The remarkable Tennessee poet, Danita Dodson, has a new poetry collection titled Between Gone & Everlasting (WIPF & Stock). Appalachia Bare recently sat down with her at Tonya Rea’s Teas and Remedies in Knoxville, Tennessee, to talk about poetry and her new book.

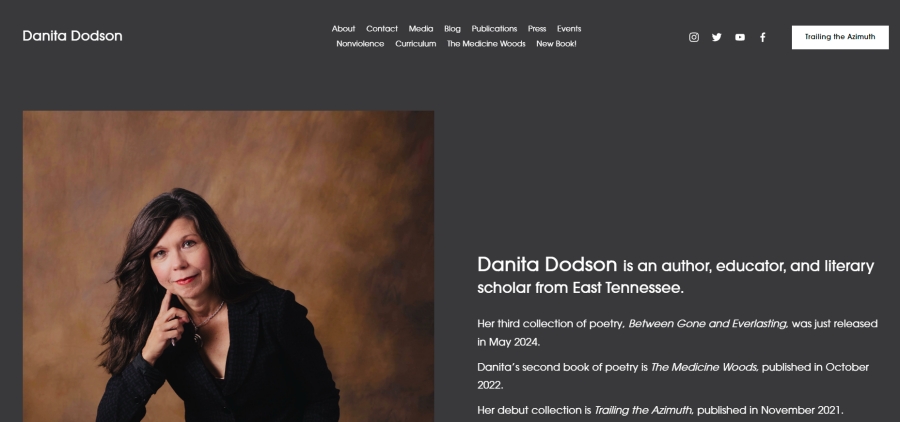

Danita Dodson was born, reared, and raised in the mountains of East Tennessee. Her ancestors have been in Appalachia for centuries. She has published three collections of poetry, Trailing the Azimuth (2021), The Medicine Woods (2022), Between Gone and Everlasting (2024), and is also the co-editor of Teachers Teaching Nonviolence (DIO Press, 2020).

Danita hails a Bachelors, Masters, and Ph.D. in English. She was a “Fulbright-Hays fellow in Turkey, a university professor in Nicaragua, an amateur archaeologist in the Southwest, and a high school Spanish teacher in Appalachia.”1)Taken from Danita Dodson’s bio page She taught composition, literature, and humanities at Walters State Community College. She is now retired and focuses mainly on her writing.

Her deep connection with these Appalachian Mountains is evident in her poetry. Her words encapsulate the very essence of this region – from ancestors to the natural world and in between. Her own mountain spirit and philosophy of interconnectedness flow through her poetry.

So, pull up a chair, have a nice cup of hot tea – or iced tea these days – and join us.

AUDIO

Transcription

AB: So, Appalachia Bare is here with Danita Dotson, who is a remarkable poet. I think she is an Appalachian poet with soul. She really does, um, bring out the love of nature and people and connection. So, but I wanted to start out by saying thank you so much for being here to talk about your work.

DD: It’s an honor to be here. Thank you for inviting me.

AB: So, in your opinion, what is the purpose of poetry?

DD: It’s a good question, and probably one that every poet needs to answer at some point in time. Um, I really think it is to engender connection. One can write a poem from a need to express and to just get something out of the internal landscape.

Um, but it doesn’t stop there. I think every poet wants to be published at some point. So why do we want to be published? Uh, we want to share what we’ve written. And we want to, uh, in some ways, tap into the souls of others when they’re reading, um, so that they can relate to the soul of us as poets.

AB: Yeah. So, does poetry come to you or do you come to poetry like, do you wait for the inspiration to hit or do you search for a topic and then want to write about it?

DD: I think a little of both happens sometimes, but mainly, it’s this burning need, this, this something inside that says, just like a caged bird, just let me out, you know, let me express. So, um, I feel that I let it speak and it may not, it may be broken, it may be, you know, lines or whatever, but there, it happens sometimes at the strangest times. I could be out walking, I could be, you know, well, you know, just doing my daily work and something come to me.

The other part of that is, when I feel like I have something, then I labor over it, and I labor over it, and I labor over it. So, um, in that way, I come to poetry [Yeah.] to make it better, to make it, to make it, um, say everything that I intended to say and sometimes some surprises come. In the process of doing the revision and the laboring, sometimes a poem will take you down a road that you never meant to, thought you would travel.

AB: Yeah, and you can look at it and say, ‘Did I really write that?’ [laughs]

DD: Did I really write that? You know, so, yeah, uh, W. B. Yeats, the great Irish poet talked about automatic writing. He and his wife were really big into that. Uh, and I see that a lot, um, even though poets may not call it that, I think often that something comes from the gut instinct to say what we need to say. And it comes to us in the way it does.

AB: Yeah. Um, your poetry, your poems, have such a graceful appearance on the page. Even, even, if there’s like a stark change up in form, and what I’m thinking of is “The Roundness of Being” from The Medicine Woods and “Butterfly Ancestors” from your current collection. How do you decide a poem’s structure and form?

