Welcome back to Part 2, the last of Appalachia Bare’s series about the Daugherty surname. Our focus here will mainly be on Sir Cahir Rue O’Doherty, the last Gaelic/ Irish Chieftain. Understandably, Cahir is not from Appalachia. But I remember something my grandmother once said to me: A Daugherty is a Daugherty. We’re all kin. Just a note: I’ve done quite a bit of research on the Daughertys for several years and my mother did so before me. So, my findings are heavily sourced.

I. A Promising Beginning

So, we pick up at the point where Cahir’s foster family, the MacDavitts, persuaded Sir Henry Docwra to take in the young lad and show him the proverbial English ropes in exchange for the MacDavitts’ loyalty and service to the crown. That Cahir was in agreement with the proposal is evident. He weighed his options. On one side, Red Hugh O’Donnell and his clan planned to “relegate him to obscurity” and employ his uncle Felim O’Doherty as a sort of general-king “who could lead the men of Inishowen into battle against the English.”1)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. On the other side, the English “would make [Cahir] Lord” of Inishowen, a title for which the boy had been designed and prepped all his life. Cahir was designated the new Chieftain of Inishowen in 1601.2)Doherty, Jack and Sarah. n.d. “The O’Doherty Rebellion 1608.” Walking to Donegal. Accessed Mar 2021. In 1603, Docwra procured a further deal for Cahir in Inishowen, which “reserved to the crown, Culmore Castle, the fishings, and 300 acres of land.”3)Healy, T. M. 1913. Stolen Waters: A Page in the Conquest of Ulster. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. What this basically meant was that O’Doherty could retain these holdings as long as England said he could. Should the Crown decide to give these “gifts” to someone else, they could. And they did. In January 1605, O’Doherty was regranted the holdings only to have them given in May to a Captain Hart to lease for “21 years at 10 shillings a year.”4)Healy, T. M. 1913. Stolen Waters: A Page in the Conquest of Ulster. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. This wound was the first metaphorical knife to his back.

O’Doherty enjoyed a good relationship with Sir Henry Docwra. He was like a father to Cahir, who reared, trained, taught, and advised him every step of the way. O’Doherty became Docwra’s “right hand man” at the tail end of the Nine Years’ War. In later years, Docwra admitted that English victory would have been “‘utterly impossible’”5)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. without Cahir, writing:

O’Doherty was with me, slighted when I did, kept me company in the greatest heat of the fight, behaved himself bravely, and with a great deal of love and affection; so much so, that I recommended him, at my next meeting with the lord deputy Mountjoy, for the honor of knighthood, which was accordingly conferred on him.6)Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. p. 287

O’Doherty received knighthood by the Queen’s deputy, Lord Mountjoy, in 1602.7)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine.

It should be noted that England’s “military campaign in Ulster was murderous.” Documents list the murder of “countless” Irish men, women, and children. Houses and food supplies were burned, and livestock was appropriated or butchered. Sir Arthur Chichester “boasted that he and his men ‘killed man, woman, child, horse, beast and whatsoever we found.’” The same Mountjoy who knighted Cahir said “even the best Irish people were ‘in their nature little better than devils.’”8)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. That Cahir sided with the English, helping the Irish to lose the Nine Years’ War, surely stuck in the craw of O’Doherty’s countrymen. To be fair though, up to that time (around 1600-1603), the Irish had no qualms fighting between and amongst themselves. Power and kingship over certain regions constantly changed hands. They were, it seems, accustomed to betrayal from one another.

