I hope everyone has been pleased with this Daugherty series, or, perhaps, been enlightened? My goal has always been to write the facts and let the reader sift through it all. Though admittedly, I may have either ventured into my own opinions or, perhaps, somehow revealed them in my writing. In this series, we have travelled a curious and colorful journey into the lives of Byrd Daugherty, his sons, Fisher and Willie Daugherty, and Daniel Britton Daugherty, including that dreadful day when Byrd and his sons were gunned down by Daniel Britton and Robert Lowe. I hope I have done well to present both sides in a fair manner.

For myself, I think what’s most puzzling in this series is the fact that Daniel and Robert served less than seven years for the murders of Byrd Daugherty and his sons, Fisher and Willie, when they actually received what amounted to life sentences. Their early releases were compliments, in part, of Tennessee’s governor at the time: Henry Hollis Horton. Since time hasn’t allowed me to travel to the bowels of Nashville’s prison records, I’ve snooped around in books, newspapers, and journals from the era. I found a few interesting sidenotes about the justice system during prohibition. I’d like to share those with you and a few of my own theories. Let’s dive into the mason jar again, shall we?

History tells us that mountain people don’t want to be told what they cannot do or cannot have. They get a prickly feeling on the back of the neck. The 18th amendment was a moral commandment, and the longer this moral law continued, the more contentious and deadlier it became. Most mountain people were angry at the government for denying a person’s right to make, transport, sell (and, thereby, consume) moonshine whiskey. An increasing anti-government sentiment became reminiscent of Whiskey Rebellion days. Given that viewpoint, it isn’t surprising that a large number of mountaineers defended moonshiners, bootleggers, and rumrunners. And they had little patience or support for law enforcement. Instead, many people worked themselves into good old frenzied mobs, rescuing prisoners and intimidating—sometimes killing—officers or witnesses. Animosity between the law and mountain folks lingered like a thick Appalachian fog across the valleys. Something was rotten and it had soured people against one another.

The whiskey business was often cutthroat. Some moonshiners built nice little empires, making money by ruthless tactics and blood-stained ways. As a general rule, nobody messed with moonshiners. A person avoided any parts of a mountain—a path, a trail, a stream—where a still was said to be built; except lawmen, of course, who traversed these same parts on the hunt for shine and shiners. But a portion of people, including lawmen, coveted a moonshiner’s success and schemed to take away the man’s (or woman’s – plenty of women were moonshiners in their own right) livelihood in those dangerous times. Their actions caused toxic grudges.

Horace Kephart, in his book Our Southern Highlanders, says

. . . the southern highlander has a long memory. Slights and injuries suffered by one generation have their scars transmitted to sons and grandsons.

The stories that caused all those long memories Kephart mentions are still passed down to this day (i.e., what you’re reading now). But, thank goodness, the hostility incited by them has dissipated over the decades.

After the 18th amendment became law, the government appointed able-bodied persons they thought were all-in for “the cause.” They hired a treasure-trove of prohibition agents/ revenuers who were born, reared, and raised in the mountains. These officers knew a still’s tell-tale signs along the perilous trails and sidewinding roads. Many of these local agents were seen as traitors or bootlickers, and they received a good measure of public coldness and aversion. Some officers weathered through the bitterness and performed their jobs with professionalism. Other officers “used their authority in settling private scores.”1)Our Southern Highlanders by Horace Kephart 1941 New York Macmillan Company These score-settlers kindled bad blood and violent feuds unseen since the Civil War.

In the mountains they do not settle such affairs with fist fights, but with knives or pistols.2)Our Southern Highlanders by Horace Kephart 1941 New York Macmillan Company, p. 241.

Ironically, some moonshiners became revenuers. They knew the ropes, so to speak. Money was tax-free and unrecorded, unless one counts hand-to-pocket as being “recorded.” I have found information suggesting Deputy Byrd Daugherty was once a moonshiner. And some family lore says Byrd’s intent was to own the operations across that particular part of the region. Of course, some moonshiners who became lawmen had no higher aspirations than to be mean as homemade sin. Kephart mentions a man named Hol Rose, a onetime blockader who became a lawman. Rose was a man overflowing with hubris. Kephart said Hol had a “mountaineer’s pride [that] developed to the point of arrogance.”3)Our Southern Highlanders by Horace Kephart 1941 New York Macmillan Company Kephart. p. 241. He was known to search men with a heavy hand—and without a warrant. Moonshiners despised him.