DD: Wow, that’s a good question. That’s part of that laboring process. And sometimes it is or—it always is organic. I think it happens. But sometimes I will move lines around, like in this current collection, um, the poem, “Cruel April.” That one, I just couldn’t get, you know, I played with the structure several times, and I think finally I’m, when, when on the page it looks to me how I feel it should look.

Um, it depends on the poem though. The poem has to speak to you as for a structure like “The Roundness of Being,” I spoke of roundness and, you know the shape of the earth and this masterful, marvelous planet that we live on, and so I knew I wanted this poem to be round, if I could, which it was hard to even get the type script person on board with that. He had to toy and toy with that to get that perfect. Same thing with “Butterfly Ancestors”—get in that prose poem and just to end on a perfect box where the period was at the end of that justified margin. Yeah, so um, a bit of labor, but I call it a labor of love.

AB: Yeah, yeah. Um, your word mastery and word choices are just amazing. Edward Francisco, um, reviewed your Trailing the Azimuth, your first collection, and he said that, ‘Your words seem endowed with an innate transcendent power.’ You, you also don’t shy away from diction or dialect. Can you discuss the significance of language and word choice in your work?

DD: Yeah, good question. And thanks for the reminder of working with, Ed about—still, that review blesses me that he saw what he saw. Um, yeah, he said, and I felt this, and I’ve borrowed this phrase, that words have energic power. You know, there’s life, this energy, this healing force behind words. And to me, having taught a foreign language, taught Spanish, and taught English, which can feel foreign [chuckles] to any of us sometimes when we’re trying to put words together. The miracle to me is how we take a letter with another letter or groups of letters to form words and those words form phrases and sentences and lines and stanzas and, you know.

To me, if I think about it, in that I could offer, or any poet could offer, you [gestures] as a writer and editor, could offer something unique that’s never been said is a miracle, you know. So, words do have power. Uh, once again, um, I like to look at the poem and the content and the narrator, the story behind it, itself. And then see what words that are new that might be curiosities that, you know, get people to think and stretchin’ in the boundaries of what language is. Um, sometimes I put some foreign words in. [Yeah.] Sometimes, um, I put some scientific words in, as you know, having reviewed The Medicine Woods, I had to put a, a note section in the back for some of, you know, the scientific words that I’d embedded. [Yes]

Um, with, the Between Gone and Everlasting, since I was writing about grief in the heart, then I had to look at emotionally impacted words. So, my play with language was a bit different with each book.

AB: Right, right. So, the next section when we come to—that [previous question segment] was all about poetry itself, and the next section is about you as a poet. Can you remember the first poem you ever wrote?

DD: Wow. I know it goes back a ways. The first poem I ever read was in first grade, it’s still with me, Robert Frost’s “The Pasture.” Uh, imagine that. And I was hooked. I knew that I was going to study poetry and literature all the way to college. And I started toyin’ with writing at a young age. But I really think it was high school that I can remember. I still have the notebooks, um, as far as my paper trail of writing poetry. I really think it, it’s maybe my freshman year in high school. Although, maybe I was carrying inside some poems, and I had that desire to be a poet. [Yeah] It just happened, you know, in God’s timing, but I had my first poem published when I was a senior in high school in a literary magazine.

AB: Oh, that’s wonderful.

DD: Yeah, and I should have paid attention then, you know, I got too busy with life. But I think as a child, hang on to your dreams, ‘cause I think the universe is trying to tell you something.

AB: Yes, yes, and that message will continue to be told. [both laugh]

DD: And you can’t run from it sooner or later, you know. It catches back up, and it stands right in front of you and says, ‘Write, do me.’

AB: Yeah, a part of who you are. So, uh, do you prefer to write by hand or computer, or do you use your phone, or all three?

DD: Um, all, well, not my phone. [laughs] I’ll take that one out. Uh, usually never my phone, because if, if I have my phone with me, I try not, I consider it a distraction for, you know, [yeah] in the first place. Uh, I’m sure if that’s the only thing I had and the words came and I couldn’t carry them back with me or couldn’t find paper or my computer, I might go into notepad and write something down. But, um, I do carry notepads with me occasionally. I want to get better at that as a poet, but most often the words come to me when I’m in motion.

AB: Yeah.

DD: Um, I may be on the trail. I may, like I said, be doing housework or garden work. And often I just carry that essence with me till I get to a space where I feel like I can write them down.

My computer is just a comfortable place, you know. I know how Hemingway felt with a computer. [Right.] Or Faulkner, or we have, or typewriter, excuse me. Um, you know, there’s something about clicking your fingers to keys, and seeing black words on a white space to feel like something is materializing, and since I’ve read so much, just seeing something in print, um, it engenders and nurtures the creation process.

AB: Um, let’s see. How—is there a time as you’re writing a poem that you know when a poem is finished?

DD: That’s a good question. Um, it may be an individual process with each poem. But yes, I do know there’s a time.

Um, there are some poems I’ve written and had just very few passes or revisions where I felt it was, you know, out the gate, ready to go. That happens seldom, though, the process. It’s usually labored. And I will tell you with all three of my books, uh, some poems were re-found that I had some from a while back.

