life, past, present, and possible futures.

“Hey, a small mountain grocery!” I hurriedly flip on the blinker. “I want their biggest water, and their tallest ice-cold beer.”

Once parked, we all pop open our doors and exit. My body aches and my legs wobble as a laser of pain hurtles from my feet to my hips. My companions must all feel the same because, as we crawl out of the trusty wagon, collective groans all around fill the air.

“Ow!” We all say in almost perfect unison as we chuckle together and limp inside the store.

The store is nice and clean. A semi-sweet fragrance of fried pies and bread lingers in the air. We pop open the coolers and grab the biggest waters available. With water in hand, we look for beer. Now, my taste buds have been screaming for some kind of American lager for hours, miles upon miles at this point, and, as I scan the remaining coolers, I realize there ain’t a drop of booze in sight.

“Damn. No beer,” Ben grunts. He’s obviously feeling the same way I am. We both frown at one another.

“I guess we’ll just have to buy the rest of the beverages,” I say gloomily.

Losing the beer ends up not being so bad. Casey has already picked up an RC-Cola to wash down what I eyeball to be a Moon Pie in her hand. My wife as well holds an RC-Cola, plus one of our all-time favorites – the Dr. Enuff.

“Oh, hell yeah you guys. Great picks!” I quip happily as I pull open the cooler. “RC-Cola sounds great. I’ll have myself a Dr. Enuff, too, and while I’m at it, I’ll get myself a Dr. Enuff Cherry.”

The women laugh at me as I cradle everything.

“What?” I question, “they have essential vitamins and nutrients!”

Back in the car, we chug our waters but decide to crack open our RC-Colas together. I hand my fizzy delight to Katie, who uses a can-opener to pop the top off the glass bottle. She hands the sweating drink back to me. With cold bottle in hand, I take a sip and my mouth explodes with effervescence, a rich almost caramel flavor, overtaken by an incredible, fragrantly sweet taste of natural cane sugar.

“I think this is the best damn soda I’ve ever had in my entire life.” Doesn’t matter who uttered this phrase, perhaps we all did. We were all sure as hell thinking the same thing. Such a simple pleasure after such a hard day is incredible.

After dropping Ben and Casey off at their car, Katie quickly falls asleep. Alone with my thoughts on our long drive home, my mind wanders. Days like today teach us that a landscape is splendid and dangerous. Further, that landscapes are best understood and given human significance by human labor. Landscapes are felt and loved by those of us who have not yet lost the capacity for wonder. Mountain country does not always inspire love – yes, wilderness is dangerous, enter at own risk, carry water, curse frequently. But wilderness is a treasure to be enjoyed in body and spirit. Wildness is a human treasure too valuable, too rare, too precious to be held from our children and all future generations. The wild ensures that all civilization has a chance to be free, a chance at a discovery of self – to be part of a mystery of the whole. In my view, no better place exists to re-imagine human civilization than our wild, anarchic, pure places. The imperative time is now to challenge our history so we may cultivate a sustainable future together – to embrace a wild liberty, a natural freedom, an unshakable humanity.

These lands belong to everyone and to no one.

Grant, thanks for taking us along on your family adventure. As someone who has bitten off more than he can chew on a number of outings, I feel your pain. An excursion can look so beautiful in the abstract—say a black dotted line meandering across a green expanse of flattened contour lines on a two- dimensional map—then on the big day, three-dimensional reality hits.

Thank you for another wonderful blend of family, adventure, misadventure, science, philosophy, and poetic language.

And Congratulations on your appointment as Science and Environmental Scholar!