Emmett Machinists of Knoxville vs. the Quicksteps of Spring Hill

Though the Saturday afternoon in August was hot and sunny at the Historic Ramsey House in Knoxville, Tennessee,1)The Ramsey House was built in 1797 for Col. Francis A. Ramsey, the patriarch of one of Knoxville’s early prominent families. the weather was really quite pleasant in the shade. A fitful breeze whispered free and easy, and storm clouds gathered somewhere off to the north. It was a great day for a baseball game, and a small, enthusiastic crowd, my son Tré and I included, had gathered around the large field behind the Ramsey House for that very reason. Baseball is a family tradition dear to my heart, and one I thoroughly enjoy passing on. You might ask yourself, why play baseball at the Ramsey House? Well, this was not your average baseball game. This was a game of base ball (two words) played by members of the Tennessee Association of Vintage Base Ball (TAVBB).

Ramsey House Executive Director, Kelley Weatherly-Sinclair, and a few of her staff members, sold hot dogs, chips and cold beverages. (I mean, you can’t have a ballgame without a hot dog, can you?) They were readily on hand to give tours of the historic property. They were very friendly and a joy to talk to while we all watched the game. Ramsey House has hosted these games for over six years now.

Tré and I sat and surveyed the grounds. The ball field was framed by wooden benches under the players’ canvas tents, situated on either side of a backstop. A large chalk score board was set up near third base. There were no bleachers, although a few modern shade tents were set up for general use, and spectators brought their own folding chairs. The surroundings were what you’d expect in East Tennessee’s full growth of high summer – a field surrounded by lush, green woods, tall, swaying grasses, and thick underbrush. Nature provided the outfield’s only boundary from a cleared field that gave way to the thicket. A stream trickled beyond this area, feeding the nearby French Broad River. We all settled in, waiting with anticipation for the game to begin.

The TAVBB began in 2013 with two teams. By 2019, the league expanded to twelve teams across Middle and East Tennessee, with four teams in the Appalachian Mountains of East Tennessee.2)Knoxville Holstons, Emmett Machinists, Lightfoot Club of Chattanooga, and Mountain City Club of Chattanooga They are part of the national Vintage Base Ball Association, a loose organization which boasts over 400 clubs across the country. The clubs and regional associations are like many such groups, essentially local with varying degrees of formal organization, not unlike the post-Civil War teams they recreate.

The Tennessee Association was founded with a passion for history and an educational mission, so it is no surprise that members include college professors, doctors, and school teachers bound together by the love of history and base ball. One key departure from the period they simulate is the absence of restrictions for who can join and play. The only requirement is interest and participation. They welcome everyone, regardless of gender, race, religion, or anything else. Most, if not all, teams in the Tennessee Association have female members.

As described to me, for most clubs in the Tennessee Association, history is first, base ball second. Not that they aren’t competitive; they definitely are, but they take the educational aspect of what they do seriously. The TAVBB has a more formal organization than most associations across the U.S., with a Board of Directors that includes representatives from each team. A regular season schedule culminates in an annual state championship bracket and ends with a banquet celebrating the state champs and best player(s). They participate in a number of educational events, from speaking to classes to playing games for larger events. Like all things, the ongoing pandemic put the brakes on much of that; but it’s something they look forward to revisiting.

For the most part, the vintage teams are based on groups organized in the second half of the 19th century. The Knoxville Holstons was an active team in the late 1860s and they based their uniform and colors on a Nashville newspaper article from 1868. Knoxville’s other TAVBB team, The Emmett Machinists, derives from an old Morristown team originally made up of railroad men. This “blue collar” team was an anomaly of the time and indicated a major development in the history of Base Ball. Prior to the Civil War, the game was centered primarily in the Northeastern states around gentleman’s clubs and played by the “professional” class, though it was by no means exclusive to that group. The middle class of the era had enough free time and wherewithal to travel and spend a day or two playing a game. During the war, Union soldiers brought the game with them and shared it with anyone who wanted to play – Union, civilian, or Confederate. Many Southern prisoners of war learned the game and played against the Northern soldiers stationed at the camps. Those soldiers brought it home with them after the war and formed clubs and leagues in their own communities. The post-war influx of Northerners to the South also served to rapidly spread the game.