Like I even have a poem, uh, about my father that I reworked, that I had written in this collection, that I had written about him in high school. It, it was totally reformed from my adult vision at this point in time. But, um, hang on to everything, you know, because you never know [Yeah.] how somethin’—So, sometimes things will marinate for a month or years. And, and then, but generally, and the hardest part is letting go and sending the final manuscript off to the editor. [chuckles]

AB: I wondered about that. That has to be—because it’s your baby. [both laugh]

DD: It’s your baby. You’re just saying, okay, now can she walk? Did she learned enough steps to walk out the door into the world?

And, uh, letting go is tough sometimes. Um, and so I try to get it, before I send it off, as the final manuscript. I try to get it just as perfect as I know. And then when the editor asks me, ‘What’s the time frame? We’ll work with you about when you think you’ll have the manuscript in our hands,’ I still have to rethink, you know, when am I going to be done? And I always give myself a large window of time, [laughs] and use almost all of it, you know, to do the revising. Um, but, um, yeah. Then when the manuscript comes back to me in the typescript form, it’s a given that I just, you know, tweak any typos or if I, there’s a blaring word that doesn’t fit that I want to change, but I know pretty much when I say, ‘Here it is,’ you know, I’ve got to let go. [Yeah.] And then I feel like it, like now, when I see these books in print, I don’t feel a need to go back in and be an editor of it. And getting to that point feels pretty good.

AB: Yeah, yeah. That is, that’s wonderful. [Chuckles] Um, your love and honor and connection with ancestors is what I think I’ve mentioned in, um, I think it’s The Medicine Woods [review] where it’s all woven throughout all of your books. And, going back to Edward Francisco again, he said that, your poetry, of one of many things, functions to ensure that people and our memories are kept alive. Um, can you talk about your Appalachian heritage, including your ancestors, and the upbringing that you had? How did it influence your poet poetic voice or style?

DD: Wow, that’s a good question and it’s an important one ’cause I feel that, and that others see that essence coming from people like you and Ed to know that you see that. [Yeah.] Uh, gives me hope that others will see that in my work, even if they don’t know what it’s like to be an Appalachian.

They know what it’s like to be human. And I had a, uh, I did a poetry reading in Wise, Virginia, and a professor was there at the reading, and she was of Japanese heritage. She was an English professor, though. And she said, um, you know, ‘This is not of my culture, but that you are so connected to your own heritage and your own culture still makes it feel like mine.’

And to me that was the largest compliment, because to her, being human is being able to be as connected as you can to who you are and, you know, where you came from and why you were put in the place and space you were on the planet. But, uh, yeah, I feel fortunate. I had an upbringing that was grounded and secure.

My, my father—actually, um, my mother’s parents, but especially my father’s parents—came from, you know, impoverished circumstances in the Great Depression. Uh, and they talked to me, you know, pretty honestly about what it was like to struggle in the hills of Appalachia and what it was like to, uh, be a kid like me growing up, that, you know, and maybe havin’ more than they did when they were young, uh, and to never take that for granted; and engender compassion, maybe with classmates that I had who weren’t as fortunate. And my father was, and I’ve written a poem in this collection, a welfare worker. Spent forty years from the inception of the program back in the 60s [Oh, wow.] until the year 2000. So, he saw need in the community, and, not that there’s not need in the world, but he understood that part of that, you know, bein’ Appalachian is to struggle. Right? And that you always need to have a sense to give back. Um, but that there is strength in the struggle. And my granny, who I write about a lot, that you actually connected to some of my granny poems. I actually have just churned out three new granny poems.

My mamaw—I should call ’em Mamaw poems. I, she knew that she struggled, um, maybe financially and in other ways. Um, but she lived richly. She went to the woods, you know, she’s drinking these teas like we’re drinking today, you know, and thanking God that the earth provides. Uh, and my, her husband, my grandfather, was a minister and was rooted in the scriptural, I guess, mandates to love your fellow human. And, uh, I just count all that a blessing to have had that upbringing.

Um, but, the roots in the land, too, that’s another thing that I learned from my father and his ancestors before, and I, as you said, I’ve written about this, is that the land itself holds memories. It holds footsteps. It holds pathways where people have been, and I’ve been blessed, um, for seven generations for my ancestors to walk the same territory. [Oh my gosh.] And I now own two pieces of those, you know, of the land and I’m now not takin’ that lightly. And I’ve written about that in the “Maps of Home” section of the new book, is that, you know, you watch those old spaces grow up in weeds and whatever. You see them not what they were before. But you still know people walked there. [Yes.] So slowly and surely, I’m hiring people to groom the land and to help me return it to what my father and my grandparents would have remembered.

AB: Yeah. Well that’s wonderful. Yeah, I have always felt that too, that walking on the footsteps of people who were before me and, I don’t know, my mind’s eye goes to, um, even Native Americans. [Oh, yes.] Walking, you know, walking along that way, too. [Oh, yes.] What do you think is the most challenging aspect of writing poetry?