II. Things Become Problematic

At the end of the Nine Years’ War, Queen Elizabeth I died and James I became king. O’Doherty “accompanied Mountjoy” for an audience with the king. At this meeting, James I formally gave Cahir “his father’s titles and lands” with a proviso that he would forfeit his estate if “any act of treason, or of rebellion” occurred.9)Cuninghame, Richard. 1904. The Broken Sword of Ulster: A Brief Relation of the Events of One of the Most Stirring and Momentous Eras in the Annals of Ireland. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis & Co., LTD. P. 175 When he returned to Ireland, he married Mary Preston, daughter of the 4th Viscount Gormanston10)Viscount was somewhere between an earl and a baron. Christopher Preston. King James I “was well pleased” because the Preston family had been staunch English loyalists since England first had its eye on Ireland.11)Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. pgs. 287-288 The marriage enabled O’Doherty to join leagues with the 1st Vicount FitzWilliam and Niall O’Donnell, cousin and “rival”12)O’Doherty’s Keep. 2017. “Sir Cahir O’Dochairtaigh.” O’Doherty’s Keep. Accessed Mar 2021. to Hugh O’Donnell, mentioned in the first post, “The Blood of Dochartach.”13)Niall was incensed that his cousin Hugh O’Donnell was awarded chieftain and the two became bitter enemies. Niall was a cunning and sneaky man, in my opinion much like Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello, who was talented at planting little tidbits in the mind and deceiving others to gain their trust, only to betray persons in the end. This union was an Irish noble trifecta of English support.14)O’Doherty’s Keep. 2017. “Sir Cahir O’Dochairtaigh.” O’Doherty’s Keep. Accessed Mar 2021. O’Doherty “had ambitions to become a courtier . . . in the household of Henry Fredrick, Prince of Wales,”15)O’Doherty’s Keep. 2017. “Sir Cahir O’Dochairtaigh.” O’Doherty’s Keep. Accessed Mar 2021. a position close to the crown that would further protect his properties and resources “against covetous British officials in Ireland.”16)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine.

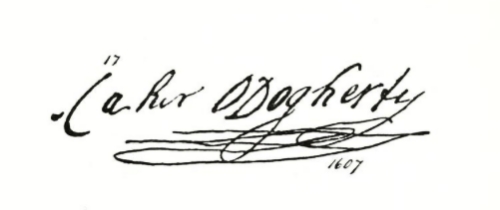

A trial was held after the Flight of the Earls in 1607. Cahir was made “the foreman of the jury that found [the parties] guilty of high treason.”17)Webb, Alfred. 1878. “Sir Cahir O’Dogherty.” In A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M.H. Gill & Son. He accepted the post “to strengthen his position” inside the Crown’s establishment18)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. after some political opposition we’ll discuss later. Somewhere between 1606 and 1607, O’Doherty’s English father-like figure, Sir Henry Docwra, “sold his position” as Derry’s governor to Sir George Paulett.19)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. After Docwra’s departure, it didn’t take long for land-hungry, covetous eyes to laser in on the young twenty-year-old. O’Doherty’s land was the second largest territory in Inishowen20)Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. p. 281 with lush and bountiful soil. He had several castles, the most famous of which were Elagh (where he reportedly stayed), Burt, and Buncrana.21)Webb, Alfred. 1878. “Sir Cahir O’Dogherty.” In A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M.H. Gill & Son. Everyone from Chichester to Paulett to George Montgomery (“the first Protestant bishop of Derry, Raphoe, and Clogher”)22)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. wanted O’Doherty’s land – and they’d do anything to get it. Plots and conspiracies to take away everything “O’Doherty” ensued.23)O’Dochartaigh, Seoirse Fionnbarra. 1998. O’Doherty People and Places. Whitegate, Co. Clare: Ballinakella Press. p. 22 The schemes themselves become quite confusing, which, I’m guessing is exactly what the greedy men wanted.

