Chris Offutt is a Kentucky novelist who lives in Oxford, Mississippi, while teaching in the English department at Ole Miss. He is arguably best known for his memoir, My Father, the Pornographer (Simon and Schuster, 2015).

Offutt describes how his father and mother collaborated in writing pornography in order to put food on the table and braces on young Chris’s teeth:

In the mid-1960’s, Dad purchased several porn novels through the mail. My mother recalls him reading them with disgust – not because of the content, but because of how poorly they were written. He hurled a book across the room and told her he could do better. Mom suggested he do so. According to her, the tipping point for Dad’s full commitment to porn, five years later, was my orthodontic needs. – New York Times Interview

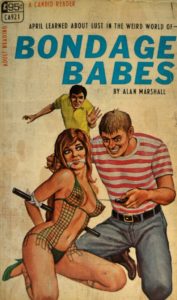

Under 17 pseudonyms, Andrew Jefferson Offutt wrote 400 books. His first published novel was Bondage Babes released by Greenleaf and paying him $600. In the book, someone had murdered a model for a bondage shoot, and the model’s sister was investigating the crime while posing as a model herself.

In his most recent novel, The Killing Hills, Chris Offutt takes up where his father left off – minus the lurid sex scenes. The genre is crime, specifically Appalachian crime, or “holler noir,” inspired by Elmore Leonard’s short story “Fire in the Hole” and the TV series Justified, set in Harlan, Kentucky. Offutt’s book begins with the murder of a woman whose body is found by an old man collecting ginseng: “He was eighty-one years old, the oldest man in the community, the only old man he knew.” Offutt never lets us forget that “the hills are killing us,” in the words of one of his characters. Indeed, Eastern Kentucky is not so much a setting as an unacknowledged character, menacing and merciless to those struggling to survive there. A reader gets the impression that for Offutt’s characters, survival is triumph enough.

The story’s protagonist is Mick Hardin, an army crime investigator home on leave from Afghanistan. His sister Linda, sheriff in the town of Rocksalt, enlists Mick’s aid in solving the murder of the woman whose body was discovered by the ginseng hunter. The plot takes as many turns as a country road. The theme of betrayal is evident when Mick discovers that his wife Peggy is pregnant with another man’s child. He loses himself in Linda’s case so as not to experience the full impact of his failed marriage and his wife’s infidelity. As Mick chases down leads, he’s reminded that revenge is the only motive required by mountain people to shed blood or take a life:

Appalachian people lived by old codes that compelled them to take action. Affronts were always personal. Acts of vengeance maintained themselves for generations. Before school started each morning, Mick had recited the Pledge of Allegiance and the Lord’s Prayer. Every child learned the words: ‘As we forgive those who trespass against us,’ a strong and generous message that neglected to include a timeframe. In the hills it was handier to forgive trespassers after killing them. (188-189)

The Killing Hills is dubbed by Offutt’s publisher as “the first crime novel ever set in the eastern Kentucky hills.” That isn’t so. Elmore  Leonard’s 1969 crime thriller Moonshine War is the story of Son Martin, a Prohibition era bootlegger living in rural Kentucky. In addition to the law, Martin must battle a gang of city slickers seeking to make a fortune in the illicit trade.

Leonard’s 1969 crime thriller Moonshine War is the story of Son Martin, a Prohibition era bootlegger living in rural Kentucky. In addition to the law, Martin must battle a gang of city slickers seeking to make a fortune in the illicit trade.

Offutt’s novel is fast paced and dialogue driven. His style is lean and muscular, except for an occasional figurative flourish. As for his characters, I’m not certain how I’m supposed to feel about them. They don’t lend to easy identification or sympathy. But maybe they aren’t supposed to. Maybe Eastern Kentucky won’t let them be other than who they are. One thing is certain. Offutt grasps the complications and contradictions of mountain culture, as seen in this description of Mick’s grandfather: “Forthright but not forthcoming. Honest but reticent. Watchful but friendly.”

Offutt’s Kentucky drives his writing. With the Bluegrass state’s history of blood feuds, crooked politicians, and a surplus of abandoned mine shafts for stowing bodies, the author may have found a new niche for himself in crime. Of course, genre is irrelevant as long as Offutt observes the one abiding principle of literature that nothing is as it seems.

** Featured image of Johnson County, Kentucky on Wikimedia

Eddie, this was something altogether different. I’d never heard of Chris Offutt, but this quirky memoir and the idea of “holler noir,” peaked my curiosity. I was very careful to search on his name and not a book title with “pornographer” in it, to avoid those mysterious algorithms sure to deluge me for days with x-rated suggestions. I noticed Offut also wrote The Same River Twice: A Memoir, about his own adventurous life off the beaten path. This one also sound like a good read. Thanks for the informative review and for denoting more books to add to my reading list.