The “back of beyond!” Writing from North Carolina, that’s what Horace Kephart called the Tennessee side of the Great Smokies. It was nearly impossible to get there in his day and a stingy place to scratch out a living. Kephart wrote about that dark side of the Smokies in his book Our Southern Highlanders.

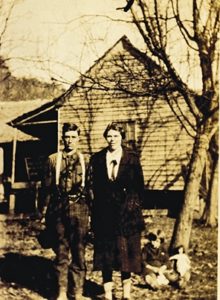

Originally known as Bear Skins Creek, Baskins Creek empties into the Little Pigeon River in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, in the heart of the town near Pi Beta Phi Elementary School. If you start there and follow the flow upstream out of the city limits into the national park through the rhododendron thickets and dog hobble and keep walking until the lay of the land gets much too steep to farm, you will find yourself on the former homestead of Homer and Pearl Ogle Bales. It is there, on the north shadowy slope of Mt. LeConte they started their married life on October 5, 1918. They were both poor bringing nothing to the union except each other, their clothes and some tools. Homer was 19-years-old, Pearl only fifteen.

Life was hard, money less than scarce. They grew their own food or hunter-gathered it: deer, raccoon, ‘possum, squirrel, fish, poke greens, watercress, blackberries, chestnuts, whatever. They farmed, grew apples and birthed their children there with the help of a midwife, as was the custom of the day. No doctor, no nurse, no running water, just the creek. Their heat came from the fireplace but it was so cold inside in winter, water in a pail would freeze.

When her own mother Nancy Elizabeth died in childbirth on December 18, 1919. Now 16-years-old, Pearl helped raise her seven younger brothers and sisters.

Homer took a job with the lumbermen in the Elkmont watershed to bring some needed money into the family. He was away Monday through Friday, returning home late, walking over Sugarland Mountain and through Cherokee Orchard to spend the weekend with his family and work the farm.

Pi Beta Phi comes to Gatlinburg

The Settlement School was founded in Gatlinburg on February 20, 1912 by the women of Pi Beta Phi fraternity looking for a poor mountain village to help. Gatlinburg had the worst muddy roads in and out of any Appalachian town they visited. After heavy rains the road from Sevierville was impassable. The tiny town was cut off from the world. Few even knew it existed. The dirt road settlement on the river was isolated and Pearl and Homer lived two miles upstream from that isolation.

The mountaineers were so cut off, it was hard for men to find work and make money; impossible for women. The ladies of Pi Phi approached Pearl. They wanted to help the women and somehow keep alive the tradition of mountain crafts. Pearl was told that if she bought a $10 loom, they would buy her woven goods to sell. If she worked hard, she might bring in $10 a week.

Homer was against the idea, thinking it was foolish. But Pearl saw the opportunity. When Homer left for the week, she took their wagon to town and bought the loom, paying it off with her piece goods before Homer’s workweek ended.

Being dutiful, Pearl gave Homer the money she earned but when he balked at giving any back, she put her foot down.

“From now on,” said Pearl, “you keep your money and I’ll keep mine.” And it was that way the rest of their 70-year married life. They became a mountaineer oddity, a two-income family bringing in roughly $15 a week, each keeping their own cash. They were separate and independent financial entities.

Homer’s money always disappeared into the bottom of his pocket never to be seen again. Pearl also saved, but she was different, she liked to buy fun things to bring entertainment to their family life. One of her first purchases was a Kodak Brownie II. Eastman’s small box camera became enormously popular, sold millions of units and could be purchased for two dollars. It also brought the word “snapshot” into our lexicon and Pearl began to document their mountaineer life. When Homer brought home possums for supper—Pearl took a photo of him. If he cut down a tree, she took another photo, and a family funeral, another photo. She actively documented their lives with small black and white images.

Their firstborn came on March 26, 1921, a daughter they named Edith. Pearl and Homer were young and life was good on the back of beyond. Yet, their isolated world was about to change.

Soon after the burial of first cousin Harrison in May 1922, Pearl became pregnant with their second child. Homer still spent the week away logging at Elkmont but in time, he added a framed extra bedroom to their Baskins Creek cabin anticipating the needs of the growing family. Pearl kept busy at the loom for Pi Beta Phi.

Their second child Maferd died the day he was born, November 22, 1923. The stillborn son is buried at the Bales Cemetery not far from Harrison’s grave on the Roaring Fork Motor Nature Trail. Maferd’s graveside service was photographed with the Brownie II, as was his small white coffin.

