Grace put the top down on the old Miata and we burned the open road, our hair spinning wild as Medusa in the crisp late spring. We should travel to Monrovia, California to see Upton Sinclair’s house, she had said, and take one of those cross-country road trips on our way. Take your mind off things. I was out of sorts since my divorce was finalized two weeks before. Alex didn’t take my leaving too well and, quite frankly, I was afraid of him. He’d raged at me on the courthouse steps. “I’ll have you done in,” he had said. He was a low budget defense attorney but he had clout with all kinds of people. After his threat, I’d made a beeline to Grace’s house, shaky and petrified. I remember she pressed a glass of chardonnay in my hand and suggested we take this little venture. I’d read a good portion of Sinclair’s writings and always wanted to see where the man made his bones, so to speak. So, here we were in the convertible as the sun beamed down and purified my spirit. We decided to rediscover our founding mothers and fathers along the way, and visit sites where pride for land and country loomed on every stone, crevice, or piece of paper. Coming all the way from Pressé, North Carolina, we had every intention to stay on course but we found ourselves a detour in Firmwright, Mississippi. Grace pulled the Miata on a graveled shoulder and the tires sluggishly crunched the ground.

“There!” Grace exclaimed, pointing a pale, sangria nail to a considerable, sprawling plantation. She pulled back her tousled fiery hair in a pony tail. “Let’s go there. The sign says the tour begins in thirty minutes. We can walk around, enjoy the history, and get a hotel here for the night.”

“Sure,” I said, smiling. I craned my neck and surveyed the land. She parked the car and we walked to the end of a good-sized line.

A mutton-chopped man with a small megaphone sported a costume right out of the mid-1800s. He bellowed in a thick, southern drawl:

“Ladies and gentlemen, tooahs for the unfagettable O’Sullivan Plantation experience begin in fifteen minutes. Please step through the corridoah, take a numbah and a key. Leave all possessions, includin’ puhses, wallets, phones, etcetera, inside the lockah provided. Your unique encountah begins shortly. Kindly pay eighteen dollahs per person to tooah guide, Mastah William, near the entrance. Ah thank you.”

I gave Grace my money and asked her to pay for me, then excused myself to the restroom. She and I set ourselves apart from the guide. We meandered mildly through the estate grounds, taking in the milestones. I moseyed toward a chain-link fence by the sidewalk and curled my fingers through the mesh. This was a quaint little town, really. I guessed it was spring break because across the street, Norman Rockwell’s freckle-faced boys parked their bikes, flicked their kickstands, and walked with wadded dollars toward a Mom & Pop restaurant window. A few minutes later, each one breezed back to his bike with an ice cream cone and grins as big as crescent moons. One of the boys looked at me, smiled, and nodded, which jolted me into the realization I was away from Grace.

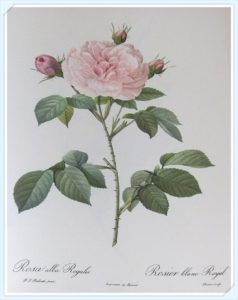

I turned to find her but was stopped by an aroma – a dewy, elegant scent – that lingered in the air. The smell enticed me. I drifted along to find the source. The fragrance was mild at first, but, as I moved closer, it intensified and drew me to it. I stopped when I found myself facing mounds and mounds of elegant, pink, round roses. The scent hugged me in comfort and sweetness. I closed my eyes and the ambiance took me back to a vintage day – a time when women sat outside on their verandas in summer, fanned themselves, and sipped mint juleps. I envisioned their mustachioed men congregated nearby, underneath a shady tree, standing stiff and jocularly debating. I opened my eyes and a sharp realization stabbed the ether. My face reddened.

“White women, white men,” I whispered to myself. “Remember where you are.”

But the impulse to extract myself and flee to a world of unreality was too great. I closed my eyes again. My little world was interrupted by a booming voice in my ear,

“Ah! The Maiden’s Blush!”

I gasped, squinched my eyes, and flinched out of habit.

“Oh, pahdon me, ma’am,” said a sinewy old man in dark period garb. His gray and frazzled hair jutted beneath a bowler hat. I guessed he was William, the tour guide, whom I had avoided since the tour began. He continued in a genteel southern drawl,

“I was merely,” he began, tipping his hat, bowing slightly, and waving a rawboned hand across the pink flowers, “commentin’ on the Great Maiden’s Blush here. Planted by Salina O’Sullivan well before the Civil War.”