As mentioned before, Chichester was no fan of the Irish. Paulett took an arguably worse mindset as he was “an irascible character”24)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. and “a man of violent temper, rude and overbearing”25)Cuninghame, Richard. 1904. The Broken Sword of Ulster: A Brief Relation of the Events of One of the Most Stirring and Momentous Eras in the Annals of Ireland. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis & Co., LTD. p. 176-177 who “had little respect for Catholics or the Irish.”26)McGuigan, Cathal. 2016. “On This Day in 1608 – Derry burned to the ground in O’Doherty’s Rebellion.” The Irish News. April 19. Plus, he didn’t like the deal Docwra left him in Derry.27)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. Paulett definitely didn’t like Irishmen who thought their positions were equal or superior and he often publicly humiliated them – verbally and physically. A few months after Docwra left, Bishop Montgomery sued O’Doherty in the king’s court for Inishowen lands.28)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. Not long after the Flight of the Earls, and even after O’Doherty’s service as foreman on the jury, Paulett got wind of several rumors. One allegation was “that Sir Cahir was planning to rebel – which was most unlikely.”29)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. Paulett then tried to seize O’Doherty’s main castle at Burt.30)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. Another rumor was that Cahir considered “leaving Ireland without proper licence [sic], which was then a treasonable offence.”31)Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. p. 290 Cahir had sold 3,000 acres of land to Sir Richard Hansard in 1607 or 1608 “who intended to ‘inhabit’ the land” and Cahir needed Paulett’s signature on the deed.32)Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. Conspiracy theories abounded. O’Doherty immediately sought Chichester’s counsel to dissuade the rumors, but he was stunned when Chichester held him under suspicion and “insisted that the Irish lord provide sureties to guarantee his loyalty.” O’Doherty refused, viewing this “as an affront to his record of service to the crown.” He was summarily “imprisoned in Dublin Castle until he complied.”33)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. Seoirse Fionnbarra O’Dochartaigh in O’Doherty People and Places (1998) mentions yet another slight the Englishmen perpetrated against O’Doherty. They gave fishing rights over all Donegal Bay to a Captain Bingley “without consultation.” The captain would also have complete control over the entire River Swilly with Inch Island as “his centre of operations.”34)McDevitt, Rev. Dr. 1894. The Donegal Highlands: Recast and Enlarged. Dublin: Sealy, Bryers and Walker. This entire area was “traditionally the exclusive and legitimate domain of the O’Dohertys.”35)McDevitt, Rev. Dr. 1894. The Donegal Highlands: Recast and Enlarged. Dublin: Sealy, Bryers and Walker. All these efforts to delegitimize Cahir and the O’Doherty surname piled one atop the other and culminated with an event that would change the course of history for the O’Dohertys, Ireland chieftainship, and, arguably, Ireland herself.

III. It Hits the Fan

O’Doherty was on his way to either retrieve Paulett’s signature or discuss some other matter with him in April 1608. The venue was a public function where Cahir was to be honorably received.36)O’Dochartaigh, Seoirse Fionnbarra. 1998. O’Doherty People and Places. Whitegate, Co. Clare: Ballinakella Press. p. 22 Paulett was obnoxiously arrogant and the men argued. When O’Doherty said “‘I think myself as good as you,’”37)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. Paulett, “in a fit of rage and frustration,”38)Harris, F. W. 1980. “The Rebellion of Sir Cahir O’Doherty and its Legal Aftermath.” Irish Jurist p. 298-325. charged O’Doherty with treason and either “struck him violently with his clenched fist”39)Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. p. 290 or slapped him across the face.40)Doherty, Jack and Sarah. n.d. “The O’Doherty Rebellion 1608.” Walking to Donegal. Accessed Mar 2021. The affront, remember, was in public view in Derry. That Cahir was livid was an understatement. Who wouldn’t be? Instead of initially reacting, O’Doherty took to his horse and rode furiously to seek counsel from his foster family, the MacDavitts. Cahir was advised to act in one of two ways:

-

Offer Paulett a large sturgeon as a “peace offering.” Since the 1400s, the sturgeon was considered a “royal fish” because, if it was caught in Irish waters, it “had to be given to the King or Queen.”41)The sturgeon sometimes weighed more than 60 pounds, but the fish is now extinct in Ireland. The last record was in 1967 and it weight 29 kg., or 63.93 pounds.

-

Burn Derry to the ground.

