Mountains are in my blood. I spent my early childhood in the Appalachian Mountains of Western Pennsylvania while my extended family was (and still is) out West. My people hail from the mountainous region of Northwestern Oregon’s Willamette Valley, down the Pacific Coast Range all the way to San Diego. Our family spent many happy summers driving through the mountains of the Oregon coast, fishing and hiking at a stunning crater lake called East Lake; exploring the Sequoia & King’s Mountain National Park; and discovering wildlife in the hills above San Diego at the Wild Animal Park (now called the San Diego Zoo Safari Park).

We moved to Kansas when I was nine so it’s not surprising, I suppose, that I had no intention of staying in the “flatland.” (For the record, eastern Kansas isn’t really flat. A fact of which my high school cross country teammates will testify.) I kept this attitude throughout my youth, and soon realized college was my way out. (I’m ashamed to say I never really considered the fact that I would be leaving family and close friends behind.) I had two primary conditions for college: 1.) It could not be in Kansas, and 2.) It had to be in or near Mountains (it didn’t matter exactly where the mountain range was located).

I considered many colleges across the country, on both coasts and in between, and there were many fine schools that fit my criteria. Then one day in late summer, 1987, the local Presbyterian minister and family friend, Rev. Peter Vial, suggested I visit his alma mater, Maryville College (MC). Peter was on the MC alumni board. He was taking a classmate of mine from his church on a college weekend visit and suggested I should come along. Maryville College, he explained, was a small school “nestled in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains.” That weekend, quite literally, changed my life.

We arrived on Thursday evening and I was introduced to my weekend roommate and host, David Yocom. David was a music major, which I aspired to become, and would become a dear friend for life. I toured the campus, sat in on a few classes and a choir rehearsal, ate in the cafeteria, and met many wonderful people. I was awestruck by the mountain view and the natural beauty of the 263-acre campus, 140 of which are the “College Woods,” which remain largely undeveloped, with walking trails, a natural amphitheater, streams, and a ropes course. I took it all in with wide-eyed wonder.

Back then the school had a population of about 700 students and I was welcomed by everyone as if I was already a classmate. While we were there, Rev. Vial took my classmate and I on a drive through Gatlinburg, part of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and got us dinner, where we experienced true mountain hospitality. On Saturday, David and some of his friends took me to a music festival in Knoxville called Saturday Night on the Town (affectionately known as SNOTT). The venue was the World’s Fair Park and bands played all kinds of music, stage after stage. This festival was my first experience of live blues music. I left Maryville that weekend knowing where I was destined to be. Maryville College was the only college to which I applied, and, once accepted, never looked further.

Maryville College was more to me than the beautiful mountains, friendly people, and great music. The college has a strong connection to its history, region, and founding ideals to “do good on the largest possible scale.”1)source: https://www.maryvillecollege.edu/about/inside/quick-facts/ (4/7/21) and Maryville College: The Founding Story, p. 9 https://www.scribd.com/document/491160318/Maryville-College-Founding-Story#from_embed That weekend I understood that people there were genuinely enamored with learning in all its forms, and felt their strong sense of duty to the earth and all its people. I learned a lot about MC’s unique history in the nearly twenty years I spent both at the college and subsequent years in the area. The principles of equality and inclusion, and the calling to do good in the world, were established by founder Rev. Isaac Anderson (1780-1857), and continue to be central to all that MC does. This may sound like an ad, but Maryville College has lived this ideal from its beginning and the list of “firsts” bears that to be true.