He moved toward the flowers and I watched the roses recoil with my own eyes. He plucked a petal, held it to his nose, and smiled. His eyes spoke of remembering.

“She was married to a fine man,” he said, flicking the petal to the ground, “a good man. And she was his pleasure. But she was suhtainly her own woman. So sad. So sad, what happened to her.” He shook his head. His countenance took on a darker quality and his eyes burned into the roses.

I was all too familiar with his savage stare. The last time I saw such fire was on the courthouse steps. And before that, I was greeted daily with those same burning eyes until I left in 2011.

“Some say the roses, they talked to her. Persuaded her with their stigmas,” he said, embittered.

I put my head down and stepped backward. His eyes never strayed from the bushes as he stepped back with me in unison.

“They flourished and peaked aftah she cut them, you know. Some say these roses watched her with their fine pistil orbits, swayed to her hums and music, snug in their centahpiece. She’d widen and arrange them, her breath heavin’, her arms flailin’ every-which-way, to present their puhfect, grand showpiece,” he said.

I cleared my throat and cautiously stretched my neck to find Grace. This man was, hands down, the strangest tour guide I’d ever known. My furtive gaze searched for clear exits and noted weapons. I had mace in my purse, but a lot of good that did me, since it was confined to a locker, per the museum’s direction. I noticed several large river rocks lining the base of the roses and told myself that would do nicely. He appeared not to notice or care about my uneasiness and resumed,

“When the dinnah bell rang, guests swore the roses’ faces tunned and watched the great hostess, Salina, from their noble arrangement on the long dinin’ table,” he said, moving forward. His skeletal fingers pinched off a browned leaf.

He smirked and stepped closer to me. I stiffened and tucked my arms tightly near my sides so as not to touch him. I dug my foot into the “shag-ass position.” He went on,

“She had her own little seeds, you know, a girl,” he said, “then she had a boy, then anotha, and anotha. Ten O’Sullivans, back to back. Nine of them boys. And all of them cried and bawled and hollered for Salina. The roses, too, demanded her devotion. She had no time for her fine husband, who kept his good commitment and performed his duties. They say she wrote in her diary about bein’ ‘endlessly home where grandness smothas.’”

His hands popped and cracked into balled fists. Time to bolt, I told myself. I edged slightly from him and spun halfway. But, without warning, he gripped my arm, latched and squeezed his elongated fingers, and pulled me to his side.

“One night,” he seethed, tilting his head skyward, and motioning his other hand up the house, “she went up to the roof.”

I was compelled to look, but my mind churned for an escape route.

“She stood up there a long time. Lookin’ down at those Maiden roses and smilin’. Her darlin’ husband stood right about,” he said, dragging me over a few paces, “. . . here.” He looked down then glared up again.

“Why, I can almost see her now. Standin’ alone on the edge, feminine, light, and pink as those damned Maidens. Crisp and bright in her nightgown like the moon and stars behind her. Then, out of nowhere, she boldly roared: Love thou the rose, yet leave it on its stem! She dove, spread-eagle, like some invuhted Phoenix, right there in the middle of the rose bushes . . . and she nevah came back.”

“Some say,” he said, dully, loosening his grip, “Some say she’s still there below the mounds, underneath the Maidens, scratchin’, diggin’, grabbin’, clutchin’, searchin’ for the meanin’ of it all.”

I heard voices behind me. Thank God, I told myself. I turned from him and staggered away but fell in the process. My hand fumbled upon a river rock. I jerked it up and held it, ready to swing in his direction – but he was gone. All of a sudden, I heard Grace’s broken sentence.

“. . . worried because I couldn’t find you! We saw you get up from the ground a little wobbly. Are you okay?” Grace asked, looking at the rock in my hand. I threw it down. “What’s the matter?”

“Th – that man. William? The tour guide,” I said, panting, “he was here telling me this god-awful story about some woman who lived here before. Oh, Grace, it was awful,” I said. “We’ve got to get outta here. I’ve gotta get outta here!”