It is a fact that Rose’s methods in searching and seizing were, in some cases, considered high-handed by a large part of the community. It was common talk that he searched men or their belongings, not only without warrant, but with an overbearing manner that was bound to excite bitter feeling and resentment. It was common to hear men say to each other:

‘It wouldn’t surprise me, any day, to hear that Hol Rose had been killed.’4)Our Southern Highlanders by Horace Kephart 1941 New York Macmillan Company Kephart. p. 243.

Indeed, Rose did meet his fate at the end of a gun barrel. To read more about it, click here.

For over a decade, thousands of mountain people were arrested, tried, and jailed. Many of them didn’t go down without some form of resistance. Moonshiners and their customers worked in tandem to promote smear campaigns against an arresting officer. They spread rumors and used “other propaganda” to discredit him. They used coercion tactics to intimidate him. Some skulked around the officer’s home and property; others followed him around town.

For a better picture, we must also look at the Prohibition Era’s justice system. History tells us the entire legal system was as corrupt as the day is long. Prohibition agents were both unethical and “incompetent,” yet they were “the backbone of the federal prohibition forces for most of the 1920s.”5)“Let the Federal Men Raid” by Julien Comte Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, Vol. 77, No. 2. Spring 2010. Penn State University Press pp. 166-192. JSTOR Some law officers milked the system for all it was worth, arresting people for minor offenses. With arrest after arrest, it didn’t take long for jails and prisons to swell until they burst. Even federal prisons couldn’t contain the number. Their prison population had tripled in just six years (1924-1930). Harry Caudill recounts in his book Night Comes to the Cumberlands:

So great was the number that the United States District Judges were compelled to probate most of them, lest the national penal system be overcome by a flood of prisoners which it could not possibly cope with.

To make matters worse, the prison system was mismanaged and crooked. And teetotaler President Hoover’s administration compounded the problem by endorsing “increased prison sentences and fines for prohibition violators.”6)Prohibition’s Greatest Myths: The Distilled Truth About America’s Anti-alcohol Crusade edited by Michael Lewis and Richard F. Hamm. Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press. 2020.

Prisons weren’t the only jampacked entity. As one might expect, courts were also overrun. Judges looked at the staggering numbers of new trials, waiting trials, and backlogged trials, not to mention all the delays, jury selections, sentencings, etc., and realized that dog won’t hunt. Many agents didn’t help matters, either. Judges often had to drop cases because agents were either inexperienced or unlawfully obtained arrests. Judges also accepted countless plea bargains, just to keep the courts from being bottlenecked.

It didn’t take long before the entire court system went soft on liquor charges and convictions. Apparently, they also went soft on murder. According to Kephart, murder was “treated very leniently in mountain courts,”7)Kephart, p. 253 unless the murder was blatant and guilt was evident. Even then, witnesses were coerced, they disappeared, or their stories changed. And, when a man was convicted of murder, he was given a light sentence.

Officers were also among those who were treated leniently. They often shot first and never asked questions later:

But there is also a liberal sprinkling of killings, even as officially recorded, in which the victim, whether guilty or only suspected, was shot when running away.8)“The Death Toll of Enforcement.” James W. Wadsworth Jr. The North American Review, Vol. 229, No. 3. March, 1930. University of Northern Iowa pp. 257-262 JSTOR

Prohibition agents on trial for murder were shown great mercy at the federal and state levels.

So, here we are. We have whirled through mountain folks’ opinions about prohibition. We have examined the prohibition agents and reviewed the prison and legal systems. What about governors? Why, they held the golden ticket: the pardon.

Most governors weren’t all-too-keen on Prohibition in the first place. And they especially didn’t care for the agents enforcing it. A governor walked a tightrope between the dual pathways of law and liquor. Year by year, the rope frayed and the two pathways narrowed. But a governor had political weaponry, and among his arsenal was the pardon.

