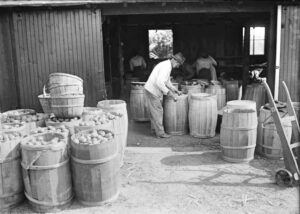

Apple groves covered the mountain sides rolling down from Fancy Gap, around Cana and Galax, and down the mountain to Mt. Airy. Huge fruit warehouses dotted several surrounding counties, rambling, weathered old structures with wide cracks between their rain-swollen and sun-dried rough-cut lumber siding. The old folks loved to sit on the wide porches of the storehouses and listen to rain drum on their rusted tin roofs as they separated and graded the ripe fruit and talked about olden times.

Lottie remained in camp that first day, moody and restless, wanting to do something but not knowing what. She was not accustomed to sitting still, but that day she spent a lot of time sitting on the creek bed listening to the murmur of the water and wondering if anyone in Iron Forge would remember who she was.

The few men who had trooped off that morning began returning in the early afternoon. Not all of them were prepared to put in the necessary hours for a dollar bill. Some returned with a stagger in their steps; all were dusty and weary. One-tooth Bill, as the wizened old man of the camp was called, already had a mulligan stew bubbling and coffee boiling.

Next morning Lottie joined the men kicking up dust on New Cut Road, stiff from a night on the ground and stretching their shoulder and back muscles. With her battered fedora pulled low over her face, Lottie looked at a distance like any other young hobo clomping along in work boots and overalls.

Lottie’s knot of men chose a pickup going south toward Cana. She and another picker were dropped off at the old Foley farm, a small home operation owned by a widow, a soft-spoken woman of maybe sixty years. Lottie quickly earned the widow’s respect for her focused and energetic work in the trees. Some evenings Lottie would stay behind after the other pickers jumped on the trucks to return to the hobo camp.

The two women were out by an old stone well that had been outfitted with a cast iron hand pump before Mr. Foley passed. The water was cold year-round and had a hint of sweetness to it. The Widow Foley was using it to wash Lottie’s red, tangled locks. She had twisted the hair into a rope and squeezed out the water, then wrapped a towel around her head to look like a turban. Lottie’s shirtfront was soaked.

They sat on the edge of the well, the stone blocks cold to their butts, Ma Foley in a faded, shapeless print dress and smoking her worn corncob pipe. The old woman rubbed the backs of her swollen hands to soothe what the locals called rhumatiz. Her skin was dry and thin as paper and blue veins shone through. They watched as her fat chickens clucked and pecked and scolded around the pump on their way to the coop for the night. She absently reached up to move an errant piece of gray hair back into its place. Her hair was brittle as cured straw.

“Honey, you got the richest hair I ever seen!” she said. “You know this here mane is gonna drive men mad, don’t ya? That and them dugs of yourn. You better equipped than some growed women I know. You know that, doncha?” Lottie blushed.

The old lady chuckled and her shoulders did a little dance. She ran the back of her hand across her nose out of habit.

Lottie’s work clothes bubbled nearby in a cast iron pot where Ma Foley boiled her weekly wash. At other times, the pot cooked stews and boiled hog meat.

Lottie was drawn to this resilient woman, to her warm and slow ways of doing things and her way of talking to her like she was kin. Ma Foley didn’t judge her about her dress or her behavior, and Lottie was trying to figure out what it meant to be grown, how to act like an adult. It felt like she had gone into the Staunton asylum as a child and came out as something else, but she didn’t know what the something else was.

Lottie was spending more time helping Foley with farm chores than she was picking apples: chopping wood and milking the old cow, manuring the garden, putting up vegetables and stringing beans and peppers. She was spending more nights there, sleeping in the missing daughter’s bed, wearing the overalls and flannel shirts of the missing son, even after Ma Foley offered her the daughter’s dresses.

“Honey, you look mannish in them men’s britches and that hat looks like a mule sat on it. You orta throw that nasty thing away!”

“I cain’t work in them things!” was Lottie’s response to the offer of women’s wear.

The two women hung Lottie’s clothes on a wire strung between two pecan trees. They locked up the chickens in the hen house and Ma Foley showed Lottie her little homemade still. It had become their routine to have a taste of homebrew after work was done.