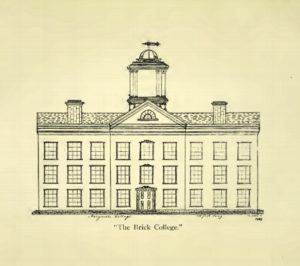

Rev. Isaac Anderson (no relation) came from Virginia, where he studied at Liberty Hall, to East Tennessee with his family in 1801; and was ordained a Presbyterian Minister the next year at twenty-two years old.2)Maryville College: The Founding Story, p 1 https://www.scribd.com/document/491160318/Maryville-College-Founding-Story#from_embed Liberty Hall later became Washington and Lee College. While studying there, one of Anderson’s classmates was John Chavis, who was one of the first African Americans to graduate from an American college, and an ordained Presbyterian minister. He was called to the field of education soon after his ordination, establishing his first school in northeastern Knox County, known as “Mr. Anderson’s Log College.”3)Maryville College: The Founding Story p. 7 In 1811, he moved to Maryville, twenty-five miles south, to become pastor of New Providence Presbyterian Church. He moved his school and students along with him. One of his students during that time was George Erskine, a former slave, freed on behalf of Anderson’s key role.4)Mr. Erskine later became a pioneer of the missionary movement in Africa. Another of Anderson’s students was one Sam Houston. Maryville College: The Founding Story p. 8 In 1819, Anderson established the Southern and Western Theological Seminary to instruct and ordain new ministers.

Rev. Anderson had a reputation as an excellent speaker and educator, and was an active leader. He was not only the president, but also the primary instructor at the seminary and an instructor at the Maryville Female Academy.5)“Women in Maryville College’s History, by Allison Franklin, The Highland Echo https://highlandecho.com/women-in-maryville-colleges-history/ At the same time, Isaac pastored two of the largest congregations in the region, located twenty miles apart: New Providence in Maryville and Second Presbyterian in Knoxville (which he organized in 1819, the same year he established his new Seminary). His schools were always open and inclusive, having Cherokee, Choctaw, and African American students, with many women attending classes as well, though they weren’t formally enrolled.

Anderson’s progressive and inclusive education practices challenged and created tensions among many local and regional leaders. William Brownlow, a pro-slavery Methodist minister who later became Governor of Tennessee,6)Brownlow was an interesting figure, actually. As an outspoken minister and journalist, he was pro-slavery but anti-secession and anti-Confederate. During the Civil War he was imprisoned for his pro-union publications, and later, as Governer, he enfranchised former slaves. once wrote that the seminary was “Dr. Anderson’s nest of Hopkinsianism and abolitionism in Maryville.”7)Helps to the Study of Pesbyterianism, published in 1834 in Knoxville. This strain, along with increasing divisions around the issue of slavery, led Anderson to broaden the school curriculum and his seminary evolved into a liberal arts school. The Southern and Western Theological Seminary became Maryville College in 1842.

Maryville College’s first decades were difficult, fraught with constant financial hardship and challenges. But through it all, the school persevered, and not only produced preachers, but also doctors, lawyers, missionaries, authors, and more. Despite Anderson’s anti-slavery views, his dedication to a balanced education showed in his faculty, which included people on both sides of the issue. When the Civil War broke out, five years after Anderson’s death in 1856, Maryville College’s four faculty members were divided and the school was closed.