[Governors] made lavish use of the pardon power and commuted or voided the sentences of hundreds of prisoners.9)Night Comes to the Cumberlands by Harry M. Caudill, 1963 Boston; Little, Brown and Company

Governors were well aware that state prisons didn’t have enough room or money. Plus, Congress couldn’t (or wouldn’t) build new prisons.10)Funny thing is, prisons were built left and right after prohibition. So, a governor felt he “had no other choice but to pardon many of the inmates.”11)Night Comes to the Cumberlands by Harry M. Caudill, 1963 Boston; Little, Brown and Company Prisoners received pardons for the smallest reasons. And a freed man walked smack dab out the prison doors with a full and absolute pardon.

A governor also granted pardons to political backers and supporters. In Appalachia, the person with the most influence was (and still is) the (unspoken) head of a family clan. If the governor performed a favor—like a pardon—he would be well rewarded, not only with votes, but also with loyalty, and just maybe a little mazuma for the coffer.

Most pardons were inspired by political considerations. If a convict had a numerous clan of politically active persons, His Excellency was likely to hear his pardon plea with compassion, but if a prisoner was friendless his prospects were bleak.12)Night Comes to the Cumberlands by Harry M. Caudill, 1963 Boston; Little, Brown and Company

Governors across the nation used their pardon powers to manage issues brought by prohibition. Tennessee was no exception. Let’s introduce ourselves to Tennessee Governor Henry Horton.

Horton worked his way through legislature, first as a representative, then as a state senator. He was a fledgling political bird. He was promoted as governor after his predecessor, Austin Peay, died. Up to then, Horton had about three years of political experience.13)The Knoxville Focus He was reelected for a second term on November 3, 1930. Just four days later, major Tennessee banks—banks that had a hand in his political career—failed, tainting his reputation and ruining him forever.

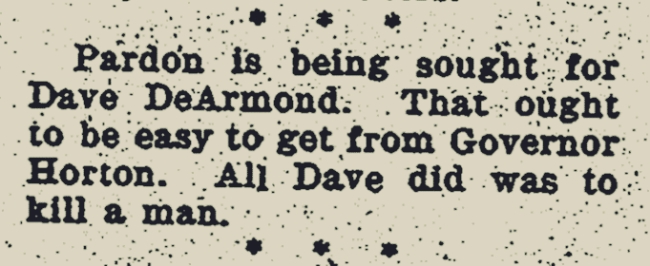

During Horton’s tenure, he signed loads of pardons (though not as many as his predecessor). He pardoned those who committed serious crimes, one being large-scale embezzlement (of up to almost 5 million dollars in today’s money). The number of pardoned murder convictions was surprising. And not just to me, apparently.

Check out a sample of public sentiment in the following dig published in the Knoxville News-Sentinel in 1929:

Governor Horton was an unfortunate politician in an unforgiving era.

How does all this information tie into Daniel Britton Daugherty and Robert Lowe? Let’s see. Shortly after his verdicts, Robert Lowe14)To me, Lowe is the most tragic character in this Daugherty series. I am related to him on the paternal side. My great-great grandfather, Alvis Goodman, married a Parsidia (aka Parzida) Lowe. She and Robert Lowe were cousins. His death was particularly brutal and tragic. I plan to write an article about him within this series. appealed to the state’s supreme court and won. One verdict was overturned, cutting his time in half. He subsequently received a full pardon from Governor Horton, making his total incarceration about 5 years. I found no information suggesting Daniel Britton Daugherty won any appeal. And, while I could find no pardon information, the 1930 U.S. Census lists him as living with his son-in-law. So, he was a free man, at least by 1930.

My theories as to why both men were given early releases are: (1.) they had “connections,” both financially and politically and (2.) they were part of the large swath of prisoners who were pardoned due to prison overpopulation. Let’s take a closer look and dive into finances.

After they were arrested, they were released on bond at $40,000 each. That’s close to $700,000 in today’s money. Many journalists wrote that these backward men had no money and would likely not make bond.

It is not believed that the prisoners can make such large bonds, as few property owners in this part of the country could qualify for such amounts, even were they so disposed.15)The Journal and Tribune. “Slayers of Three Daughertys Win Contention”. April 27, 1922.

