Revisiting Myles Horton’s The Long Haul

The remarkable thing about Myles Horton is that he chose to be a person instead of a personality. As a rising young labor organizer and civil rights activist, Horton was surrounded by personalities – a cadre of forward looking, socially attuned recruits, some who, in time, became household names: Pete Seeger, Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks, and Ralph Abernathy.

Horton’s upbringing undoubtedly contributed to his status as a social warrior. Born in Savannah, Tennessee, in 1905, Horton embraced his family’s rigid Presbyterianism until of age to question some of his church’s foundational tenets. Horton relates an incident where he says to his mother: “I don’t know, this predestination doesn’t make any sense to me. I don’t believe any of this.” She laughs, responding:

“Don’t bother about that, that’s not important, that’s just preachers’ talk. The only thing that’s important is you’ve got to love your neighbor.” She didn’t say “Love God,” she said, “Love your neighbor, that’s all it’s all about.” She had a very simple belief: God is love, and therefore you love your neighbors. (p. 7)

Horton translated his mother’s prescriptions into a practical theology that would serve him for the rest of his life:

I’ve taken this belief of my mother’s and put it on another level but it’s the same idea. It’s the principle of trying to serve people and building a loving world. If you believe that people are of worth, you can’t treat anybody inhumanely, and that means you not only have to love and respect people, but you have to think in terms of building a society that people can profit most from, and that kind of society has to work on the principle of equality. Otherwise, somebody’s going to be left out. (p. 7)

At the encouragement of his church in 1924, young Myles Horton enrolled at Cumberland University in Lebanon, Tennessee. He admits not having had good teachers in his time there, educating himself with “a fairly good library.” Cumberland certainly didn’t prepare him for the rigors of Union Theological in New York City, a radical institution promoting equity and diversity at a time when those qualities were in short supply. In typically humble fashion, Horton explains his reasons for being there:

Union Theological Seminary was considered a very radical place. I was accepted there because they had trouble getting students from the South. Union was trying to break away from the stereotype of all of its students being effete or intellectual. They were looking for people who had been active athletically or done community service or had work experience. I qualified on all counts, but I wasn’t a typical seminary student, I didn’t have the academic background. At that time the intellectual level at Union was extremely high and most of the students had strong academic backgrounds, were from the North, and hardly any of them were poor. (p. 33-34)

Horton assesses the uniqueness of Union and its indelible impact on him and his future as an activist and organizer:

If I hadn’t gone to Union, my world would be much smaller. I wouldn’t have gotten to know faculty and student social activists and become involved in all the issues I didn’t know existed before I left Tennessee. Some of these people came from as far away as China. I remember in 1929 there were brilliant Chinese Communists studying at Columbia University. Their discussions about social change and revolution were analytically sophisticated and showed a conviction and patience that I hadn’t known before. I used to eat them up and then go back to my room and read some more in order to understand what they were talking about. (p. 36)

One of the lasting influences on Horton was Union professor and renowned theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. Famous for his book Moral Man and Immoral Society, Niebuhr, like many intellectuals of the era, was a socialist. People came from all over the world to sit at the master’s feet. One such individual was German moral theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, whose The Cost of Discipleship was published before his hanging by the Nazis for conspiring to assassinate Adolph Hitler. Niebuhr had tried to convince Bonhoeffer to remain in New York, but Bonhoeffer felt a moral compulsion to return to his homeland.

Myles Horton’s next step in his educational journey found him at the University of Chicago. He remarks on the experience:

I learned a lot about social movements, the concepts of how organizations work, while I was at Chicago. I came to realize that things had to be done through organizations. I knew that people as individuals would remain powerless, but if they could get together in organizations, they could have power, provided they used their organizations instead of being used by them. I understood the need for organizations, but I was always afraid of what they did to people. I once wrote something about organizations, saying that they end up in structures and structures become permanent and most of them outlive their usefulness. Later this became important to me when I had to decide what my relationship to the Highlander Folk School should be. Institutions must be kept from becoming oppressive or useless or taking the place of the vitality and life of people. I was very concerned about that relationship of the individual to the organization. (p. 49)

Armed with ideas and a spirit of abiding conviction, Horton returned to the mountains, spending time organizing unions at cotton mills in North Carolina. He attempted to do the same for the textile workers in South Carolina but encountered a roadblock. Although white workers all signed cards petitioning for a union; none of the black workers did. They were distrustful, well aware they were assigned the dirtiest jobs and paid only half of what white people received. Horton understood the futility of a white outsider trying to get black workers on board. He needed to find somebody influential within the community to urge black workers that joining the union was in their best interests. That person was the owner of a local beer joint. Still, Horton didn’t have an easy time of it:

I went to see him but he wasn’t going to talk. His experience was that whites were racist, and that unions had sold people out. And here I was, knowing why blacks hadn’t joined the union, and yet, I wanted them in the union. He wouldn’t talk to me. He just pretended I wasn’t there. Finally I said, “I’m going to tell you the situation. We have 80 percent of the white workers signed up in the union, but we don’t have any black people, as you know. I want you to understand that we’re going to have a union contract that protects all the members of the union. And, if the black people are in the union, that contract’s going to cover them, but if they’re not in the union, they won’t be protected. I understand why you don’t believe me, but you know they have no protection now. But, what you’ve got to think about is that maybe they’ll be treated like anybody else and protected if they join the union, and I’m telling you the truth. One way you’ve got a gambler’s chance of protection, the other way you get nothing. Think it over.”