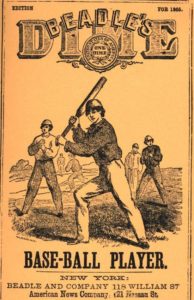

The TAVBB uses the 1864 edition of Beadle’s Dime Base-Ball Player as a foundation. The games are familiar, yet different in many key ways. The field of play has changed very little. The baseball diamond is situated as usual and the bases are ninety feet apart. Home “plate” is patterned after the original twelve-inch round disc resembling a dinner plate, unlike today’s modern house shape. The backstop is constructed of black painted wood and chicken-wire fencing with a ship’s bell mounted to one side. (This bell is rung by a player who crosses home, indicating a scored run.) The defensive positions are the same as today: pitcher, catcher, four infielders, and three outfielders, arranged in the usual way.

The TAVBB uses the 1864 edition of Beadle’s Dime Base-Ball Player as a foundation. The games are familiar, yet different in many key ways. The field of play has changed very little. The baseball diamond is situated as usual and the bases are ninety feet apart. Home “plate” is patterned after the original twelve-inch round disc resembling a dinner plate, unlike today’s modern house shape. The backstop is constructed of black painted wood and chicken-wire fencing with a ship’s bell mounted to one side. (This bell is rung by a player who crosses home, indicating a scored run.) The defensive positions are the same as today: pitcher, catcher, four infielders, and three outfielders, arranged in the usual way.

The most visible differences are noticed in equipment and uniforms. Long pants and long sleeves are worn, regardless of the temperature. Some teams wear suspenders and others wear overalls. No numbers or names are present, though some teams have letters or a team insignia on the front, and they wear hats of all kinds. (One must wear a hat to play. A forgotten hat means a player is penalized. Usually, the spectators are asked to mete out the punishment, to the amusement of all.) Of course, everything is coordinated in the team colors, and that hasn’t changed. Another difference is what is not seen: gloves. Baseball gloves weren’t common until the 1880s, so prior games were played barehanded. The ball, sometimes called an “onion,” was somewhat larger, more loosely wrapped, and the stitching was in a cross-pattern. The bats were similar to modern, wooden bats. Some were colorfully painted, some were black, and others were the usual stained wood. The bat’s only size restriction was a 2.5-inch diameter, so they varied in length, unlike today’s bats.

Each of the players has a nickname, such as Grasshopper, Fiddlesticks, Grizzly, Colonel, and Masher. To begin, players line up on either side of the umpire who stands at the center of the diamond, introduces the teams and players, and says a few words to the gathered spectators. In the 1860s, there was no “home” team. They tossed a bat to determine which team batted last, much like the coin-toss in football. 3)This is not to be confused with the modern bat toss, when a player hits a home run. Each team has a player who meets the umpire in the center. The umpire tosses the bat in the air, one player catches it and then they alternate, hand over hand, until one player grabs the knob. The winning team chooses to start on offense or defense. Once order of play is determined, one team takes the field and the umpire calls: “Striker to the line!”

Like the equipment, the game action is also familiar, but with key differences, the most obvious being barehanded play. Under the 1864 rules, a striker (batter) was out when a batted ball was caught “on the bound,” meaning on a single bounce (It could still be caught in the air, of course.). A striker could not overrun first base. If a runner came off the base and was tagged, he was out. While stealing bases was allowed, only a one-stride lead-off was permitted and base runners did not slide. The complete game rules can be found on their Rules and Customs page, and many of the main game departures can be found on their F.A.Q.

