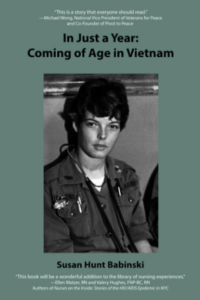

Earlier this year, Appalachia Bare published an article written by Rebecca Williams Mlynarczyk entitled “Oak Ridge.” I was absolutely delighted to meet Rebecca and her family when they came to East Tennessee. Our conversation turned to stories about the Vietnam War. I spoke about my father who journaled about his experiences in Vietnam. She spoke about her friend, Susan Hunt Babinski, who wrote a book about her experiences as a nurse during the war. Babinski’s book, In Just a Year: Coming of Age in Vietnam, was posthumously published by Purple Breeze Press in 2023.

Earlier this year, Appalachia Bare published an article written by Rebecca Williams Mlynarczyk entitled “Oak Ridge.” I was absolutely delighted to meet Rebecca and her family when they came to East Tennessee. Our conversation turned to stories about the Vietnam War. I spoke about my father who journaled about his experiences in Vietnam. She spoke about her friend, Susan Hunt Babinski, who wrote a book about her experiences as a nurse during the war. Babinski’s book, In Just a Year: Coming of Age in Vietnam, was posthumously published by Purple Breeze Press in 2023.

Appalachia Bare would like to celebrate Veterans Day by featuring excerpts from Babinski’s book. Though she is not technically Appalachian, Babinski is one of our nation’s heroines who served in the pediatric ward of the U.S. Army’s 91st Evacuation Hospital during the Vietnam War. Join us as Appalachia Bare honors and acknowledges our veterans and our active military. And we are so grateful for their service. — Delonda Anderson, Chief Editor

“Sandy Beaches, Pumpkin, and Ronald Colman”

As the chopper skimmed the ground, I saw the darkness below erupt into flashes of fire from predawn mortar attacks. There was no way to know who was firing at whom. Above the sound of the chopper engine, I could hear cracks and pops—gunfire directed at us. At the first glow of dawn, those sounds stopped. The soldiers were retreating from the territory, and for a few hours the area belonged to the people again.

It was early morning, and the sun was low in the sky. Joan leaned out of the chopper and began snapping pictures. In her excitement, she nearly fell out, catching herself just in time. Her camera case wasn’t so lucky. We watched it float down into the China Sea. We flew over a dark green mosaic of rice paddies. The shadow of our chopper also fell over Vietnamese farmers working in the fields, dressed in black shirts and pants, walking slowly after their lumbering oxen. None of this seemed real to me. I felt as though I was watching a travelogue.

Suddenly we touched down at the 91st Evacuation Hospital. I snapped out of my reverie and looked around. The entire compound was only ten to fifteen acres. It extended a few hundred yards along a beach. Then there was barbed wire, more sand, a little village, then more sand. The only trees were a couple of scraggly palms a few feet high. Otherwise, there was no green at all. Joan stared at the sand and water with a big grin on her face.

“It’s a heck of a lot better than Saigon.”

I was tired and dirty and pissed at the army or myself—I was not sure which—for sending me to this hell, but I had to admit the blue water looked lovely. I had pictured teeming hospital wards, wounded GIs, bullets flying around us, but I had never imagined stepping into a brochure for a Caribbean island.

A young corpsman met us at the helicopter, took us and our duffle bags containing precious makeup and fatigues to our hooch, and dropped them off in our rooms. He said he would be outside the hooch for five minutes in case we wanted to freshen up before going to headquarters to sign in.

All GI housing and buildings were called hooches, whether they were prefabricated metal Quonset huts or wooden “jungle huts.” Our hooch was wooden with a metal roof. I had been looking forward to living in a tent, which seemed very romantic to me, but instead I would be in a wood hut with a tin roof.

I took a quick look at this bare eight-by-ten-foot cubicle that was to be my home for the next year. We rated our little space because we were officers. It had a cement floor, bare walls with one nail for a hook, an army cot with mosquito netting, and a deflated rubber mattress. At least I had a room to myself.

Then I saw something that really cheered me up. In Saigon, Liddy had to use a toilet that was a hole in the ground with a wooden plank on either side. I had imagined lots of odd things about Nam but never imagined myself standing over a hole full of feces to defecate. Here in hell and gone there were real toilets. How wonderful! They flushed! And there were also indoor individual showers. I quickly brushed my teeth with bottled water.