DD: Wow, that’s a good question. And I should have expected it. [laughs] Uh, I think it’s a, allowing yourself the, well maybe this is a blessing too, but allowing yourself those hiatuses, those holding zones, those spaces where you don’t feel creativity is happening. And to realize that it’s okay, you know. And to face that someday, you know, look at the computer, it’s like looking in the mirror. [Laughs] Or looking at your notepad, and if you’re saying, you know, I’m filling this something inside, but why, why doesn’t it materialize? And I think you have to just let go and allow it in time.

AB: Yeah. I’ve heard that, um, like ‘refilling the well.’

DD: Oh, I love that.

AB: Yeah. So, you have to have water. [laughs]

DD: You have to have water. You, you write so frequently, so I can’t imagine—I think it’s getting into a practice, too, as well, isn’t it?

AB: Yeah, yeah, it is.

DD: I was in a workshop with the great Jane Hicks, who wrote a blurb for my new book, one of Appalachia’s greatest gifts as a poet. But she said, this was just last week, that talking to fellow poets in the group, published poets, and she said that, uh, don’t just, you know, put a definition on what writing is.

It doesn’t always mean that you’re literally putting, uh, ink to page. Uh, it can be that you’re just thinking about it, you know. You’ve got a kernel up there that’s marinating. Could be that you’re researching something. [Right, yes.] And I do a lot of that, and I know you too. [Yes.] So, I thought, ‘Way to go! Now, I write every day.” [both laugh]

AB: So, um, you have said that you were first introduced to poetry as, uh, via Shakespeare and Robert Frost, specifically you mentioned “The Pasture.” Um, you mentioned other influences, and I’ll just name them off here a little: T. S. Eliot, Joy Harjo, Wendell Berry, W. B. Yeats, Rumi, Langston Hughes, some Southern Appalachian poets, Rita Sims Quillen, and Jane Hicks. And then you mentioned fiction writers like Toni Morrison, Lee Smith, and Amy Greene. How do you think these influences have affected your voice or style as a poet?

DD: Wow. And I should throw Mary Oliver in there too. [chuckles] Um, I think the diversity of all those voices there that you have seen in my lineup, uh, allows me to know that little East Tennessee girl with my own diverse voice, you know, even with Melungeon heritage, uh, that what I write can matter too. And I think that’s one way that, you know, from Shakespeare to Toni Morrison, that’s quite the gamut, isn’t it?

[Yeah, yeah.] But, um, also in content and the way they write. I love Berry and Harjo and Oliver, the, you know, the nature, and Frost, and that was what I first loved, and those poets, uh, they allowed me to know that the great outdoors is just as nice to write about as some, you know, grand building, you know. [Yeah.]

And those spaces don’t have barriers, right? There, you know, the landscape belongs to everyone. So, I love reading even in novels about the landscape. And there’s also the internal landscape, you know, great writers like Toni Morrison and, uh, Amy Greene, who is I think another gift as a novelist to Appalachia, are able to see how the internal landscape of women particularly, and their stories [Yes.] that beg to be expressed, I think gives me courage as a woman to speak what I have to speak.

AB: Yeah. Um, do you have influences outside of literature? Like, I know your travels, music maybe, or films that inspire your poetry?

DD: That’s a good question too. Because I think poets work with images and we, even though we love to read images and imagery in other poets’ writings, um, sometimes we have to literally be attached to visuals and auditory. I mean, I think that empowers the way we write. Um, I am not a trained musician, but I grew up singin’ in church and was, you know, trained by my father and his father before, even my grandfather, to love old-style, stripped-down Americana folk music and gospel music that comes out of mountain churches.

So, I think that has a, the musicality, uh, of my poetry, I think comes through. And that, if I labor some with line, you know, getting the lines right in some of my poems, a lot of that is ‘cause I’m, doing the iambic pentameter, I’m beatin’ out a line until I get a word or an image that fits. And it doesn’t always have to happen that way in every poem. Um, but I, I think there’s some musicality, some of that influence that comes in.

Um, you mentioned film. I like to watch movies, but not so much as like, I like to see great art. So, the ekphrastic—There’s a word for you—the ekphrastic experience in poetry is, you know, taking a painting and writing words to go with it. [Yes.] So, I have done one with my favorite painting, I guess, of all time, is Salvador Dali’s Persistence of Memory. It’s in this new collection where, um, I’m actually talking about an Appalachian landscape, you know. I’m talking about seein’ the wasteland that could be left behind, which Dali paints. Uh, but he also paints the mountains and he paints this hope of remembering, uh, and at least that’s what I see in that. [Yeah.] And so that led me to Molten Hills and, uh, “Molten Clocks and Undying Hills.” So, I do a lot. Painting is a big influence.

I won’t stop there though. Uh, photographs. Sometimes my own photographs, or other photographs I see. And I know you include a lot of beautiful photographs with your, uh, writing pieces. So, a picture paints a thousand words? [Yeah.] It really often does.

AB: Yeah, it does. It really does. It’s pretty amazing. Because, I mean, you could come back to the same picture the next day and it would be different. [giggles]

DD: Oh yeah, yeah. So that’s what I did with the Dali painting is, you know, and I, and I’ve looked at it, I’ve studied it all my life, and then now looking at it through the lens of grief, almost with, I actually literally got my print out of the piece, you know, the copy of the piece and took a magnifying glass [laughs] and saw things I hadn’t seen in all those decades before, so, yeah.