Pitching was done underhanded so there was no mound, and no balls or strikes were called.4)http://tennesseevintagebaseball.com/f-a-q/ The pitcher’s job was to put the ball in play; balls and strikes were added later to increase the pace of play. 5)I find this a bit interesting because, in today’s game, the best pitchers keep the ball out of play. For this fan at least, that creates a slower, less exciting game. As Hall of Fame broadcaster Denny Mathews has described it, it’s like watching two guys play catch. Not exactly thrilling. The pacing and flow of the old-style of play is, for me as a spectator, often more fun to watch. The fielding was also very different and more challenging. The advantage that today’s leather glove with a large woven basket provides a fielder – on both grounders and fly balls – is easy to take for granted. In keeping with the past, the ball fields are not pristine, professionally groomed fields exclusively used for baseball and they aren’t perfectly level. Playing a hard-hit grounder under those conditions is far from easy, especially barehanded.

Tré and I settled in as the game began. The day’s matchup was between the third-place Quicksteps of Spring Hill, who traveled east to the foothills of the Smoky Mountains to take on the Emmett Machinists of Knoxville, Tennessee. The Machinists wore black pants and white shirts with a red “E” over the left breast, and black caps with a wide white band. The Quicksteps wore black pants with red suspenders, plain white shirts, and red caps with thin white piping. The game was very active, with the Machinists cranking up to an early 5 – 0 lead in the top of the second. The Quicksteps answered with one run in the bottom of that inning. They shut down the Machinists in the top of the third and tacked on six more to take the lead 7 – 5. The Machinists closed the gap with one in the top of the fourth, but the Quicksteps kept pace with an answering run in the bottom of that inning to stay ahead 8 – 6. The Machinists tightened the screws on the defense and slowed the Quicksteps’ roll, keeping them off the plate and the scoreboard, if not off the bases entirely. All the while, they ground away at the lead one run at a time, to tie the game eight-all in the eighth. The Quicksteps would not be denied, though, and quick-marched their way to the bell three more times in the bottom of the eighth to climb 11 – 8. The Machinists could not overtake the lead. All-in-all a spirited contest by both teams. The game ball was awarded to the Quicksteps’ youngest player, Fiddlesticks, who played catcher and made three outs on tipped balls. Two of those tipped-ball outs came in a row to end an inning. He also struck a single, as he helped march his team to victory.

The vintage season runs from early May through September. My son and I love watching the games. On this day, our afternoon at Ramsey House is full of fun base ball, with exciting plays, good company, and new friends. The winning Quicksteps of Spring Hill doff their caps as we give three huzzas for a well-played contest. The storm front approaches, the wind picks up, and dark clouds loom closer. The equipment is stored, tents are pulled down, and chairs are packed up, all while the players enthusiastically relive the game and talk about the next one. Calls of “Well played!” and “Good game!” are heard all over the field. Satisfied, Tré and I stroll the lovely grounds of Ramsey House, talk about the game, and wonder when we can come back for another afternoon at the ball park.

I want to give a very special thank you to Klent “Biscuit” Pope and William “Doc” Hardy, who took the time to talk history and base ball with me. They were both a font of information about the history of the era, the game, and the development of the TAVBB. We had conversations not interviews, per se, so I haven’t quoted them here, but perhaps there will be a follow-up article one day. Who knows? I look forward to seeing them and all the ballists at the next game.

**All images photographed by Tom Anderson

References

| ↑1 | The Ramsey House was built in 1797 for Col. Francis A. Ramsey, the patriarch of one of Knoxville’s early prominent families. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Knoxville Holstons, Emmett Machinists, Lightfoot Club of Chattanooga, and Mountain City Club of Chattanooga |

| ↑3 | This is not to be confused with the modern bat toss, when a player hits a home run. Each team has a player who meets the umpire in the center. The umpire tosses the bat in the air, one player catches it and then they alternate, hand over hand, until one player grabs the knob. The winning team chooses to start on offense or defense. |

| ↑4 | http://tennesseevintagebaseball.com/f-a-q/ |

| ↑5 | I find this a bit interesting because, in today’s game, the best pitchers keep the ball out of play. For this fan at least, that creates a slower, less exciting game. As Hall of Fame broadcaster Denny Mathews has described it, it’s like watching two guys play catch. Not exactly thrilling. The pacing and flow of the old-style of play is, for me as a spectator, often more fun to watch. |

Loved this article. great pictures and so much information! Of course it brought back my own special memory with you and the family at a base ball game at The Ramsey House. I hope we can do it again!