Some time ago, my son and I toured the Museum of Appalachia in Clinton, Tennessee. And, let me tell you, it is a treasure trove of Appalachian everything – from the pioneer days onward. The museum is located within view of Andersonville Hwy, is surrounded by an abundance of native trees, and sits atop lush, green flatlands with scattered knolls and valleys. The main building houses gifts, “whatnots,” and souvenirs; and the attached Museum Restaurant serves light meals until 2:00 p.m. Once you begin the self-guided tour, don’t be surprised by the dozens of peacocks roaming about.

My son and I strolled the walkways, meandering with an awe-like wonder, passed several cabins, took a gander inside a historic jail, saw a smithy, gazed at farm life, discovered eras of simulated living, and sat in an old one-time church/school, etc. At one point, my eye caught a sign that read: “Mark Twain Family Cabin.” My initial thought was “This isn’t real. It must be a representation or replication.” But it is real. The Clemens’ family cabin was moved to The Museum of Appalachia, from Fentress County, Tennessee, an area where the family lived for over fifteen years before Twain’s birth in Missouri on September 30, 1835. The little cabin was brought to the museum in 1995, where it has been preserved and maintained.

As mentioned in the introduction to our category, “Appalachian Connections,” Mark Twain has a bond with Appalachia, and not simply because his family lived in the region. His mother, Jane Lampton Clemens (1803-1890) and his grandmother, Margaret Casey Lampton (1783-1818), were born in Appalachia’s Adair County, Kentucky.1)In his autobiography, Twain refers to the spelling of this surname as “Lambton” but, as he states, “with a p, for some of the American Lamptons who could not spell very well in the early times and so the name suffered at their hands.” Twain says of his mother: “She was of a sunshiny disposition” and “always had the heart of a young girl.”2)Kaplan, J. (1974). Mark Twain and His World. New York: Simon and Schuster. Retrieved from https://archive.org/ p. 14 Jane married Twain’s father, John Marshall Clemens (1798-1847), in 1823 in Lexington, Kentucky. John was born somewhere in Virginia, as was Mark Twain’s grandfather and namesake, Samuel Clemens (1770-1805). Sadly, Samuel died after a tragic construction accident.3)Kirk, C. A. (2004). Mark Twain: A Biography. Westport: Greenwood Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/, p. 6 Young John and his family eventually moved to Adair County, where he presumably met Jane. According to Twain, his father was Jane’s polar opposite. Twain describes him as a “stern, unsmiling” man who “never demonstrated affection for wife or child.”4)Kaplan, J. (1974). Mark Twain and His World. New York: Simon and Schuster. Retrieved from https://archive.org/ p. 14

Perhaps Twain described his father’s true character; or, maybe his father’s stoicism lies in a drive (and constant attempts) for success. John diligently studied and became a lawyer. Shortly after their marriage, he and Jane moved to Gainsborough, Tennessee in Jackson County, and, in 1825, their first child, a son named Orion, was born (Another source records his birth as being in Fentress County.). John’s law profession suffered in Gainsborough so the family tried their luck in Jamestown, Tennessee (Fentress County), where he was “elected as the court’s circuit clerk.”5)Kirk, C. A. (2004). Mark Twain: A Biography. Westport: Greenwood Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/, p. 7 He drafted the plans for the county’s first courthouse and jail.6)(Hogue, A. R. (1916). History of Fentress County, Tennessee: The Old Home of Mark Twain’s Ancestors. Nashville: Williams Printing Co. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_Fentress_County_Tennessee/b1wvAAAAYAAJ?q=Clemens&gbpv=1#f=false, p. 12 By all accounts, the Clemens family was considered the elites of the town. They “attended balls” and had the largest house in the area. In Jamestown, John Clemens purchased (all at one time) a sizable 75,000-100,000 acres of land, which he saw as an “investment in his family’s future,” saying: “Whatever befalls me now, my heirs are secure. I may not live to see these acres turn into silver and gold, but my children will.”7)Kirk, C. A. (2004). Mark Twain: A Biography. Westport: Greenwood Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/, p. 7Twain used this Appalachian Tennessee area as the setting for his book The Gilded Age, coauthored by Charles Dudley Warner.8)Twain, M. (1990). The Autobiography of Mark Twain. (C. Neider, Ed.) New York: Harper Perennial. Retrieved from https://archive.org/ p. 18