I think if you write a poem, and that’s a good, um, exercise for anybody who wants to write poetry. If you write a poem based on a painting or a photograph, do what you just said. Allow yourself to come back to it, you know. [Yeah, yeah.] See that bee on that flower you didn’t see the first time around.

AB: Right, yeah. Um, so do you have an ideal time of day or writing environment that stirs your creativity? Like, Black Atticus said that, um, he liked heights. And heights did it for him. Edward Francisco, he mentioned that four a. m. at his desk. So . . .

DD: Um, it is organic, I’d say, fueled by the passion of the moment of if something comes, you know, to me. But I do get a good feeling after breakfast every morning to go to my computer and sit down and see what materializes. And it could be, like I’ve been working on these three Mamaw poems I told you about. And, uh, now they’re already takin’ form. They’re already, you know, taking flight as far as wording.

I’m still laboring over them. Um, so I may sit down every morning and work at that. Or I might do like Jane Hicks said, you know, I might be researching. I’m working on a novel as well. [Oh, wow.] Well, I’ve been working on it for two or three years, so it’s probably going to be another thirteen years. [laughing] But, so as a, someone who taught every morning for 33 years, I was used to, you know, having that morning time to be in my element teaching.

So, I think bringing that kind of energy to writing, that’s probably my best time of day. After dinner or supper at night, um, I also like to sit down and I don’t like to be on my computer because it’s not good for, you know, promoting, it does not promote good sleep. But if I, sometimes between the hour of seven and eight, I will write. Um, but any other time in between. [Yeah.] [laughing]

AB: Um, well you’ve talked a little bit about your future projects, that you’re working on a novel and, um, your three Mamaw poems. Yeah. And is there anything else you’d like to share you’re working on, or . . .?

DD: Uh, yes. I actually was invited a couple of days ago to, since I’ve done work in nonviolence, I edited a book, Teachers Teaching Nonviolence, and I’ve written about nonviolence in The Medicine Woods, and nonviolence toward the earth, and how we treat the earth is how we treat humans. It’s all together, you know, being kind to everything that has being, everything that lives. So, I have a network of academics, who are dealing with nonviolent education. And in this day and age, you know, uh, we need to teach the young more about the spirit of nonviolence, which, you know, guns are out there and such a, such a heavy burden for young people, you know, the spirit of meanness that’s around in our country [Yeah.] and the violence with words.

And the violence in, you know, we see in Israel and Palestine. It’s everywhere we look; we can’t hide it. So, I’ve been asked to write something for a new book that’s coming out. And I was asked, weirdly enough—imagine a group of academics coming to me and saying, will you write some poetry about nonviolence?

AB: Wonderful! Oh, that’s great!

DD: And you can do an academic paper about, you know, maybe, um, tapping into the maternal spirit, you know, what do women have to teach us about how to better promote nonviolence. You can do an academic article, but we’d really like for you to infuse the spirit of poetry into this new book. So, um, I’ve got to November to get a draft.

AB: Yeah?

DD: But I, I trust that they feel that I can weave together some of the things that I’ve been doing already in my poetry. [Yeah.] So, I, I think that that is a unique experience as a poet.

AB: Yeah. That’s wonderful. So, we mentioned, um, your, your books here. Um, you have three—I, I just, I can’t even praise your poetry enough. I just love it so much.

DD: Thank you.

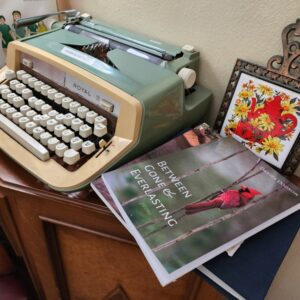

AB: Um, you have three collections. The first two, uh, Trailing the Azimuth, that was in 2021. And The Medicine Woods, 2022. And your newest collection is Between Gone and Everlasting. And it was released in April of this year. And all three of these books were published by WIPF & Stock, right?

DD: Right. Yeah, WIPF [pronounced “Wiph”] & Stock.

AB: WIPF in stock. I wanted to know if you could talk about your most recent book. And what was, first of all, what was your inspiration? And how it differs from the other. I know you had mentioned that you’re, it, it was a way to help with grief.

DD: Mm hmm. So, uh, yeah, the origin of that, I was finishing up The Medicine Woods as a project when my father suddenly passed, April of 2022, and um, I knew the editor would give me just a little, a lot of space to get that, that book together because I wasn’t in a right head space.

Um, but I felt the need in that to write a poem, remember my last hike with my father, and I put that in the ‘Keeper’s’ Collection, or um, section of The Medicine Woods, the poem called “One Last Mountain.” And, so that was dedicated to my father. So, I put poetry writing aside. I got that project and just, you know, released it to the world.