Cahir chose the first option. After Paulett received the sturgeon, however, he mocked O’Doherty and said scornfully within ear shot of Inishowen “ambassadors”: “‘The Irish are like spaniels, the miserable curs! The more you whip them, the more they will fawn on you.’”42)Young, Robert S. 1897. “Archaeological Rambles in the Inisowen Mountains.” Ulster Journal of Archaeology 196-199. p. 197 Robert S. Young in his piece “Archaeological Rambles in the Inisowen Mountains,” wonders whether Paulett’s treatment was to “drive [Cahir] into rebellion” so they could ultimately be rid of the chieftain and confiscate his lands. I think so. The theory is certainly plausible. And it worked. Cahir became “disillusioned with the reality of British rule”43)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. and his relationship with the English Crown deteriorated. Again, he sought council from the MacDavitts who “declared that the insult could be wiped out only with blood.”44)Webb, Alfred. 1878. “Sir Cahir O’Dogherty.” In A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M.H. Gill & Son. Cahir’s foster brother, Phelim Reagh MacDavitt, also received violent treatment from “agents of the crown” and was ready to “avenge the insults.”45)Harris, F. W. 1980. “The Rebellion of Sir Cahir O’Doherty and its Legal Aftermath.” Irish Jurist 298-325. p. 300 News of Paulett’s treatment of O’Doherty spread throughout the region and the people of Inishowen were at the ready “whenever Sir Cahir gave them the signal.”46)Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. pgs. 290-291 Cahir then went to Niall O’Donell who advised him to “seize Culmore . . . and other strong places” to amass weaponry, then “march on Derry, and massacre the English settlers in the market-square.” Niall promised reinforcements when the time came. The MacDavitts backed the plan.47)Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. pgs. 291-292

IV. O’Doherty’s Rebellion

O’Doherty took action almost immediately. He invited Captain Hart of Culmore (the same Hart the English gave O’Doherty’s castle, fishing rights, and acreage) and Hart’s family to Castle Elagh in the guise of an entertaining evening. Instead, he apprehended the Harts, and, on April 18, 1608,48)Harris, F. W. 1980. “The Rebellion of Sir Cahir O’Doherty and its Legal Aftermath.” Irish Jurist 298-325. “started at dead of night for Culmore, surprised it, butchered the garrison, and sacked the place.”49)Webb, Alfred. 1878. “Sir Cahir O’Dogherty.” In A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M.H. Gill & Son. Culmore held a great amount of munitions, which O’Doherty and his men took to use at Derry.50)Derry was originally formed “on an island” (Young, Robert S. 1897. “Archaeological Rambles in the Inisowen Mountains.” Ulster Journal of Archaeology 196-199. p. 196) and was “in the hands of the native Irish,” specifically the O’Doherty, O’Donnell, and O’Cahan clans. In Irish, the name means “a place of oaks.” (Geoghegan, Arthur Gerald. 1863. “A Notice of the Early Settlement, in A. D. 1596, of the City of Derry by the English, to Its Burning by Sir Cahir O’Doherty, in A. D. 1608.” The Journal of the Kilkenny and South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society.) He took 100 armed men and arrived at Derry well before dawn (2:00 a.m.) on April 19, 1608.51)Webb, Alfred. 1878. “Sir Cahir O’Dogherty.” In A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M.H. Gill & Son. The first place they headed was to Paulett’s house, who was immediately “hacked to death with the pikes and skeans of Owen O’Doherty and others of [Cahir’s] kindred.”52)Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. p. 294 The Annals of the Four Masters, written from 1589-1616 records the slaying thusly:

The Governor was slain by Owen, the son of Nial, son of Gerald O’Doherty, and Lieutenant Corbie by John, the son of Hugh, son of Hugh Duy O’Donnell. Many others were also slain besides these.