“Almanac says we gonna have a mild winter,” Miz Foley would remark apropos of absolutely nothing. As with all farm people, the weather was a constant in her life, requiring a little preemptive praying and at times some conjuring. She never killed a black snake that she didn’t leave it stretched across the road or draped on a fence post. Helped bring the rain.

Whenever the pair had barn chores or were having their little afternoon toddy, Lottie would remark on the dusty old Ford pickup that sat in the middle of the barn floor, grungy and tired-looking, like a turn-of-the-century relic waiting for a museum. She would sit in the driver’s seat with both hands on the big wooden steering wheel and pretend to drive. The widow would watch the girl and her far-off look, gazing out the barn door like she had found paradise and was driving toward a rising sun.

“Maybe we could take the old Lizzie out Saturday,” said Ma Foley after they were settled on the porch watching the slow fall of an autumn sun. “It’s Farm Day over to Galax, and we could take some pecans and greens to sell.” She watched as Lottie’s eyes brightened. “We need to get offen this farm now and agin.”

“I got some extra fatback cured from last year. We could scare up some gourds, take some of my stored-up taters, maybe some sassafras and honey. We might make a day of it. I ain’t been to the city in months. Maybe I’ll even teach you how to drive that old wreck this week. Hurts my shoulders when I drive it.”

Two days later after chores were done, Ma Foley climbed into the old pickup truck and instructed Lottie to turn the crank.

“Watch out that crank handle don’t come back on ya. It’s bad for that. Broke more than one arm that I know about.”

Lottie turned the crank and the old machine caught spark, coughed, belched a cloud of black smoke and rattled to life. Ma Foley grinned and told her to “jump in.”

They tootled around the yard as Ma Foley demonstrated the pedals and levers.

“Now, see here, this lever by the wheel gives you speed. It’s the throttle.”

She stopped in the yard and used a floor lever by her left shoulder to shift the engine into neutral and then into low gear.

The vehicle moved slowly forward as Ma Foley pressed the left pedal and explained every move to Lottie who watched intently.

“Don’t use that middle pedal, that’s reverse.” She chuckled. “And this right one here is yore brake,” and she demonstrated by bringing the car to a stop.

“Now, you git under the wheel,” she said to Lottie.

“Aw, I don’t believe I can do all that,” Lottie protested.

“No, come on now, that’s the onliest way you’ll ever learn. Now, git over here and drive this thing. If I can do it, you can do it.” And she pushed the lever to neutral as the little engine clattered and the old truck rocked gently side to side.

Lottie pushed the floor lever into low gear and gently moved the throttle, and the truck slowly moved off. She spent some time wrestling with the big steering wheel and brought the truck to a slow stop. The engine raced, Lottie squealed, and Ma Foley reached over to reduce the throttle.

“It’s okay, you jist got to git the hang of it. You’ll do alright. Let’s go agin.”

The little truck looked like an ornery mule rearing and kicking in the yard. It took a lot of stalling and bucking and racing before Lottie finally made some sense about the vehicle. She took it out onto the rutted road that ran past Foley’s farm and let the truck run straight on for several minutes. She wrestled it into a turn without stalling and drove back to the farm. Her face brightened when she pulled the machine into the yard no worse for wear.

Widow Foley patted her shoulder and praised her skills on handling the vehicle. Tomorrow they would load the truck and drive to Galax for Farm Day.

They sat in the swing on the wide porch that evening snapping beans and shelling peas and stringing red peppers to dry. They listened to the sounds of the dying day and talked in low voices about the garden, the flivver, the color of the autumn leaves. Ma Foley hummed an off-key tune.

“I remember setting with my aunts and shelling beans,” Lottie said. “It was really nice, with the neighbors pitching in, drinking sweet tea, ever’body telling stories and like that. I liked the stories, ‘specially the ghost ones.”

“What happened to ‘em, Honey?”

“I don’t know. I ain’t seen ‘em in a long time. I went to live with my daddy . . . and then I went up to Staunton for a spell. It’s been a long time.”

Lottie went quiet and Ma Foley let the quiet lie. After several minutes she said, “You know you can stay here as long as you want. I like having you around.”