And I dealt with trying to heal the best I could. And I would tell you it’s harrowing. Every experience with grief is its own individual. It has its own individual, individuality. It’s almost like a human being itself. Grief, that grief, you can give it a name with a capital G. You just have, well, you can make a choice to ignore it or you can, you can sit with it. I just like draw a chair up, you know, personify and just say, come sit with me. Talk to me about, how do I need to get through, how can I do this, get through this? My father was my hero. [Yeah.] And I know he lived this ripe 85.7 years, um, and talked about, he knew, even though he was not ill, but his time on earth was not to be very long.

But still, you know, I just grew up seeing this person who hung the moon. [Yeah.] And, uh, I don’t think I prepared myself that it would happen anytime soon, until the evening, in the gloaming. Uh, that I found him, uh, and, and he was gone, you know. So that word “gone” bore with me a lot. And I will, occasionally, something so . . . raw spoke to me in words.

And they were often jumbles of words and phrases, but occasionally, uh, and it would happen often when I would be sittin’, or walkin’, or just, you know, just trying to be in that space to allow the grief to speak to me. And I started putting a few things on computer, and then just put it aside. And then, uh, something that he said to me a week or two before he passed spoke to me. And I remember him looking at me and smiling and saying that, ‘You are a poet. You’re a great poet. Uh, I got an idea. If you want to tell a story. Talk about this, this little boy that was born in the backwoods in a holler, dirt poor, who went on to somehow make it through college.’ Uh, and he went on and on, you know, because he was looking, I think at that point in time, he was looking back on his life in ways that I didn’t realize then and saying, ‘I’ve been so richly blessed.’ [Yeah.] But write about me, in essence. And so, I said, well, I will, ‘cause I was working on a family history book that went back 200 years of my ancestors. And I said, ‘Well, Daddy, we are coming to the point where I’m ready to write your chapter.’ Literally. You know, I’m ready to tell your history. And he was excited about that.

So when I wrote his obituary, I thought, wow, that’s an abridged version of his story—his history—and so I got to work writing, you know, from almost, I won’t say an academic, but from a very organized way. I thought, I’m going to organize my grief, and I’m just going to write biographically about my father in the third person, [chuckles] [Yeah.] and I’m going to find snippets of things, because I was going through his files, and I found all the evaluations of his time as a social worker. [Oh, yeah. Oh my gosh.] He had kept all those decades and things, nice few things people got to say about him. Um, I had cards that people had sent him. I had recordings and videotapes of him singing. And, so suddenly after I wrote that up, because I wanted his grandchildren to, and his great grandchildren, to have that, the poems started coming.

And I didn’t force it. [Yeah.] So suddenly, while I was writing something, I was opening up a separate word file and carrying some of those phrases from that biography into that. And that’s how Gone and Everlasting started to mature. And then the title came. I was sitting, I had read a, someone had posted on Facebook, of all places, I found an article that a friend of mine who’d lost her mother and that psychic pain that you deal with during grief.

And somewhere in there, there was a phrase about the ever—they’re not just gone, we’ll see them in the ever, in the everlasting. And then I got to think that somehow, we’re really sort of in between, you know, where, where we, we don’t, we can’t see them totally as they were in the past. We can’t yet see them as they are in the everlasting. We know they were there. We know they are there. We’re in this umbral space, this threshold, this, this shadow world where we cry and where we mourn and where we love and where we know them. And it seems like every object we find sparks a memory that somehow brings them back. And I just, to me, it, in the midst of grief, it just felt like a miracle.

And I count my blessings that I was able to write this and they chose a red bird, I didn’t do that, on the cover, and I feel like this piece of poetry is much like the red bird. I can have conversations with my father, I have had. And I’m sharing him today with you, and then whoever hears this interview and it’s somewhere in between that space of being gone and the everlasting. A long answer, I’m sorry.

AB: No, no, no, really. I mean, I kept thinkin’, uh, well, one of the things that I had wanted to ask was, in a prior interview you revealed that poetry nurtured your, nurtured you and likely it still does, through the grief process. Uh, you also, a part of the meaning of the title, saying on most days “we, the bereaved perhaps linger somewhere between two poles of being, between where we mourn the gone and where we celebrate the everlasting.” And then I see you, you talk about the umbral space there. And I immediately my mind went to a liminal space.

DD: Oh, yeah.

AB: That it’s between, it is between. Um, so when you were talking about that, and then you said it was a long answer, I was very grateful for that because I love it. Um, was, so you talked about the particular point where you realized the in between space. Have you always known, maybe it’s in the back of your head, that there is that in between space? And your father’s passing made it a deeper part of you?

DD: Ah, that’s a good question. And it’s a deep question. Um, yes. I think looking back, and thanks for putting that into words. I’m going to call it a thin place, uh, which also means that, um, that space allows heaven and earth to meet. And I’ve always known it’s there. And I’ve always known it’s something from the spirit world can visit us in that umbral space if we sit quietly [Yes.] and allow it. Um, something greater, uh, than ourselves, you know. And we’re so busy in this world. Uh, but, but the Scotch Irish knew it. The Irish knew it. The old, the people of the old world knew it. You know, our ancestors [Yes.] and a lot of the old Appalachian men and women, they, they allowed themselves, I had a great grandmother. I remember my grandmother telling me about her going to the woods and people could hear her from all around prayin’. [Oh, wow.]