A young, slender African American man walked up with a bottle of water and a wet towel. He wore a purple polo, stitched with the words Mississippi Historical Society on the front pocket.

“She okay?” he asked, handing Grace the water bottle and towel.

Grace had me sit down on a bench near the roses. She took the towel and wiped my face, opened the water bottle for me to drink, then fanned me with a museum brochure.

“I think she’ll be okay, William. She seems to be coming around,” said Grace.

“William?” I asked. “You’re William?”

“Yes, ma’am, ah surely am. Ah do b’lieve you fainted, ma’am. We – your friend and I – saw you scramble to get up from a sittin’ position. You looked ratha unsteady on your feet so ah rushed to getchoo a towel and a little watta.”

“Fainted?” I asked, perplexed. “But, I swear, Grace. I saw him. I spoke to him.”

“Him who?” asked William.

“A man. Here by the roses,” I said, pointing the water bottle in that direction.

“What’d he look like?” asked William.

“Well, he was pale, somewhat sallow. Gangly. Wore an old-timey black suit, a white shirt with a bolo tie. Had the awfullest bony fingers. Wild-looking hair underneath a derby hat.”

William put his head down and sighed.

“Ma’am, ah b’lieve you’ve encountered Mr. Colin O’Sullivan,” he said, “original ownah of this plantation. Salina was his wife of nineteen years. Self-educated woman, despite this here region. They say she charmed flowahs and the flowahs spoke to her.”

Grace and I exchanged a quick glance.

“He couldn’t have been a ghost. He was as real as you are!”

Grace handed me the towel and patted my shoulder. William went on,

“Ms. Salina vanished around 1850 or so. Jumped from that roof,” he said, pointing up, “three stories and, poof, she was gone. No blood. No body. No footprints. Just . . . gone. Like she soared right into the roses and disappeahed.”

“People – in particulah, women in distress – say they’ve experienced Mastah O’Sullivan here at this plantation. Much in the same way and always beside the Maiden’s Blush. Ladies, I must retunn to the group. However, I’m not opposed to stayin’ afta and talkin’.”

He turned and walked toward the house. Grace frowned and wrung her hands.

“Maybe we ought to just go. What do you say?” she asked.

Grace had been so kind to me and seen me through all this stuff with Alex. She’d planned this whole trip and I had no intention of disappointing her.

“Oh, Grace, no. I feel much better, I promise. I’m inclined to believe I did faint, actually. The last thing I remember, before that creepy man, was when I closed my eyes and imagined the antebellum days. I probably conked out and dreamed the whole conversation,” I reassured her.

I rubbed my arm on the spot where the man grabbed me. I refused to look and see if there were fingerprints. I didn’t want to know.

“Okay, but anytime you’re ready to go, we’ll go,” she said.

“Deal,” I said.

Though I felt drawn to the Maidens, I placed the wet towel on the bench and walked away. I realized I left my water bottle and went back. When I bent down to retrieve it, I felt the earth slightly pulsating, and saw it rise and fall like someone underneath gripped the bushes’ roots and pulled. I staggered backwards then fled to Grace, locked arms with her, and headed for the entrance. I looked back, and, even though I understood the span of distance, the roses somehow moved closer. We reached the entrance and rejoined the crowd.

Grace was occupied with some vintage artifact so I wandered into the study. I spotted a sign that said “Salina O’Sullivan Desk” and ducked underneath the rope barrier. I hesitated and heard no alarms. I ran my hand across it and felt the smooth walnut and rosewood. I peeked inside one of the drawers and found words etched into the base. I bent closer and read: He led me to believe he saw me differently.

My teeth clenched. I didn’t need to read anymore. I understood. A person made believe they loved you, then treated you any which way – differently – once they had you.

After that, I moped along the room. My eyes caught a small “Employees Only” door. Intrigued, I pushed it open and was greeted by a set of narrow, upward stairs. So, I climbed until I reached a small sitting room where sunbeams streamed through a good-sized window. Its cylinder glass must’ve been original because the outside view was wavy and distorted. I leaned forward and looked down. The hazy pink roses spread out toward the back. I smiled at them.