Several of our hooch mates introduced themselves and welcomed us. They were all close to our age. Their tans told us they had been here a while. One nurse explained that this was a junior hooch, where they put all the younger nurses. Then she opened the back door to show us how close we were to the clean white sand, the bright blue sky, and the sight and sound of the ocean waves. She explained that lifeguards were assigned during the quiet times, when swimming was allowed. Coming from Rhode Island, Joan and I both loved the ocean.

Soon it was time to go. A corpsman was waiting to take us over to headquarters. We found him lounging against the sandbags outside. He immediately flipped his cigarette away. As we walked, he told us that Agent Orange, a defoliant, was regularly spread around the fence. The chemical was known to make people sick, so it was used to keep the Viet Cong out and to prevent Vietnamese girlfriends of some staff members from sneaking onto the compound. It was also spread around some of the nurses’ barracks to eliminate a buildup of foliage.

As we approached the headquarters, I asked the corpsman what he thought of the chief nurse.

“She’s okay but strict with the nurses, I hear. They call her Pumpkin.”

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“You’ll see,” he said.

The base was quiet and the air cool.

“In you go.”

He opened the door but would not come in with us. The woman at the desk didn’t notice us but sat scowling at her paperwork, furiously shuffling papers and jotting down notes. Our rosy-cheeked chief nurse was just under five feet tall and about as wide. Now we understood her nickname. “Colonel Skodova” was the name on her fatigues.

She was about fifty, ancient by our standards. She stopped rustling papers to scrutinize us as we stepped in and gave the mandatory salute. Our shiny new second lieutenant bars indicated we were just out of school. Joan and I were both small and had often been mistaken for high schoolers. I could tell from the look on her face that she was wondering what we were doing here. What was she going to do in the middle of a war with these two children? When we told her our ages, she just shook her head and muttered, “The gold dust twins.” We had no idea who they were, and we were not about to ask.

“Ready to meet your commander?”

Before we could answer, she stood up and took us into the next room to meet the commanding officer of the 91st. He welcomed us and passed us back to Colonel Skovoda, who would fill us in on our assignments and the regulations. Back in her office, she read the long list of regulations of proper nurse behavior. As she spoke to us, she kept removing imaginary lint from our fatigues. It drove me crazy. I kept flinching but that didn’t stop her.

“Let’s take a tour,” she said while showing us the door. She marched us back across the compound into the hospital units, introducing us to nurses, doctors, and corpsmen. Everyone was in olive drab fatigues and combat boots. The only jewelry allowed to show were watches and chains with dog tags. She chatted about people, supplies, and the different wards, acting as though this might have been our first day in any hospital in the States.

Set up by the military to take care of war casualties, the 91st Evacuation Hospital was the first of its kind in Vietnam. Twenty units, each housed in a separate wooden hooch, holding about two hundred patients and fifty nurses. Colonel Skovoda cheerily explained that the army separated the units so that if the compound were hit, the entire hospital would not be destroyed. Sandbags lay everywhere, layered like rock walls around the sides of the hospital units. Half-buried bunkers surrounded the units and our living quarters. Because we had a helicopter unit, we were a target of the Viet Cong, who were focused on destroying the choppers.

She rushed us through the medical and surgical intensive care units, the emergency room, the operating and recovery rooms, and the graves registration unit. A cement sidewalk with a tin roof and a wooden railing connected all the units. A narrow unpaved road separated the hospital from our living quarters, which were built on the beach. Beyond our hooches lay only sand and blue ocean. About two hundred yards to the right of the officers’ quarters, separated by barbed wire and mines and guarded at night by soldiers in a lookout tower, stood a small Vietnamese village. About a mile or two away on the left was the beginning of the jungle.

The 91st was an all-purpose hospital. There was a unit for wounded ARVN (soldiers of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam) and ROK (Republic of Korea) patients. Of course, GIs were also sent to the 91st. If their wounds were minor, they would not be out of action for long.

The place was crawling with 173rd Airborne troops. They wore camouflage gear when visiting their wounded buddies. I never got used to being saluted, and these men never seemed to forget. They were young and serious, always snapping salutes and repeating their motto: “Airborne all the way, ma’am.” Sometimes they shortened the motto to just “Airborne, ma’am.” The spunkier ones smirked and saluted, saying, “All the way, ma’am,” clearly alluding to more than their undying loyalty to the 173rd. I just smiled and half-saluted back.

As we walked from unit to unit, we became aware of the noise of choppers overhead. They were from a Dust Off unit (air ambulances called Helicopter Ambulance Medevac Units) attached to the hospital. The sound was ominous. No matter what you were doing, you would pause for a second to listen, not because of the noise but because of what it meant. Wounded were coming in. When a chopper left and returned quickly with wounded, you realized how close you were to the fighting.