But she had a, she had a space where she was grounded to the earth and was mourning things that were gone. You know, you could hear her echoes and her cries. Uh, but she found words in that space to somehow bring the everlasting in there. And I think I have always been aware of that. And I think, uh, I will be more aware from here on. And I think creating this book allows me to, in some ways, be more present for those magical moments of when, um, something is given to us [Yeah.] from a loved one from beyond.

AB: Yeah. Yeah. I, I mean, I totally get that myself. Yeah. I feel like there are messages everywhere if we, if we just look.

DD: Yeah.

AB: Um, would you mind reading a poem from your newest collection?

DD: I will. Um, I’ve bordered upon the teary eyed today and I knew better than to read right now, and [it] be a poem that would make me break down here as I’m being recorded. But it’s okay if I did. [Yes.] Um, but Father’s Day is coming up. You know? And I think this is so appropriate, Delonda, that here we are, three days before Father’s Day, and I’m getting to share, a little bit about my father, uh, with the world.

But I’m going to read a poem called “Clarence’s Counsels.” My father’s name was Alfred Clarence. Um, and there’s some humor in here, too, but I think in many ways this, because this is his voice, getting able—so some of the poems that I’ve written, I have written in third person, through a window, looking at him at different stages of life, even that last day, you know, when, when he took that last walk from the barn to the house and died somewhere in between.

Um, and then, then there’s one where I have a, an ekphrastic interview with a portrait of him as a little child. You know, so I’ve written sort of narratives there. But this one, and there’s a couple of poems where I’ve written in the first person from his voice, so this one is my father speaking all those things that, you know, dads tell us to do for our betterment. [chuckles]

“Clarence’s Counsels”

Don’t run more water than you need.

Keep your shoes till they’re worn out.

Or if you see someone who needs them

more than you do, give them away.

Phone me the minute that you get there.

Be cautious of the strangers you meet.

Be kind, but don’t trust them outright.

Knowing someone well takes much time.

A thing does not happen simply because

we have anything much to do with it.

If the good Lord wills, it will.

So always believe that something larger guides you.

Go to church each time the doors are open,

and offer your heart and community there.

Practice a song before you rise to sing it,

knowing its curves, tones, and blessings.

Keep the peace with everyone, even if

you don’t agree with what they say or do.

Never raise your voice in anger.

Being a peacemaker is the Lord’s greatest calling.

When you have enjoyed a wonderful day

and do something beautiful that brings

your heart light, say out loud, This is living!

Time is short, and we’ll all travel on soon.

AB: It’s beautiful.

DD: I did get a little teary eyed there.

AB: Well, I mean, yeah.

DD: Well, now that I read this poem again, I see the spirit of nonviolence has been inherited.

AB: Yes. Um, on the deep side, that’s, that’s [the section] where we’ve come to now. [Okay.] How do you hope your body of work will be remembered in the future?

DD: Oh, my goodness. Uh, this might make me the teary eyed of all to know that we can be immortal and we can live on in those energic spaces of words, uh, and having an interview like this, it’s going to be out there, uh, is a testimony to the fact that I am sharing myself with the world, even in a way, when I am gone, uh, like my father, that something of me is left behind.

Because my worry was, uh, what will be remembered about me? What has been, you know, as I grow older, deal with osteoporosis and [chuckles] all those other things, you know, knowing dealing with old age, which I’ve written about, is, you know, losing someone and facin’ your own mortality through that process makes you wonder what will I leave behind? What’s the world going to remember about me? Will I be so graced to leave memories that bear upon somebody’s heart like my father’s does upon mine? And, uh, I just hope the world remembers me through these poems as someone who is present, and I think that’s a good, important element in a poem, the most important element, is that there’s a presence and honesty and integrity of whatever it is that I express that, um, that it’s palpable enough that people see it. It has its own heart, [Yeah.] and therefore when I’m gone, it’s still beating everlasting.

AB: Yeah, I see that. Well, you have done, you have certainly influenced me in that way. [chuckles]

DD: Well, likewise. Likewise, Delonda.

AB: What do you think are the most important habits or behaviors for an aspiring poet to develop?

DD: Most important habits or behaviors. Um, I would think we’ve talked a lot about your question about finding space to write. [Yeah.]

And even though mine sometimes is all over the place, I think finding something that has a sort of normality, a grounding spot, wherever that grounding spot is, to nurture yourself through the process. Now this might not be the origin of the art, of the piece of writing may not happen in that space, but it’s a space, it’s like a home you can return to.

And so, like we’re drinking our mushroom cocoa here today, you know, you might have something that nurtures you, something to surround it in that space, surround yourself by some of your favorite things. I once heard Dolly Parton, and who doesn’t love Dolly? I’m in Knoxville. [both laugh] I once heard Dolly Parton say something that hasn’t left me. She said, someone had asked her a similar question, and she said, on her tour bus, now she’s working from home all the time, you know, and I know this isn’t happening at her home, but she creates an altar, a little space that might, she might have her burning candles, she has her notepad, where she can pray and be and write.