O’Doherty’s men next arrived at the covetous Bishop Montgomery’s place, where his library was burned down.53)Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. p. 294 Hundreds of treasured volumes and documents were destroyed. The remaining captured persons “negotiated with O’Doherty and were allowed to leave, relatively unharmed.54)McGuigan, Cathal. 2016. “On This Day in 1608 – Derry burned to the ground in O’Doherty’s Rebellion.” The Irish News. April 19. O’Doherty and his men pillaged, plundered, and burned Derry down, “leaving only ‘chimneys and some stone walls standing.’”55)McGuigan, Cathal. 2016. “On This Day in 1608 – Derry burned to the ground in O’Doherty’s Rebellion.” The Irish News. April 19. Hostages were also taken and jailed at O’Doherty’s Castle Burt.56)Doherty, Jack and Sarah. n.d. “The O’Doherty Rebellion 1608.” Walking to Donegal. Accessed Mar 2021. This attack turned out to be the apex of O’Doherty’s Rebellion. A short time later, Strabane was also burnt to the ground. O’Doherty and his followers were determined to succeed. They used his castles for strategy discussions and as “defensive strongholds.”57)Doherty, Jack and Sarah. n.d. “The O’Doherty Rebellion 1608.” Walking to Donegal. Accessed Mar 2021. O’Doherty pressed forward and made several unsuccessful attacks in other Donegal regions. By this time, Chichester had mustered “all available forces both of horse and foot.”58)Harris, F. W. 1980. “The Rebellion of Sir Cahir O’Doherty and its Legal Aftermath.” Irish Jurist 298-325. He made certain the English retook Derry on May 20th. Commander Sir Richard Wingfield took Castle Burt on July 1, freed the prisoners held there and captured his own prisoners: O’Doherty’s wife and child.59)Mary Preston’s kinsmen requested the Irish government to assist her, especially since O’Doherty’s Rebellion caused the forfeiture of all his lands and assets. Chichester agreed and gave her a small pension. She later remarried. No one knows what happened to Cahir’s child. He did have two brothers, John and Rory. At the time of the rebellion, John was with his foster-father, far from the happenings. Rory, however, was captured but later released because he was too young to take part in the insurrection. Both boys were reared in a loving home and went on to have successful lives. – information from The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, and Death in Exile by The Rev. C. P. Meehan (1870) O’Doherty was no match against the formidable English army. The very man who urged Cahir to rebel and promised his backing, Niall O’Donnell, switched sides and “supported the English . . . in the hope of some reward.”60)Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. Speaking of reward, Chichester made a disturbing but masterful move, publishing a proclamation that pardoned anyone who “laid down their arms”, turned in the rebels, or killed their comrades, with exception of Phelim MacDavitt, who had “no hope of mercy.”61)Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. p. 295 Though he and his men fought bravely, and tried to retreat to save himself and his followers, O’Doherty was eventually forced into battle at Kilmacrenan on July 5, 1608, where, he was shot in the head on July 18th and died “almost instantly” on Doon Rock. The rest of O’Doherty’s men scattered, except his foster brother, Phelim Reagh who “never abandoned” O’Doherty’s body until he had to leave for his own “self preservation.”62)Healy, T. M. 1913. Stolen Waters: A Page in the Conquest of Ulster. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 296 O’Doherty’s Rebellion lasted only eleven weeks.

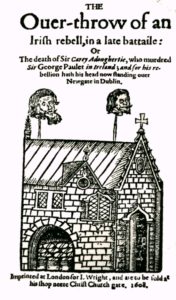

V. Aftermath and Closing

The English immediately cut off Cahir’s head and displayed it on a pike in Dublin, “on the east gate of the city, called Newgate.”63)Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. p. 296 He was further “cut into quarters between Derry and Cuil-mor”64)Author, Unknown. 1589-1616. “Annals of the Four Masters.” CELT: The Corpus of Electronic Texts. Accessed Mar 2021. and his body parts were “‘put up for signs.’”65)Harris, F. W. 1980. “The Rebellion of Sir Cahir O’Doherty and its Legal Aftermath.” Irish Jurist 298-325.

Because he rebelled, all O’Doherty’s lands and assets were forfeited to the Crown. After the rebellion, some rebels were captured and immediately executed. Others were tried, found guilty, then executed. Still more were “considered undesirable” and “were shipped off for service in the army of the king of Sweden.”66)Harris, F. W. 1980. “The Rebellion of Sir Cahir O’Doherty and its Legal Aftermath.” Irish Jurist 298-325. p. 303 Almost all of them turned on each other for money. O’Doherty’s foster brother, Phelim Reagh was captured and “examined.” During these “examinations,” Reagh revealed that Niall O’Donnell met with O’Doherty before the Derry incident and said Niall “had ‘earnestly labored and persuaded [Cahir] that . . . he should burn the town and massacre the people.’” Phelim also told his examiners that Niall kept promising O’Doherty he’d join his rebellion with reinforcements, both of which never came.67)Harris, F. W. 1980. “The Rebellion of Sir Cahir O’Doherty and its Legal Aftermath.” Irish Jurist 298-325. p. 313 Niall and his son were subsequently sent to the Tower of London where they remained until they died.68)Author, Unknown. 1589-1616. “Annals of the Four Masters.” CELT: The Corpus of Electronic Texts. Accessed Mar 2021. And what of O’Doherty’s land? On June 30th, 1609, James I gave Cahir’s lands to Chichester who “took custody of Culmore Castle.”69)Healy, T. M. 1913. Stolen Waters: A Page in the Conquest of Ulster. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. Other O’Doherty properties were now in the King’s possession. They would consequently “be planted with English and Scottish landlords and settlers.”70)Doherty, Jack and Sarah. n.d. “The O’Doherty Rebellion 1608.” Walking to Donegal. Accessed Mar 2021.