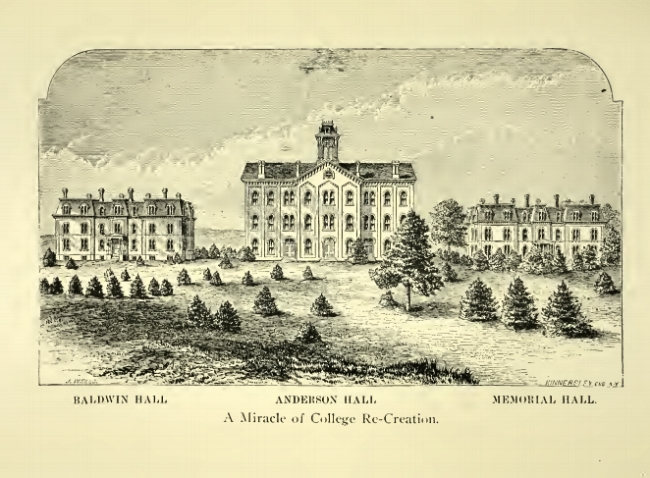

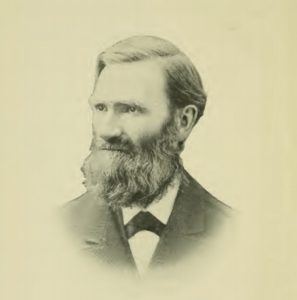

During and after the war one faculty member and former student, Thomas Jefferson Lamar, remained. He saw the buildings destroyed during the years of Confederate occupation, and, after the war was over, he was determined to bring Maryville College back. He did just that in September of 1866 with thirteen students in a ramshackle building. Lamar is rightfully considered MC’s second founder and continued the mission Isaac Anderson began. The college re-opened fully integrated, the same way it began. One year later, in 1867, women were admitted as full coed students alongside men.

That same year the Board of Directors publicly announced their position on race declaring “We deem it much to the credit of this institution that it has from its very existence stood upon a broad Christian basis excluding none from its benefits by reason of their race or color.”8)Maryville College: The Founding Story p. 12 From that point on, the students, faculty, and leadership of Maryville College has worked to fulfill Isaac Anderson’s pledge to “do good on the largest possible scale.”9)This motto can be found on the Maryville College About page, under “Mission & Vision.”

For a small school in the foothills of East Tennessee, Maryville College has seen a lot of “firsts,” and a great many of its graduates have gone on to do some amazing things around the world. I have listed a few of the highlights here for you. You can see the full timeline of MC’s surprising history here.

- Student Charles Todd wrote Woodville; or, The Anchoret Reclaimed (1832), the first novel written by a Tennessean and the first published novel in Tennessee.10)https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/literature/

- The first Bachelor’s Degree conferred on a woman in Tennessee was given to Mary Wilson in 1875. She was the older sister of future president Samuel Tyndale Wilson and an active part of the local Women’s Suffrage Movement.

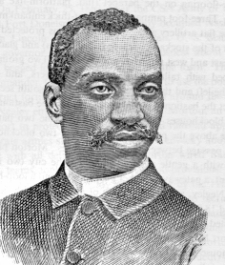

- In 1880 MC granted the first degree to an African American in Tennessee, William H. Franklin. Franklin was a successful minister and educator who established Swift Memorial College in Rogersville, Tennessee. Swift Memorial had a close relationship with MC throughout its history. You can learn more about Franklin and Swift

William H. Franklin – tnstate.edu Memorial by watching this documentary produced by Black in Appalachia.

- The only time in Maryville College’s 200+ year history that it was not an integrated institution was between 1901 and 1954, when the state’s Jim Crow law was in place establishing racial segregation. Newly appointed MC President Samuel T. Wilson opposed the law in 1901, and in 1954, as soon as it was declared unconstitutional, his successor, President Ralph W. Llyod, immediately re-integrated the classrooms. MC was among the first in the nation to do so.11)Maryville College; An Early Leader in the Struggle for Biracial Education in Tennessee, 1819-1901. By James B. Jones, Jr., Public Historian, Tennessee Historic Preservation Office, Nashville, Tennessee. This is a good article describing MCs history of integrated education.

- Nageeb Arbeely was a member of the first Syrian family to come to the US. In 1878 they settled in Maryville, where Nageeb attended MC. After graduation he went to NYU and spent his life serving as a member of the US Immigration Service helping fellow immigrants. In 1887 he was appointed by Pres. Grover Cleveland as the US Diplomat to Jerusalem.

- Kin Takahashi is an MC legend for many reasons. He was a Japanese student who transferred to Maryville in 1888. An energetic leader and athlete, he organized fellow students into launching MC’s first football team in his first year attending. (Three years before University of Tennessee, Knoxville, did so in 1891.) Leading up to his graduation in 1895, he founded a campus YMCA, and persuaded “the college administrators . . . the student body, Maryville town residents, and potential donors” that the association was needed. The building was constructed and funded entirely by students working with local craftspeople. The students made the bricks onsite themselves and named the building Bartlett Hall upon completion. It currently serves as the college’s student union.12)Maryville College “Who Was Kin Takahashi” 13)Maryville College: The Founding Story, 15-16 Sadly, Mr. Takahashi died of an illness just two years after his graduation at thirty-six years old. His legacy of hands-on service to his campus, church, and community is honored today in MC’s long-running Kin Takahashi Week, when alumni come together at MC, and beyond, to perform all kinds of community service.