The Clemens’ added two more children while they lived in Jamestown: Pamela in 1827, and Margaret in 1830. Some year between these births (1828 or 1829), the couple had another son named Pleasant Hannibal Clemens who died in infancy. Pleasant is listed as buried in Fentress County but in an unknown grave. Success in Jamestown waned as community development steadily slowed, making it difficult for business. John’s law cases dwindled so he changed careers and became a merchant, but this venture also failed.

The family moved from Jamestown to the unincorporated town (still located in Fentress County) of Pall Mall, Tennessee near Wolf River.9)Kirk, C. A. (2004). Mark Twain: A Biography. Westport: Greenwood Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/, p. 7-8 John had no better success in Pall Mall. The couple’s fourth child, and the last of Twain’s siblings born in Tennessee, Benjamin Clemens, was born in 1832. John once again tried his luck as a merchant and opened a store inside a post office. He moved his family into a small log cabin he’d built himself – the very cabin that sits at the Museum of Appalachia. Their financial situation, however, continued to decline.

Jane’s brother-in-law convinced the family to move to Missouri, where he offered John a partnership in his fairly successful store. Mark Twain was born in the “Show Me State” (as Samuel Langhorne Clemens) just as Halley’s Comet streaked across the night sky. He was premature and sickly,10)Kirk, C. A. (2004). Mark Twain: A Biography. Westport: Greenwood Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/, p. 8yet, thankfully, he overcame his fragile birth and became one of our nation’s literary giants. The last of the Clemens children, Henry, was also born in Missouri on July 13, 1838. John Clemens’ luck met ups and (mostly) downs. At one point, the family was so destitute, he traveled back to Tennessee to find work but failed.11)Kirk, C. A. (2004). Mark Twain: A Biography. Westport: Greenwood Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/, p. 15

All in all, the Clemens family spent about seventeen years in Fentress County, Tennessee. The land John Clemens left as a legacy for his children was greatly mishandled (pretty much piece by piece and acre by acre) by the Clemens’ adult (male) children. Buyers and prospectors took advantage and coaxed the Clemens brothers into believing the minerals on the land would make them all rich. But that wealth never surfaced. Instead of such promise, the entire land issue brought decades of see-saw negotiations and transactions. Twain says the land “influenced our life in one way or another during more than a generation.”

Indeed, Twain’s The Gilded Age, characterizes greed and status and obsession. The main character, Squire Hawkins, is introduced to the reader in the book’s beginning. Hawkins has purchased “Tennessee Land” that will eventually make the family rich, though Hawkins believes this wealth won’t occur during his lifetime. Sound familiar? Twain writes about Jamestown under the guise “Obedstown, east Tennessee”12)Twain, M. (1990). The Autobiography of Mark Twain. (C. Neider, Ed.) New York: Harper Perennial. Retrieved from https://archive.org/ p. 1813)Twain, Mark; Charles Dudley Warner. (1915). The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. New York: Harper & Bros. Retrieved from https://archive.org/index.php, p. 1 He admits his sources for the area were “from hearsay, not from personal knowledge.” I imagine Twain was handed a cynical oral history about the area because he writes somewhat critically of the town:

You would not know that Obedstown stood on the top of a mountain, for there was nothing about the landscape to indicate it – but it did: a mountain that stretched abroad over whole counties, and rose very gradually. The district was called the “Knobs of East Tennessee,” and had a reputation like Nazareth, as far as turning out any good thing was concerned.14)Twain, Mark; Charles Dudley Warner. (1915). The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. New York: Harper & Bros. Retrieved from https://archive.org/index.php

Of Hawkins’ residence, Twain writes:

The Squire’s house was a double log cabin, in a state of decay . . . Rubbish was scattered about the grassless yard; a bench stood near the door with a tin wash-basin on it and a pail of water and a gourd . . . There was an ash-hopper by the fence, and an iron pot, for soft-soap-boiling, near it.