Some sources have said that Cahir was “stupid” or “ignorant” or “blind.” I would argue that perhaps Red Hugh O’Donnell was right – that Cahir was too young to be a chieftain at this time, but O’Donnell’s way of dealing with the situation (ignoring Cahir altogether) was wrong and unfortunate. Cahir was taught the Gaelic/Celtic/Irish ways for the first 13 to 14 years of his life. He was reared to be king. After his father’s death, he was taught England’s way of doing things and learned all-too-harshly that no matter what an Irishman accomplished, no matter what glory or praise he obtained, no matter how loyal he was to the crown, he was still an Irishman and (hand-cupped whisper) . . . a Catholic . . . fateful disadvantages in England’s eyes that sparkled greedily for Ireland itself.

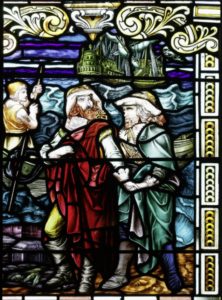

**Featured Image: From Pikrepo

References

| ↑1, ↑5, ↑7, ↑8, ↑16, ↑18, ↑19, ↑22, ↑24, ↑27, ↑28, ↑29, ↑30, ↑33, ↑37, ↑43, ↑60 | Jeffries, Henry A. nd. “Prelude to Plantation: Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s Rebellion in 1608.” History Ireland Magazine. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑40, ↑56, ↑57, ↑70 | Doherty, Jack and Sarah. n.d. “The O’Doherty Rebellion 1608.” Walking to Donegal. Accessed Mar 2021. |

| ↑3, ↑4, ↑69 | Healy, T. M. 1913. Stolen Waters: A Page in the Conquest of Ulster. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. |

| ↑6 | Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. p. 287 |

| ↑9 | Cuninghame, Richard. 1904. The Broken Sword of Ulster: A Brief Relation of the Events of One of the Most Stirring and Momentous Eras in the Annals of Ireland. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis & Co., LTD. P. 175 |

| ↑10 | Viscount was somewhere between an earl and a baron. |

| ↑11 | Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. pgs. 287-288 |

| ↑12, ↑14, ↑15 | O’Doherty’s Keep. 2017. “Sir Cahir O’Dochairtaigh.” O’Doherty’s Keep. Accessed Mar 2021. |

| ↑13 | Niall was incensed that his cousin Hugh O’Donnell was awarded chieftain and the two became bitter enemies. Niall was a cunning and sneaky man, in my opinion much like Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello, who was talented at planting little tidbits in the mind and deceiving others to gain their trust, only to betray persons in the end. |

| ↑17, ↑44, ↑51 | Webb, Alfred. 1878. “Sir Cahir O’Dogherty.” In A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M.H. Gill & Son. |

| ↑20 | Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. p. 281 |

| ↑21 | Webb, Alfred. 1878. “Sir Cahir O’Dogherty.” In A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M.H. Gill & Son. |

| ↑23, ↑36 | O’Dochartaigh, Seoirse Fionnbarra. 1998. O’Doherty People and Places. Whitegate, Co. Clare: Ballinakella Press. p. 22 |

| ↑25 | Cuninghame, Richard. 1904. The Broken Sword of Ulster: A Brief Relation of the Events of One of the Most Stirring and Momentous Eras in the Annals of Ireland. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis & Co., LTD. p. 176-177 |

| ↑26, ↑54, ↑55 | McGuigan, Cathal. 2016. “On This Day in 1608 – Derry burned to the ground in O’Doherty’s Rebellion.” The Irish News. April 19. |