A swaying movement caught my attention. I dropped my smile and squinted until I made out a blurry figure by the roses. I strained a little harder and saw it was a woman. Her dress seemed old-fashioned though not quite antebellum. And she appeared to be waving at me. A realization burst inside me. I wasn’t supposed to be here. My heart raced as I jumped away from the window. I turned to cut and run and find Grace. But, when I took one last peek out the window, five women stood waving by the roses. I smoothed my hand along the window pane and found a hinge. I opened it and peered down. I saw no women. My eyes darted toward something like a shadow, murky and indistinct, near one of the columns. Maybe the women had waved at someone farther up. I twisted my body a little out the window and craned my neck to see. No one. But I did see a small platform by the attic window and wondered if the women waved at someone there. This venture became something of a mystery I wanted to solve.

I found more stairs behind another door and they were even narrower than the first. I was a small woman so I hugged myself tight and moved gingerly until I reached a stifled attic full of the usual memories and remnants. A touch of light leaked from behind a set of boxes. I heaved them to the corner and waved away the dust. A tall side window stood, almost like a balcony door. I opened it and faced the little platform. I sat on my knees away from the edge and looked down. People milled about the museum stables. Couples sauntered through the gardens. Families had lunch on the veranda. My heart sank. Before my marriage, I’d have been right there among them. Now, I felt so disconnected and walled in by my own insecurities. I watched Grace running from here to there, probably looking for me. I laughed and stretched my arm to wave and call her name. Yet, I was distracted by the rosebushes because they swayed and undulated. Then I saw them: The Women. They emerged from beneath the roses.

The Women, numbering five, were dressed in period garb. I couldn’t be sure but it looked to me like they wore dresses from each century dating from 1600 to 2000. No one else down there seemed to notice them. One of the Women stood in front of the rest. She was stunning and regal in her lemon chiffon dress. They never opened their mouths but spoke to me telepathically. I heard them clearly. They said,

Come, Sweet Daughter. Come and join our found sovereignty.

We who tend or pull roots at will. Come where we are glorious.

Where fulfillment births from the Mother seed. Come home to us.

Stretch out your arms and dive into the immortal soil underneath

humanity. Come. Tributes for us will last a thousand lifetimes!

I shook my head but something about their words and intonation was calm and soothing. I turned away from them and buried my face in my hands. The torrent from my pains heaved and flooded. For years now, I ached to be away – away from restraining orders that weren’t even good enough to wipe my ass; away from all forms of meanness and bitterness and hatred; away from a world where dearth of knowledge is king. A world of destruction and apathy, where children are abhorred when they hunger, where young people die trying to escape it. I was weary of treading water, seeing the distant island of hope, but making no headway. I grew tired of threats and hypervigilance. Tired of my spirit being broken day after day, after day.

“I don’t want to be at war with the world anymore,” I said aloud.

I wiped my blotchy face with dusty hands and looked down again. My mind was so addled, the ground seemed to bounce up and meet my eyes. The Women’s arms stretched open and reached for me. But, once more, I shook my head. The height was dizzying and I grew light-headed, swaying softly around and around.

I hadn’t remembered stepping onto the platform but there I was, teetering, woozy and weak-kneed. They were reaching for me. Come. How comforting their arms looked. How restful. And I was so tired. Come. I caught a glimpse of Grace down there. Her eyes widened with panic. Her mouth was agape with emptied screams. But I could not hear her. Come. All was silent to me apart from these Women. Come. I looked down and smiled at them – my Sisters, my Mothers – all fused and united in the earth. I felt muffled footsteps advance, brushing up the narrow stairs. Yes, I told myself, nodding. Yes. I spread out my arms, turned my face to heaven, and smiled. My stomach whirled with butterflies. My body throbbed with exaltation. This must’ve been what it felt like for her and for all of them. It was my time. For once in my life I made my own decision without interruption, fear, or self-doubt. I looked down and dangled one foot in the air. Suddenly, the color drained from my face and I struggled for breath. Right before I soared from the platform, I saw the old man. He moved like a shadow in the crowd. His gaunt eyes found mine and he tipped his bowler. He spread out six scrawny fingers then pointed at me. He flashed a knife-edged smile that bared too many teeth and laughed when my foot slipped.

This is wonderful!

Thank you, Trent. It’s quite different from my usual writing style.