I told him, “I’ll be sitting under this tree tomorrow, about two o’clock,” and I walked out. At two o’clock the next day, he was there. He walked up and said, “Give me the cards.” He probably still thought I was lying and that they might be sold out, but he was a gambler, and he took the gamble.

I told him we would be ready to go for a contract as soon as he got the cards signed. “And,” I said, “you’re going to have to help us get the best contract we can. We’re going to have a strike, and we’ll need unity and solid support.” And he said, “You just tell us what you want us to do.” The next day he had 100 percent of the black workers signed up. We struck the mill for a week, and the owner agreed to sign a contract. (p. 89-90)

More and more, Horton saw the efficacy of organizing people and resources. He increasingly sought ways to educate people in ways benefitting them. A vision was emerging:

I would like to see a school where young men and women will have close contact with teachers, will learn how to take their place intelligently in a changing world. In a few months, free from credits and examinations, utilizing only such methods as individual requirements called for . . . it is hoped that by a stimulating presentation of material and study of actual situations, the students will be able to make decisions for themselves and act on the basis of an enlightened judgment. (p.56)

In 1932, that vision crystalized into a reality when Myles and two union friends and experienced organizers, Don West and Jim Dombrowski, founded the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee. In the throes of the Great Depression, they focused first on organizing working people and the unemployed. After all, President Franklin Roosevelt had described southern Appalachia as “economic problem number one,” and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt traveled south, witnessing first-hand the deplorable conditions of tenant farmers while detouring to visit Highlander, praising the school for its educational initiative of self-sufficiency. During the remainder of the 1930s and 1940s, Highlander served as the defacto CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations – the second part of AFL-CIO) education center for the region. Important in this time was a general and growing recognition of the power of labor unions to destroy racial barriers and foster inclusivity.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Highlander was an important incubator of the Civil Rights movement. Workshops and training sessions contributed to many of the movement’s initiatives, including the Montgomery bus boycott, the Citizenship Schools (where African Americans were taught to read so they could pass literacy tests required for voting), and the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

For years suspicions that Highlander was a “Communist training school” dogged the center until, in 1961, the state of Tennessee revoked Highlander’s charter, confiscating its land and buildings. The next day, Myles Horton reopened the school as the Highlander Research and Education Center. From 1961 to 1971, it was based in Knoxville; in 1972, it moved to its present location in New Market, Tennessee.

From 1970 to 1990, Highlander agitated on behalf of coal miners and their families. In particular, the center supported anti-strip mining legislation and worker health initiatives. Unfortunately, Horton died in 1990 from brain cancer.

He, more than anyone else, knew the work of Highlander would not end with him. That was not true for other activists during the period. When Martin Luther King was assassinated in 1968, many observers believed that the movement died with the man. Horton never entertained the idea that he was indispensable. As the title of his book suggests, he was in it for the long haul, and he had some specific notions about what that meant.

Your vision will grow, but you will never be able to achieve your goals as you envision them. My vision cannot be achieved by me. You may save the whales, but the dream must push beyond that. It’s a dream which I can’t even dream. Other people will pick it up and go beyond. To put it in a simpler way, I once said that I was going to start out on a life’s work. It had to be big enough to last all my life. And since I didn’t want to have to rethink and start over again, I needed to have a goal that would at least take my lifetime. After making that decision, I never thought of doing anything else, because I knew that I could just hack away on it, and what little I could do would take my lifetime. And even if we had a revolution, the quality of that revolution wouldn’t necessarily be satisfactory, so I’d have to try to make it better. (p. 228)

Postscript – If you would like to receive Highlander’s digital newsletter, go to highlandercenter.org and request one.

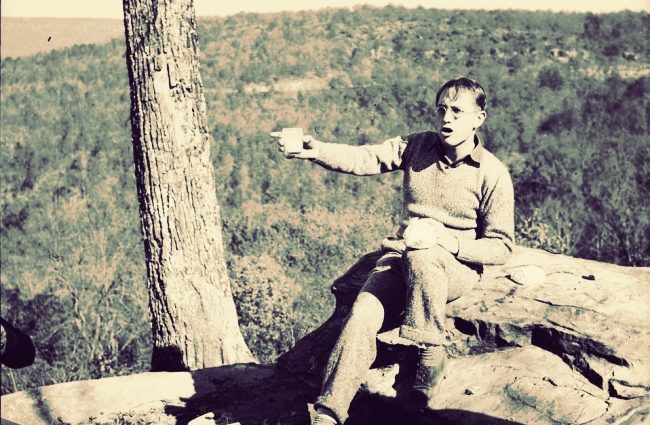

**Featured image of Myles Horton in Monteagle, TN, near Highlander Folk School, 1936-1938 – Swiss National Library – picryl – altered image