Lottie stared into the porcelain pan and concentrated on shelling her beans.

“I’ve got to get back to Iron Forge,” she said.

**

Galax on Farm Days was a carnival. The cotton mills and furniture factories closed at noon to allow their employees to join the goings-on. Men, women and children walked about with cotton lint in their hair. A girl of ten or twelve walked alone, her hair as white as house paint. Men from the furniture factory reached for apples with hands dark as mahogany from the wood stain they worked with, their overalls stiff as boards from the varnish and thinners that splashed them all day. Farmers sat with wagon loads of burley tobacco leavings from the fields which made easy rolling for cigars and for chewing, even if some of it was green.

Music rang from every corner of town as fiddlers competed for the fastest tempo, and scattered groups picked banjo and guitar while squatted behind the rows of farm trucks and wagons that lined up along Railroad Avenue.

A peanut grinder with a monkey on a leash wearing a tiny red hat made his own squeaky music and sold peanuts for a penny a handful. The monkey was wide-eyed and made squeaky noises as he jerked pennies from the hands of children to give to his master while the grinder churned away at his music box.

Lottie nudged her way through the mangle of people and vehicles and found a slot to park their loaded pickup, nervous to be driving through such a crowd. She lighted from the truck and pulled away the slats that held their produce inside.

“You go on,” Ma Foley urged her. “Go enjoy yourself and come on back to spell me in a few minutes.”

Lottie fussed around with the bins and baskets of vegetables, setting them in rows so they looked more cared for. She then wandered about the train station and walked a couple of blocks into town, peering through the store windows at clothes and furniture and canned foods. She never cared for fancy clothes, but she liked to window shop in the clothing stores and browse in the hardware stores, lifting a pistol or a rifle to feel its heft.

She became bored with the sidewalk crowds and returned to Railroad Avenue and its rows of wagons and trucks just in time to see a burly furniture worker sneak an onion from Ma Foley’s truck bed while the woman was busy talking to another buyer.

Lottie grabbed the man by his overall strap.

“Put that back where you got it, you thief! Put it back!”

The worker pushed hard against Lottie’s chest, but she clung to his strap like tar on a road. He struggled to pull away, dragging Lottie with him as he tried to run.

“You piece of dung! Give me that onion! Help! Police! Help!”

Ma Foley turned toward Lottie’s screams, then ran to her aid.

“Lottie, let him go! Let him go!”

Several of the farmers left their trucks and wagons and edged toward the thief who punched Lottie in the face and threw the onion at Ma Foley.

Lottie’s grip slipped and she fell to the road, cursing at the thief’s retreating back and bleeding from her nose from the punch.

She drew lots of sympathy from the farmers and their wives, the women dusting her trousers and cooing, the men paying her a simple nod and a “preciate it.” The men admired Lottie’s spunk but were uncomfortable with her brashness. They didn’t approve of women fighting, even when they were in the right.

“Honey, you got to get that temper of yore’s under control. You cain’t fix ever thing that’s wrong in the world.”

“But he stole from us! He stole from us!”

“Honey, it was only an onion. I’d-a give it to him iffen he’d asked.”

“Yeah, but he didn’t ask. He just took it.”

“Honey, you ever took something that weren’t yorn? It was only an onion.”

Lottie searched the ground for an answer, scuffed her toe through the dust, and walked away from Ma Foley toward the truck.

They were quiet on the return trip to Cana, each nursing her own thoughts. By the time they had parked the truck and unloaded the produce that didn’t sell, they were talking again, and they passed the evening on the porch listening to night sounds. Ma Foley broke out a pint jar of her home whiskey. “Made it myself,” she said to Lottie. Next morning, Lottie’s bed was made but she was nowhere to be found.

I have lived and worked in the best of two worlds: the Outer Banks of North Carolina and the Blue Ridge Mountains of southwest Virginia. I draw inspiration from both sources. I formerly worked as a researcher/ writer for the Division of Archives & History (N.C.) and as Director of the North Carolina Maritime Museum.

Click on the images to find out more about Rod Barfield’s books:

**Featured image: Picking Apples – G.P. Negative 53A, G. Brooks, Wikimedia, Picryl, Public Domain