Pearl’s growing craft business became more lucrative allowing Homer to leave his job logging to just tend the farm. Pearl was freed to focus on her weaving. They became another mountaineer oddity: Pearl was now the sole bread-winner earning the money to buy the things they needed at Ogle’s Store cattycorner to Pi Beta Phi in often muddy downtown Gatlinburg.

And somewhere along the line, Pearl used some more of her money to buy a hand-cranked Edison Victrola phonograph that played wax cylinders to bring music into their Baskins Creek-side home. In the 1920s, Edison’s invention sold for less than $20. Each cylinder was stored in a round cardboard box much like oatmeal, and played two to three minutes of music that established the general length of songs still heard on the radio today. Neighbors would gather around the Bales’ cabin to hear the new “store-bought” music machine. Still in their twenties, Pearl and Homer were so proud of it and its many cylinders that they took it outside to be part of a family portrait. Edith is sitting in their lap.

Sell the farm?

Homer and Pearl’s log cabin was a basic saddlebag layout, single chimney in the middle with two fireplaces that faced into the opposite rooms. An additional framed “modern” bedroom ell was added as the family grew. Son Rubin was born on March 18, 1927 and Russell, my father, on December 4, 1928.

Homer and Pearl sold their property in May 1929 to become part of the new national park. They packed everything they owned and galumphed away from the hardship down the rutted wagon road to Gatlinburg. The inventory of the sale lists 127.8 acres: 40 cultivated and cleared, 87.8 timbered, 150 apple trees, unimproved road and wire fence, house with three rooms, six-pen barn, springhouse, and corn crib. The asking price was $2500. They were paid $2,250.

Once asked “Were you bitter about having to sell your property?” Grandma Pearl laughed; she always laughed, she enjoyed life. “Goodness no!” She replied. “We never thought we’d have $2,000 in our entire life.” In the parlance of today, they “took the money and run,” moving downstream to town.

Grandma Pearl, or as in the custom of the region, “Mamaw” Pearl had become loyal to the women of Pi Beta Phi, so she and Homer bought a parcel of open land between Bishop and Newton Lanes near Arrowmont and the school located at the confluence of Baskins Creek and the Little Pigeon River. They built a large two-story white house with multiple rooms, electricity and indoor plumbing, and Pearl began renting the empty rooms to working women. One of them was my mother, Mary Helen Latham, who had moved there from Panther Creek off Chapman Highway to the growing resort town to find a job.

After World War II ended, Gatlinburg became a boomtown with young GIs wanting to go on vacation with their families. In the late 1940s, Pearl opened Bales Café downtown on the Parkway specializing in “home cooked meals in the mountain fashion with hot biscuits and mountain honey.” And in the late 1950s, she opened the five-unit Bales Motel becoming one of the first businesswomen of the growing resort town. Long before the term “empowered woman” entered the vocabulary of our everyday speech, Pearl was empowered. Following her lead, Homer built himself the eleven cottage Bales Cabins on the narrow banks of the same Baskins Creek. And, yes, their monies remained separate.

In the early 1960s, Pearl retired from the long hours of the restaurant business to focus solely on her small motel, but she needed a staff. That’s when she hired me, her ten-year-old grandson, to help during the summer months. At two dollars a day, I helped her make the beds, vacuum the carpets, empty the trash, mow the lawn, and rent the rooms every summer until I went away to college.

Today, all that is left to mark where this story began at the head of Baskins is a pile of cobblestones, the stoic remains of their chimney: a gray ghost. Like most of the homes that were located within the national park’s boundaries, the home site was left to wither away, dust to dust.

The ruins of the log home are located off trail, very off trail, at the fountainhead of Baskins Creek inside the national park. There is no longer a trodden path in, you just have to know where to go. I do, but few others know the way. That’s why I offer it here as a remembrance.

Memories fade, but not of Pearl. You could call her a force of nature but that almost seems too demonstrative, but she was most definitely an empowered woman, a fun-loving, hard-working mountain girl who took advantage of every opportunity. Like her handmade patchwork quilts, she pieced together a new life for her and Homer, complete in the 1960s with a motel swimming pool where she could take her daily dip.

And yes, nary once after their purses separated were they ever mixed again, because she liked having money of her own. © Stephen Lyn Bales

Stephen Lyn Bales is from Gatlinburg and is the grandson of Pearl and Homer Bales. He is a natural historian, speaker, and author of three natural history books: Natural Histories, Ghost Birds, and Ephemeral by Nature, all published by the University of Tennessee Press. Follow his blog and on Facebook and Instagram.

Click on the book covers below to discover where to purchase books by author Stephen Lyn Bales.