- The oldest building on the historic campus is Anderson Hall, completed in 1870, and is still in active use. It re-established MC on its new campus after the end of the Civil War. Renovations to the iconic building were completed in 2015.

- Isaac Anderson’s log cabin home was restored and relocated to the Great Smoky Mountain Heritage Center, dedicated in February of 2019. “The two-story cabin where Anderson lived before founding Maryville College was slated for demolition in September 2017, when donors raised the necessary funds to move the structure to Townsend.”14)“Isaac Anderson Cabin dedicated in new home”

- All in all, at least eight campus buildings that comprise the Maryville College Historic District are listed on the National Registry, all of which are still actively used.15)source: National Register of Historic Places https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Register_of_Historic_Places_listings_in_Blount_County,_Tennessee.

**Featured Image: aerial view of Maryville College – from the MC website

References

| ↑1 | source: https://www.maryvillecollege.edu/about/inside/quick-facts/ (4/7/21) and Maryville College: The Founding Story, p. 9 https://www.scribd.com/document/491160318/Maryville-College-Founding-Story#from_embed |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Maryville College: The Founding Story, p 1 https://www.scribd.com/document/491160318/Maryville-College-Founding-Story#from_embed Liberty Hall later became Washington and Lee College. While studying there, one of Anderson’s classmates was John Chavis, who was one of the first African Americans to graduate from an American college, and an ordained Presbyterian minister. |

| ↑3 | Maryville College: The Founding Story p. 7 |

| ↑4 | Mr. Erskine later became a pioneer of the missionary movement in Africa. Another of Anderson’s students was one Sam Houston. Maryville College: The Founding Story p. 8 |

| ↑5 | “Women in Maryville College’s History, by Allison Franklin, The Highland Echo https://highlandecho.com/women-in-maryville-colleges-history/ |

| ↑6 | Brownlow was an interesting figure, actually. As an outspoken minister and journalist, he was pro-slavery but anti-secession and anti-Confederate. During the Civil War he was imprisoned for his pro-union publications, and later, as Governer, he enfranchised former slaves. |

| ↑7 | Helps to the Study of Pesbyterianism, published in 1834 in Knoxville. |

| ↑8 | Maryville College: The Founding Story p. 12 |

| ↑9 | This motto can be found on the Maryville College About page, under “Mission & Vision.” |

| ↑10 | https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/literature/ |

| ↑11 | Maryville College; An Early Leader in the Struggle for Biracial Education in Tennessee, 1819-1901. By James B. Jones, Jr., Public Historian, Tennessee Historic Preservation Office, Nashville, Tennessee. This is a good article describing MCs history of integrated education. |

| ↑12 | Maryville College “Who Was Kin Takahashi” |

| ↑13 | Maryville College: The Founding Story, 15-16 |

| ↑14 | “Isaac Anderson Cabin dedicated in new home” |

| ↑15 | source: National Register of Historic Places https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Register_of_Historic_Places_listings_in_Blount_County,_Tennessee. |

![Union Academy, [[The Log College]] from Samuel Tyndale Wilson's book A Century of Maryville College, 1819-1919, A Story of Altruism_Fotor700 cropped](https://wp-modula.b-cdn.net/spai/q_glossy,ret_img,w_700,h_406/https://www.appalachiabare.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Union-Academy-The-Log-College-from-Samuel-Tyndale-Wilsons-book-A-Century-of-Maryville-College-1819-1919-A-Story-of-Altruism_Fotor700-cropped.jpg)

Whenever I am asked, “How did Tom ever get to Tennessee for college?” I give them the same answer you gave. “Not in Kansas and mountains.” I think Peter Vial would really appreciate this article. I am happy that I have been able to participate in your Tennessee journey. What a nice tribute to your Alma Mater!

It has been quite a journey, and I couldn’t have done it without you!