| ↑31, ↑39 | Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. p. 290 |

| ↑32 | Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. |

| ↑34, ↑35 | McDevitt, Rev. Dr. 1894. The Donegal Highlands: Recast and Enlarged. Dublin: Sealy, Bryers and Walker. |

| ↑38 | Harris, F. W. 1980. “The Rebellion of Sir Cahir O’Doherty and its Legal Aftermath.” Irish Jurist p. 298-325. |

| ↑41 | The sturgeon sometimes weighed more than 60 pounds, but the fish is now extinct in Ireland. The last record was in 1967 and it weight 29 kg., or 63.93 pounds. |

| ↑42 | Young, Robert S. 1897. “Archaeological Rambles in the Inisowen Mountains.” Ulster Journal of Archaeology 196-199. p. 197 |

| ↑45 | Harris, F. W. 1980. “The Rebellion of Sir Cahir O’Doherty and its Legal Aftermath.” Irish Jurist 298-325. p. 300 |

| ↑46 | Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. pgs. 290-291 |

| ↑47 | Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. pgs. 291-292 |

| ↑48, ↑58, ↑65 | Harris, F. W. 1980. “The Rebellion of Sir Cahir O’Doherty and its Legal Aftermath.” Irish Jurist 298-325. |

| ↑49 | Webb, Alfred. 1878. “Sir Cahir O’Dogherty.” In A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M.H. Gill & Son. |

| ↑50 | Derry was originally formed “on an island” (Young, Robert S. 1897. “Archaeological Rambles in the Inisowen Mountains.” Ulster Journal of Archaeology 196-199. p. 196) and was “in the hands of the native Irish,” specifically the O’Doherty, O’Donnell, and O’Cahan clans. In Irish, the name means “a place of oaks.” (Geoghegan, Arthur Gerald. 1863. “A Notice of the Early Settlement, in A. D. 1596, of the City of Derry by the English, to Its Burning by Sir Cahir O’Doherty, in A. D. 1608.” The Journal of the Kilkenny and South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society. |

| ↑52, ↑53 | Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. p. 294 |

| ↑59 | Mary Preston’s kinsmen requested the Irish government to assist her, especially since O’Doherty’s Rebellion caused the forfeiture of all his lands and assets. Chichester agreed and gave her a small pension. She later remarried. No one knows what happened to Cahir’s child. He did have two brothers, John and Rory. At the time of the rebellion, John was with his foster-father, far from the happenings. Rory, however, was captured but later released because he was too young to take part in the insurrection. Both boys were reared in a loving home and went on to have successful lives. – information from The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, and Death in Exile by The Rev. C. P. Meehan (1870) |

| ↑61 | Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. p. 295 |

| ↑62 | Healy, T. M. 1913. Stolen Waters: A Page in the Conquest of Ulster. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 296 |

| ↑63 | Meehan, Charles Patrick. 1870. The Fate and Fortunes of Hugh O’Neill, Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donel, Earl of Tyrconnel; Their Flight from Ireland, Their Vicissitudes Abroad, and Their Death in Exile. Dublin : James Duffy, 15, Wellington-Quay. p. 296 |

| ↑64, ↑68 | Author, Unknown. 1589-1616. “Annals of the Four Masters.” CELT: The Corpus of Electronic Texts. Accessed Mar 2021. |

| ↑66 | Harris, F. W. 1980. “The Rebellion of Sir Cahir O’Doherty and its Legal Aftermath.” Irish Jurist 298-325. p. 303 |

| ↑67 | Harris, F. W. 1980. “The Rebellion of Sir Cahir O’Doherty and its Legal Aftermath.” Irish Jurist 298-325. p. 313 |

![[The land and fort of Derry] - oldest map of English colonial Derry December 27, 1600_Fotor650](https://wp-modula.b-cdn.net/spai/q_glossy,ret_img,w_650,h_433/https://www.appalachiabare.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/The-land-and-fort-of-Derry-oldest-map-of-English-colonial-Derry-December-27-1600_Fotor650.jpg)

Another great post, glad to see you had mentioned the soldiers sold to sweden. An honor Torlough would be proud to see. He never returned from sweden, and his family never knew what happened to him. Some research points to the possibility they died fighting Russian imperial forces in the east, even a possibility they survived and established a home there.