But they had money. I have no doubt that Daniel Britton Daugherty had money (and power). He was too dogged a man not to. Knoxville’s The Journal and Tribune mentions that both men made bond. And it appears that Robert Lowe’s mother, who had a substantial amount of money, paid for it all (almost $1,400,000 in today’s money):

Among the signers were Phillip Lowe, Mrs. Hannah Lowe, who is the mother of one of the defendants, Joe Lowe and a man named Bray. The bonds were made in Clinton and the county court clerk of Anderson county certified that the bonds offered would be accepted in Anderson for $80,000. It was reported that Mrs. Lowe owned considerable coal property. (emphasis added)16)The Journal and Tribune, Apr 28, 1922. newspapers.com

With regard to my theories, I tend to side with my research about pardons for votes and loyalty and pardons for overpopulation. We’ve established that Governor Horton pardoned criminals serving time for serious crimes, even murder. Lowe’s mother had bookoos of money. She was likely the head of her family clan at that time. Imagine her influence over the family regarding who to vote for and support: the man who didn’t help their kin or the man who did. (Political loyalty in Appalachia is often generational.) We also examined the judicial system during prohibition and the misuse of power, blatant corruption, and ineptness permeating its every area. The fact is that prisons were overpopulated due to the influx of liquor criminals. The flood of prisoners was perpetuated by the very system who deemed Daniel Britton Daugherty and Robert Lowe guilty. The irony is that they were, essentially, freed by the same system.

Stay tuned for more in our Daugherty series!!

Sources:

All newspapers referenced are from the Library of Congress and Newspapers.com.

- Adams, Lynn G. 1923. “The Police Officer’s Difficulties in Enforcing Liquor Laws.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (Sage Publications, Inc. in association with the American Academy of Political and Social Science) 196-200.

- American Bar Association. 1929. “Why Judges Get Behind in Their Work.” American Bar Assoiation Journal. JSTOR. 371-372.

- Barnett, James D. 1927. “The Grounds of Pardon.” Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology. JSTOR. 490-530.

- Casada, Jim. 2019. “The Murder (?) of Hol Rose.” Blind Pig & the Acorn. July 16.

- Caudill, Harry M. 1963. Night Comes to the Cumberlands. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Comte, Julien. 2010. “Let the Federal Men Raid.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. JSTOR. 166-192.

- Eagles, Charles W. 1986. “Urban-Rural Conflict in the 1920s: A Historiographical Assessment.” The Historian. JSTOR. 26-48.

- Federal Bureau of Prisons. n.d. “Historical Information: A Storied Past.” Federal Bureau of Prisons. Accessed Aug 2023.

- Hacker, Louis M. 1932. “The Rise and Fall of Prohibition.” Current History. JSTOR. 662-672.

- Hamm, Michael Lewis and Richard, ed. 2020. Prohibition’s Greatest Myths: The Distilled Truth about America’s Anti-Alcohol Crusade. LSU Press. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- Hutton, T.R.C. and More. 2011. Blood in the Hills: A History of Violence in Appalachia. Edited by Bruce E. Stewart. University Press of Kentucky.

- Jr., Charles D. Thompson. 2011. Spirits of Just Men: Mountaineers, Liquor Bosses, and Lawmen in the Moonshine Capital of the World. University of Illinois Press.

- Jr., James W. Wadsworth. 1930. “The Death Toll of Enforcement.” The North American Review. JSTOR. 257-262.

- Keith, Jeanette. 2017. “Henry Horton.” Tennessee Encyclopedia. Oct 8.

- Kephart, Horace. 1941. Our Southern Highlanders. New York: Macmillan Company.

- Knoxville Focus

- Knoxville News-Sentinel. 1928. “”Youth Pardoned”.” Knoxville News-Sentinel, June 19: 17.

- —. 1928. Knoxville News-Sentinel, Jan 6: 12.

- —. 1927. “50 Prisoners May be Freed for Christmas: Horton Considers Pardon Applications During Visit at Brushy Mountain.” Knoxville News-Sentinel, Dec 20: 2.

- —. 1928. “Fund Stealer Given Pardon.” Knoxville News-Sentinel, Dec 22: 10.

- —. 1939. “Girl Accuses Man Once Given Pardon.” Knoxville News-Sentinel, Aug 4: 22.

- —. 1928. “Hannah Quits Governor Race.” Knoxville News-Sentinel, May 21: 6.