We stopped in the pediatric unit full of Vietnamese children injured by the war. What shocked me most was the size of the children and young adolescent patients. So many were so tiny and so sad-looking. Maybe this is how it would have looked if all the American children in a pediatrics unit had been in bad car accidents. Their bodies were wrapped in gigantic bandages. Often their arms and legs were in casts or splints. Their huge, serious, solemn eyes peered from their undernourished faces. I remember thinking, These are children. They had no place in a war zone. Standing there looking at the children, my heart melted, and all I wanted to do was stay. But Colonel Skodova was getting anxious for us to move along.

Some units had Vietnamese women to help, cleaning up after the doctors and nurses, washing instruments to go back to the OR for sterilization, straightening out cots, chatting with patients, and generally keeping them comfortable. Everyone called them mamasans, a GI term for a married Vietnamese woman that may have come from the Second World War but now referred to any local woman.

We stopped and rested for a bit. The Colonel had a lot of energy, but the heat bothered her, and sweat dripped from her face. “It gets to be 120 degrees in the shade, you know,” she groaned. She asked us what unit we wanted to work in. I felt she was being courteous and probably already knew where she wanted us placed. But without hesitation, I said pediatrics.

“Wonderful,” she said. “Most nurses think pediatrics is a punishment. They want to work in intensive care or PreOp with the GIs and the air conditioning.” She sighed as she mopped her face with a large olive drab handkerchief.

She assigned Joan to the medical intensive care unit, the one with the GIs. Joan could not believe her luck. We soon learned that every nurse without a specialty rating was rotated through ICU so that the head nurse, Major Gorman, could check her out and then move her elsewhere on the compound. Major Gorman? Joan and I looked at each other. Could it be?

Major Gorman turned out to be the same person who was in our basic training class at Fort Sam Houston. She was almost six feet tall, thin, wore round metal-framed glasses, and spoke with a Boston accent. When we first met her, Joan, a veteran of the Catholic school system, whispered, “Here comes Mother Superior.” First impressions may be wrong, but in eight weeks of basic training we had seen her smile twice. This was no warm reunion. “Hello” and a slight nod was all we got from Major G . . .

![]()

“Sunrise and Censure”

The attacks usually wouldn’t start until late, after midnight. There would be gunshots, the rhythmic thumping of mortar fire, and the whistling of heavy artillery. Either our base was under attack, or the air strip or some groups of men were getting fired upon. The sounds went on and on. Sometimes we saw red flares shoot up—a red alert—meaning the enemy had infiltrated our perimeter. Somewhere, close by, enemy soldiers were coming. The shelling intensified, and we waited for it to stop.

By the end of summer, the red alerts came more frequently and seemed to go on longer. We now had to wear heavy flak jacket vests and metal pot helmets. But I still didn’t feel that I was in danger. I was surrounded by an army. What could happen to me? My personal sense of safety was only shaken when an Air Force officer handed me a handgun and urged me to keep it in my room in case Viet Cong came in the door.

Whenever there was a red alert, all the hospital units with burlap windows would be in mandatory blackout. You had to stumble around in the dark with only a dim flashlight, gathering the children and putting them on the floor under their beds. For a while, the red alerts happened every night. They became so common that we would routinely go around at bedtime, putting the children on the floor, arranging pillows and blankets to make the hard, ungiving cement as comfortable as it could be.

Then we just watched the children, sat with them if they woke up, changed bandages, gave out meds, checked dressings, took temps and blood pressures, and smoked endless cigarettes while, through the burlap windows, we watched the red flares shoot into the sky near us and gently sail down, lighting up the ground. We sat and talked and smoked and waited—there was nothing else to do. At last we would hear a great whoosh, the noise of the white flares being shot off to tell us all was well. At other times nothing happened until the first glow of dawn appeared. Then the thumping of the guns stopped, and we got busy with our routines on the unit.

Charlie and I were a team. He never seemed uncomfortable about my being an officer or angry about my privileged position. We became quicker and quicker at changing dressings together. Carried away by the night and our efficiency, we began to play out little scenarios. He was a doctor. I was a doctor.

“Well, Dr. Kildare, what do you make of this?”

“What idiot did this suturing? I’ll have him run out of the profession.”

We made faces and pantomimed so the children could join in the fun. I watched Charlie change a dressing on a girl’s leg that had been badly burned. It was a beautiful job. He not only made a neat dressing, but he treated the girl gently and carefully.

“Beautiful, Her Doktor!” giving my impression of a Viennese physician.

“Danke schön.”

