We lived in safety in a holler down at the foothills of Appalachia. We was holed up in a big compound with highwalls and all manner of protection and arms. The place used to be a gated community. Our folk took to callin’ the place The Kingdom. We’d learn about survivin’ and read the scriptures, the old ones and sometimes even them new ones, the ones about the end a days. We never went out The Kingdom much; Daddy and his “brothers” would always go and raid, bringin’ back food and spoils of war.

One day though, Daddy got kilt, by some protestors, or counter protestors, anarchists, or vigilantes, maybe even cops; hit was getting kindly hard to tell what folks believed in or fought and died for these days.

Was around that time all my weird uncles, Daddy’s brothers-in-arms, started comin’ around more often to our bunker . . .

They helped out, my uncles, whenever they could, with staples, rations, and basic work around the compound and the farm.

Some of ‘em looked at Mama real strange, and Mama kindly told ‘em to stop.

Willem and his brother been comin’ around less.

They ain’t so much as helpin’ out these days. A dozen full-growed, sweaty men with minds set on nothin’ more than violence and eatin’ all our food don’t do much cleanin’ up after themselves.

Over time, we see less and less of them. First Willem and his twin brother, Woodrow, take off with Billy the Skid, Mark Abbott, Jerome, and Biggs. The ol’ one-armed guy, Corbin, and a bunch of the other ones Mama calls “scavengers,” stick around a little longer, branchin’ out from my family’s house but still roamin’ the main compound. One day, we see Corbin sneakin’ around our quarters, behind the inner gate, lookin’ in our windows. Mama catches him and cusses him and he runs off. When Corbin takes off, the rest of ‘em finally scuttle outta The Kingdom.

Mama says, “Good riddance! They’re like rats fleeing a dyin’ ship. Nothin’ but traders.” Or maybe she says “traitors.”

By the time my uncles stop coming around The Kingdom altogether, Mama’s sure they’s going over to Kansas City.

Mama leaves late one night with her gunmetal-grey AR-15, Daddy’s Dodge with the sheet-metal paneling, and the last dozen bottles of Kentucky booze she ain’t already guzzled in her griefs.

“Where you going?” I ask her.

“Don’t you worry, Tobias. I got to set things right. Them good fer nothin’ uncles of you’rn been selling secrets to our enemies, runnin’ they own patrols and givin’ away the locations of our compounds, sharin’ our supplies with heathens and freeloaders!”

She’s deep in her cups—drunk on the mason jars of shine and the bonded whiskey in them fancy bottles, and she’s overcome with paranoia and rage. Stepping into the war room, she spins the big vault door. Stopping for a while to look at all the weapons, she continues talking, not to me, but to ghosts.

“We built a community, a group of people who’re tired of takin’ shit from everybody, and we band together, to survive! The bigger your daddy built up this kingdom, the more room there was for the snakes to hide . . .” She passes over a bunch of our rifles, then stops on an olive-drab crate, a baker’s dozen of hand grenades.

“Mamma, please, the other chapters can help us. Willem said he would always be there for us!”

I place my hand on the bony, withered shoulder. The husk of my mother struggles over the explosives, tossing aside the duds and dummies like she don’t care if one happens to be live.

“Ain’t a one a them can be trusted or counted on when the Lord’s work requires true sacrifice. They’s serpents every last one, Toby. Willem and his good fer nothin’ brother been going up to Kansas City, and they sold your Daddy out for a couple hours with little girls, and even boys like you!” she exclaims through tears.

“Mamma, we’re safe in here though, right? We can lock up the gates and we can watch the walls ‘round The Kingdom like Daddy always says . . . like he always said. ‘Sides, we got all the food and supplies we need, so we can live long, right? We can survive?”

She looks at me, long and weary.

“You just stay the hell away from that band of Judases, ya’ hear? I got to rid the Earth of them, I got to make them pay. You stay in here. In these walls. Take care of yerself now, baby boy. Remember your Mama loves you.”

I never see her again. Only in my dreams.

Off the main roads, deep in the Appalachian wilderness. Light creeps through the scorched pines and desaturated dogwoods. A burnt out clearing where the TVA and then the forestry service and then the scavengers and then the blood cults have hacked away at the encroaching wildlands in favor of some more corrupt enterprise.

A circle of men, and their mean women, too. Some are just boys. Their clothing, ragtag, pieced together, a motley of fatigues and coveralls, tacky pairings with polo or Hawaiian shirts, flags, chains and flak jackets, weight plates, waistbands, boots, holsters, paraphernalia of combat, the iconography of patriotic pride and prejudice. The only requirement, the only uniformity of their uniform, the obligatory AR-15.

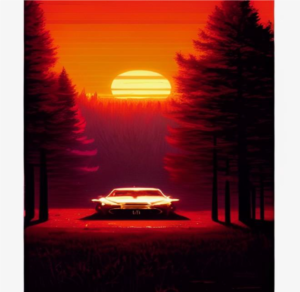

She loads her trusty weapon, as American as apple pie. The bottles of alcohol and their oily rags therein are just the propellant she needs to unleash hell on these dogs. Shifting the gears and revving up the Detroit import, she charges on, ramming these stand-ins for all evil, these icons of corruption. They light ablaze like effigies. She burns as well. Smiling. Dying for nothing. Dying for everything that is left and everything that ever was and the absolute absence of everything that was to be.

When I wake up, I have a eerie feelin’ in my gut. I think my uncles kilt her, and I hope, at least, she kilt summa them, like, a eye for a eye. Willem and the rest of my uncles, if they was still out there, they’s likely to be dead or dying, burned, or burning.

The whole country is.

The whole world is

Vincent Bernabeo holds an MA in Literature & Writing Studies from California State University, San Marcos. His interests range widely as he works across genres, media, and modalities. He asserts all media has valid literary merit. Vincent recently moved his wife and kids to East Tennessee in a move antithetical to his literary heroes, Cormac McCarthy and William Faulkner, who both began as Southern writers and moved to the Western United States. Vincent’s roots and family ties are deeply seated in the Appalachian region, and his hybrid experience growing up in Southern California and the American South informs his work.

**Featured image by Cottonbro Studio on Pexels