This dwelling constituted one-fifteenth of Obedstown; the other fourteen houses were scattered about among the tall pine trees and among the cornfields in such a way that a man might stand in the midst of the city and not know but that he was in the country if he only depended on his eyes for information.15)Twain, Mark; Charles Dudley Warner. (1915). The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. New York: Harper & Bros. Retrieved from https://archive.org/index.php, pgs. 1-2

Twain’s tone may have been due to his father’s dashed hopes and promises of success in the region. Or, it could be because the Appalachian land John purchased for his children’s inheritance never profited and was, therefore, a bitter remnant in Twain’s psyche. His younger brother, Henry, the baby of the family, died in a tragic steamboat explosion in Memphis, Tennessee. Though the place of death wasn’t in Appalachia, it was Tennessee. The death devastated Twain, partly because he supported Henry’s desire to travel the riverways like his older brother Twain did.

Whatever the reason, the Clemens family lived in Appalachia. That’s a fact. Five of their seven children were born here. That’s a fact. And yet, there’s something I believe John Clemens never considered: the gradual, mesmerizing aura that exists in this region. The perception is especially felt by newcomers and/or “outsiders”. People here are too sluggish or Life’s too slow here or There’s nothing to do here or I’m so bored I can’t stand it. The only reason I deem this little digression relevant is because John Clemens had an expectation about Fentress County, Tennessee, that never considered the slow, rhythmic lifestyle of the region. Oh, it’s not that people are intent on doing nothing or not progressing. It’s that they don’t consider these things at all. They exemplify, in a word, contentment, an elusive state for John Clemens since he was someone who itched to climb that social ladder and make a crapload of money on the way up.

So, I’m brought back to the little log cabin that sits so unassuming off a pathway. My ear bends to the sound of my shoes clopping atop the wooden porch. I peer into the small one-room area with period furniture and belongings, and imagine the little Clemens children there, somewhere playing, helping, crying, wanting. And I feel them. I am grateful, really. Even though Twain didn’t paint the region in the best light due to circumstances and oral history, he nevertheless painted it. His writings about the area really represent what I like to call the “my people” syndrome: “I can talk about my people all I want. But you can’t.” And, even if Twain never wanted to claim he was somehow connected to this region, the facts are he is. And that’s forever.

Take some time to read Twain’s short story, “Journalism in Tennessee” below. It’s hilarious. Just click on the pages.