- —. 1928. “Life Termer Pardoned.” Knoxville News-Sentinel, Nov 4: 12.

- —. 1928. “Pardon Found on Man Slain as Intruder.” Knoxville News-Sentinel, June 11: 14.

- —. 1927. “Rowen Freed by Governor.” Knoxville News-Sentinel, Dec 24: 8.

- —. 1929. “Williams Pardoned.” Knoxville News-Sentinel, March 5: 15.

- Learner, Michael “Unintended Consequences of Prohibition“

- McCarter, H.C. n.d. “Treasury Department Prescription Blank – National Prohibition Act [Prescription, Government document].” The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Accessed July 28, 2023.

- Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law. 1923. “Judicial Decisions on Criminal Law and Procedure.” Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology. JSTOR. 457-465.

- Official U.S. Bulletin. 1919. “Nation-Wide Prohibition Now in U.S. Constitution Declares Proclamation by Acting Secretary Polk.” Official U.S. Bulletin, Jan 29: 1.

- n.d. “Pardon of Tobe Strickland FDR Pardon: Roosevelt, Franklin D. (Franklin Delano) (1882-1945).” American History. Accessed July 28, 2023.

- Pogue, Ernest Morris nd Proince M. 1926. “Some Phases of the Pardoning Power.” American Bar Association Journal 183-190. JSTOR.

- Pridemore, Francis. 1929. “How Doth the Busy Moonshiner!” The North American Review. JSTOR.13-16.

- The Harvard Law Association. 1925. “Availability of Pardons and Commutaions as Means of Conditional Release.” Harvard Law Review. JSTOR. 111-115.

- The White House. n.d. “Herbert Hoover: The 31st President of the United States.” The White House. Accessed Aug 2023.

- The Yale Law Journal. 1924. “Malice Aforethought.” The Yale Law Journal. JSTOR. 528-536.

**Featured image by Image by Zafer from Pixabay

References

| ↑1 | Our Southern Highlanders by Horace Kephart 1941 New York Macmillan Company |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Our Southern Highlanders by Horace Kephart 1941 New York Macmillan Company, p. 241. |

| ↑3 | Our Southern Highlanders by Horace Kephart 1941 New York Macmillan Company Kephart. p. 241. |

| ↑4 | Our Southern Highlanders by Horace Kephart 1941 New York Macmillan Company Kephart. p. 243. |

| ↑5 | “Let the Federal Men Raid” by Julien Comte Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, Vol. 77, No. 2. Spring 2010. Penn State University Press pp. 166-192. JSTOR |

| ↑6 | Prohibition’s Greatest Myths: The Distilled Truth About America’s Anti-alcohol Crusade edited by Michael Lewis and Richard F. Hamm. Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press. 2020. |

| ↑7 | Kephart, p. 253 |

| ↑8 | “The Death Toll of Enforcement.” James W. Wadsworth Jr. The North American Review, Vol. 229, No. 3. March, 1930. University of Northern Iowa pp. 257-262 JSTOR |

| ↑9, ↑11, ↑12 | Night Comes to the Cumberlands by Harry M. Caudill, 1963 Boston; Little, Brown and Company |

| ↑10 | Funny thing is, prisons were built left and right after prohibition. |

| ↑13 | The Knoxville Focus |

| ↑14 | To me, Lowe is the most tragic character in this Daugherty series. I am related to him on the paternal side. My great-great grandfather, Alvis Goodman, married a Parsidia (aka Parzida) Lowe. She and Robert Lowe were cousins. His death was particularly brutal and tragic. I plan to write an article about him within this series. |

| ↑15 | The Journal and Tribune. “Slayers of Three Daughertys Win Contention”. April 27, 1922. |

| ↑16 | The Journal and Tribune, Apr 28, 1922. newspapers.com |

![Tennessee Governor Henry Hollis Horton [1927-1933], 1930 Tennessee Blue Book - Wikimedia_550 sceenh](https://wp-modula.b-cdn.net/spai/q_glossy,ret_img,w_550,h_749/https://www.appalachiabare.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Tennessee-Governor-Henry-Hollis-Horton-1927-1933-1930-Tennessee-Blue-Book-Wikimedia_550-sceenh.jpg)

I am staying tuned!

Yay! Thank you, Peg!