Uh, so, I would say create whatever that little altar is, that little nurturing space, that you can come home to, where you may create your writing, or, you bring your writing there. Uh, like an old friend that you want to introduce to your mom or whatever, because that’s what I do. I don’t often do my creation in that space. Like I said, some of the greatest moments happen when I’m on the trail. One of the poems that still bears, well phrases that bears with me in a poem, is “The Quilted Hills.” It was just a little line that I even borrowed from my own poem into another poem. But that happened when I was just walking through the woods seeing the autumn leaves. [Yeah.]

Uh, and then I just carried that phrase home with me to my sacred space and wrote about it, so that would be one piece of advice. The other is don’t give up if you have a dream. You know, if you feel that you’re a poet or a songwriter, or a novelist, don’t give up on the dream. It does, there’s no expiration date on dreams. [Yeah.]

I am proof in that because I was lured to poetry as a youngster, as we’ve talked about. I published my first poetry as a senior in high school, um, published some poetry in college, and then got so busy teaching poetry, pursuing degrees after degrees, I just sort of let that creative part of me, uh, go aside. And I apologized by just saying, okay, I’m teaching others to be creative. But when the pandemic hit, [Yeah.] I was, you know, I was working from home. I was pointblank in my best, safest nurturing space. And the creativity started happening. And I thought it’s time to retire. [chuckles] It’s time to write, um, because you promised a little girl a long time ago, a little 10-year-old self, that you would write. So that is a long way around to say create a nurturing space and, um, know that your dreams of being a writer, they don’t have a time, uh, factor on them.

AB: That is so true. I mean, it really is and you don’t know where, once you realize that dream or it’s in the process of happening. [Yeah.]

You don’t know how many great places it’s going to take you, [Yeah.] or how many wonderful people you’re going to meet, [Oh, wow.] or like-minded as far as literature, and, I don’t know, I always tell people that’s where I fit in most is with writers, ‘cause everywhere else I just don’t fit in.

DD: I know what you mean.

AB: Oh my gosh, yeah.

DD: I got away with it for years. My students would say, it’s okay to be eccentric. You’re an English teacher. [both laugh] You know, you studied English. But I’m the same way. I feel at home with a group of, you know, writers that avant garde, lateral-thinking and talking and . . .

AB: Yes. Yeah. You have so much in common. Yes. Um, well, we’re, we’re coming toward the end here, but I wanted to ask you, where can readers find your books?

DD: Well, I’m out there in many places. I, uh, you, you can go, first of all, to my website, danitadotson.com and can click on the links to the books.

There’s a section for books, but on the home landing page, um, I have all three books up and you click on there. You can just go to Amazon. A lot of people shop that way. You know, you can go to Amazon, um, you can go to my publisher, WIPF & Stock [Yes.] as well, uh, Barnes and Noble Online, Ingram, um, Bookshop, IndieBound, or brick-and-mortar books like, uh, Union Avenue. I’m scheduled to do, they have my other two books and we’ll have this one in very shortly. Um, I’m doing a reading there in October. So, I will get the word out there, uh, too. And you can just ask a bookstore. I mean, I am all about, uh, visiting good independent bookstores. You can ask them to order my book. Or you can come to one of my readings and there is an event page, a section on my, uh, website.

AB: And, um, where can people find you online or on social media?

DD: Yeah, well, again, my website is, uh, danitadotson.com but on social media, you can find me Facebook, There’s Danita Dotson. I have, I have an individual account, but um, Danita Dotson slash author is my author page, which is preferable. Um, that way you, you don’t have to do anything. You don’t have to bypass. You can just, uh, click on that and, and like the page and, and follow me. Uh, on Instagram, Danita Dotson. Yeah. I’m also on ThreadX, uh, as well.

AB: But, um, one of the things I wanted to say is that when I was reading your Between Gone and Everlasting, the latest collection, it, um, it dawned on me that sometimes the poems seem to become the parent who listens and comforts. I mean, when I was reading it, I just felt enveloped with so much, um, so much love and always in your, in your poems, connection, a connection to everything. And it doesn’t have to be, I mean, you write about a dragonfly, you know, it doesn’t have, the soil; there is a connection to people who we can’t see, who may not be here in our, with our eyes, you know.

And the other thing is, I wanted to say that, as a whole, your collections tell the reader that life is a journey. Whether you’re Trailing the Azimuth, trekking through The Medicine Woods, or journeying with that liminal space Between Gone and Everlasting. And, and it, that’s true whether you’re connecting with people or nature or history or grief or anything. And I just wanted to say thank you for your poetry and thank you for taking your readers on a wonderful, mystical journey through Appalachia and beyond and all the other places that you’ve encountered and people. So I wanted to say thank you.

DD: Oh, you’re welcome. It’s my pleasure and my honor for—those words are so beautiful that, to be remembered, that is how I want to be remembered. That my poems speak that. And, uh, how lovely, everything.

AB: Yeah, and, um, so I think we’ve reached the end of our, our interview, but I did want to say thank you to Tonya Rea’s. They are a tea and remedy shop in Knoxville. And it’s just lovely. Um, she does have a website, and I will, I’ll link that. So, thank you very much.

DD: Oh, you’re welcome, and thank you.