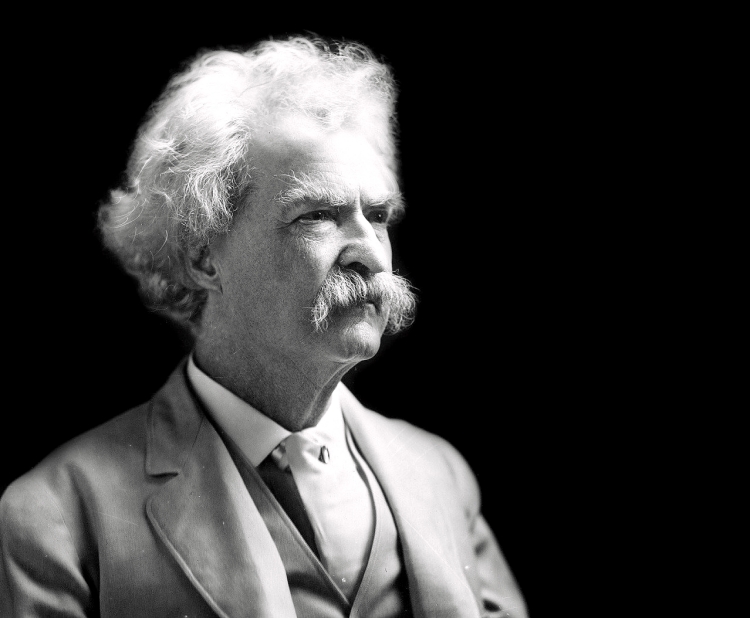

**Featured Image: Mark Twain – pixabay

References

| ↑1 | In his autobiography, Twain refers to the spelling of this surname as “Lambton” but, as he states, “with a p, for some of the American Lamptons who could not spell very well in the early times and so the name suffered at their hands.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑4 | Kaplan, J. (1974). Mark Twain and His World. New York: Simon and Schuster. Retrieved from https://archive.org/ p. 14 |

| ↑3 | Kirk, C. A. (2004). Mark Twain: A Biography. Westport: Greenwood Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/, p. 6 |

| ↑5, ↑7 | Kirk, C. A. (2004). Mark Twain: A Biography. Westport: Greenwood Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/, p. 7 |

| ↑6 | (Hogue, A. R. (1916). History of Fentress County, Tennessee: The Old Home of Mark Twain’s Ancestors. Nashville: Williams Printing Co. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_Fentress_County_Tennessee/b1wvAAAAYAAJ?q=Clemens&gbpv=1#f=false, p. 12 |

| ↑8, ↑12 | Twain, M. (1990). The Autobiography of Mark Twain. (C. Neider, Ed.) New York: Harper Perennial. Retrieved from https://archive.org/ p. 18 |

| ↑9 | Kirk, C. A. (2004). Mark Twain: A Biography. Westport: Greenwood Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/, p. 7-8 |

| ↑10 | Kirk, C. A. (2004). Mark Twain: A Biography. Westport: Greenwood Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/, p. 8 |

| ↑11 | Kirk, C. A. (2004). Mark Twain: A Biography. Westport: Greenwood Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/, p. 15 |

| ↑13 | Twain, Mark; Charles Dudley Warner. (1915). The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. New York: Harper & Bros. Retrieved from https://archive.org/index.php, p. 1 |

| ↑14 | Twain, Mark; Charles Dudley Warner. (1915). The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. New York: Harper & Bros. Retrieved from https://archive.org/index.php |

| ↑15 | Twain, Mark; Charles Dudley Warner. (1915). The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. New York: Harper & Bros. Retrieved from https://archive.org/index.php, pgs. 1-2 |

![Mark Twain at 15 [[holding a printer's composing stick with letters SAM]] - wikimedia_Fotor625 cropped scenes auto](https://wp-modula.b-cdn.net/spai/q_glossy,ret_img,w_625,h_821/https://www.appalachiabare.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Mark-Twain-at-15-holding-a-printers-composing-stick-with-letters-SAM-wikimedia_Fotor625-cropped-scenes-auto.jpg)

I enjoyed learning about Twain’s Tennessee connection in this interesting and well-researched piece.There is a saying attributed to multiple sources, from the Talmud to Steven Covey, that might explain John Clemens’ view of Fentress County: “We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.” The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer fueled many imaginary adventures in my Tennessee childhood. One of my favorite Twain essays, far afield from Tennessee, is “The Awful German Language.” I discovered it while I was in Bitburg, Germany struggling to learn the language and torturing the local populace with my twangy and mangled “Tennessee Deutsch.” Twain’s hilarious send up of the language mirrored my own painful experience. As to the Museum of Appalachia, thank you for adding another place to visit to my bucket list.

I’m glad you enjoyed the post. I was never a big fan of Twain until I was well into adulthood. I picked up “Roughing It” when a difficult time begged for anything to put a smile on my face. And I wasn’t disappointed. I laughed and chuckled all the way. I will definitely read “The Awful German Language” and look forward to his satire as it drips from the pages. I do hope you can visit the museum. It’s incredible and quite dizzying.