Charlie winked and managed to click his heels while still bent over, wrapping the dressing. The girl was eleven or twelve and began to giggle. He smiled and immediately clicked his heels again.

“But of course, Doktor. What else would you expect?”

Sometimes we even managed to forget to think about the gaping infected wounds we were so carefully tending.

Around dawn, when we were cleaning up, changing the children’s bedding, getting ready for the change from the night to the day shift, Charlie would take out the honey bucket, dump it, and rinse it outside at a pipe with running water. With the door open, the morning light flooded into the hooch.

One morning Charlie called me out back to see something. There it was—the sunrise. I had never seen such a sunrise before. So many colors. So brilliant. We leaned on the railing of the ramp outside the open back door and watched the sun rise while sharing a cigarette. The children who could walk came over and stood with us, watching the sunrise silently with us. It was quiet and cool outside, with a mild morning breeze caressing our faces. This was the coolest part of the day. The only heat we felt was from the closeness of our bodies.

From that day on, when I worked nights with Charlie, we always watched the sun come up. It became a ritual, and we worked out a system. We would try to get everything done, everyone washed and cleaned up a little earlier. The children and the mamasans understood and pitched in to help finish on time so that we could all have our five minutes of bliss together.

Charlie and I and whichever patients were able, and probably some who should not have gone outside because they were on bed rest, would go out the back door of the hooch. We put Kim, the lower half of her body still covered with a large cast, onto a gurney and wheeled her out so she could watch the sunrise with us. Sometimes she hummed softly while we watched, other days she just watched in silence with the rest of us.

We all sat close together on the ramp, hunkered down the Vietnamese way, or we sat on the wooden guard rails as we watched the sun rise. Charlie and I shared cigarettes with the mamasan patients. We could not communicate in many ways, but the shared cigarettes and watching the sunrise together were communication. To an outsider, we would have looked like a motley crew. But for at least those few minutes, we were one beautiful family. No matter what happened at night, no matter what terrors we felt yesterday, everything was washed clean for a minute while we shared the sweet morning wind, the sunrise, and a cigarette.

The sun was up and so were the children. Time to recheck dressings for drainage and add finishing touches to grooming—a braid in a little girl’s hair, new used clothing from the States. I loved to dress the children in my brothers’ outworn shirts and pants, which my family sent me. It was strange to see the children in my little brothers’ clothing. It made me love the Vietnamese children even more. It made them more familiar. The children liked it too, or maybe they liked it because I liked it. I missed my little brothers. Most of all when I saw those cute big-eyed children strutting around in my brothers’ plaid shirts . . .

When Susan Hunt boarded a plane to Saigon in the summer of 1967, she was twenty-two years old. After graduating from the Rhode Island Hospital School of Nursing, she enlisted in the US Army and volunteered for a one-year tour of duty in Vietnam. She hoped to work with children, a dream that came true when she was assigned to the pediatric unit of the 91st Evacuation Hospital in Tuy Hòa.

Soon after arriving back in the United States in 1968, Second Lieutenant Susan Hunt resigned her commision in the Army. Her pediatric career continued. She earned a master’s degree in child and adolescent psychiatric nursing. She earned her PhD in applied psychology. While attending the dedication of the Vietnam Women’s Memorial on the National Mall in 1993—an event of immense significance for nurse veterans like Babinski—she learned that the 91st Evacuation Hospital, where she served, had been declared an Agent Orange Center. She was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2016 and died in 2018 at the age of seventy-three.

Purple Breeze Press is offering a special deal for Susan Babinski’s book, In Just a Year: Coming of Age in Vietnam. In honor of Veterans Day, readers can purchase Babinski’s Kindle book on Amazon for 99 cents. The deal lasts through November 17. Take advantage of this generous offer! Click on the book cover image below:

**Featured image: 36th Medical Evacuation Hospital, 1968/ SP5 Ronald Delaurier, U.S. Army — Wikimedia, public domain

![Lieutenant Junior Grade K. Saunders, Nurse Corps, U.S. Navy, and [[V.C.Charlie]], an injured Vietnamese child. USS Sanctuary, Vietnam, 1967, Navy Medicine, Snappygoat via Flickr](https://wp-modula.b-cdn.net/spai/q_glossy,ret_img,w_600,h_600/https://www.appalachiabare.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Lieutenant-Junior-Grade-K.-Saunders-Nurse-Corps-U.S.-Navy-and-V.C.Charlie-an-injured-Vietnamese-child.-USS-Sanctuary-Vietnam-1967-Navy-Medicine-Snappygoat-via-Flickr-600x600_c.jpg)