Some years ago, my family and I visited former president Andrew Johnson’s home in Greeneville, Tennessee. The tour was interesting, as all historical places are, but I felt a heavy presence throughout the house. Perhaps that feeling had something to do with a sort of transposed shame that Andrew Johnson was a Tennessean, the first president to be impeached, a brazen racist, and, arguably, one of the worst presidents our country has ever had. Or, perhaps the feeling was caused by the home’s lingering ghostly residuals. Houses hold a lot of hurts and secrets.

Johnson and his wife Eliza McCardle Johnson had five children: Martha, Charles, Mary, Robert, and Andrew. That the Johnsons faced several tragedies is an understatement. Eliza battled tuberculosis for most of her life and ultimately succumbed to the disease. Charles died from head injuries after he fell off a horse during the Civil War.1)National Park Service. 2020, Updated. “Andrew Johnson’s Family.” National Park Service. July 4. Robert committed suicide at age thirty-five after suffering for years from tuberculosis and alcohol addiction.2)National Park Service. 2020, Updated. “Andrew Johnson’s Family.” National Park Service. July 4. Andrew also had “tuberculosis and drank to excess”3)National Park Service. 2020, Updated. “Andrew Johnson’s Family.” National Park Service. July 4. and died at the early age of twenty-six. Johnson’s brother, William Patterson Johnson, died in 1865 from an accidental gunshot wound while hunting.4)Havelin, Kate. 2005. Andrew Johnson. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications Company. p. 64

The Johnson house has seen more than a fair share of misery, all locked tidily within. But secrets are locked away, too, and sometimes those secrets become mysteries. I’m reminded of those old idioms: “if walls could talk,” “the walls have ears,” “to be a fly on the wall.” If these walls could talk, would they reveal the truth about what drove a woman named Emily Wright Harold to take a revolver from her son’s satchel, walk with purpose to a thicket on a chilly spring morning in 1872, and kill herself? And what’s the connection to former president Andrew Johnson? A mystery is born.

I love to dive through old newspapers. Often, while researching one story, another catches my eye. That’s how I came to this topic. As a matter of fact, newspaper articles provided the only information related to this matter. I searched Tennessee’s Supreme Court cases and Greene County court cases online. Nothing there. The same goes for Johnson’s biographies. Admittedly, I didn’t do exhaustive research. That kind of investigation entails traveling to Greene County and sifting through courthouse documents. Perhaps I’ll make that trip someday. For now, what I did find makes for a salacious anecdote in the former president’s life. Or . . . does it? I’ll present the information here and let the reader decide. I have a few theories of my own I’ll share as well.

Who was Emily Wright Harold?

Not much biographical information exists about Emily Wright Harold, save her name written in the census, and a sad little blurb on her Find-a-Grave page that reads “married 2 Nov 1837 Greene, TN.” According to the census, she was born in Tennessee. She married James W. Harold, who was appointed as Greeneville’s U.S. Postmaster in 1869. The 1870 census for Greeneville, Tennessee, indicates they had two children: Charles, thirteen, and Jessie, five. Newspapers in 1872 make no mention of the younger child.

The Harolds had been friends with the Johnsons for over thirty years. Their houses were “within a few steps of” each other.5)New York Herald. 1872. “The Greeneville, TN., Scandal: A Libel on Ex-President Johnson. How an Exemplary Lady was Driven to Commit Suicide.” The New York Herald, May 29.6)Knoxville Weekly Chronicle. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How It Started and It’s Terrible Results.” Knoxville Weekly Chronicle, May 29.7)Bristol News. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How it Started and its Terrible Results.” Bristol News, June 14. Emily was ostensibly Eliza Johnson’s close friend and confidante.8)Knoxville Weekly Chronicle. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How It Started and It’s Terrible Results.” Knoxville Weekly Chronicle, May 29. Townspeople described Emily, among other things, as “a pure, virtuous, Christian lady”9)New York Herald. 1872. “The Greeneville, TN., Scandal: A Libel on Ex-President Johnson. How an Exemplary Lady was Driven to Commit Suicide.” The New York Herald, May 29.10)Knoxville Weekly Chronicle. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How It Started and It’s Terrible Results.” Knoxville Weekly Chronicle, May 29.11)Bristol News. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How it Started and its Terrible Results.” Bristol News, June 14. and “a chaste and faithful wife.”12)Knoxville Weekly Chronicle. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How It Started and It’s Terrible Results.” Knoxville Weekly Chronicle, May 29. What was her involvement with Andrew Johnson?

Johnson had been in politics for almost forty years before he was impeached. He returned to his two-story home in Greeneville, where his old, prosperous tailor shop also sat adjacent to his library. His adjustment to “civilian” life was difficult. He seemed smothered by the lackluster, quiet life, writing to his daughter, Martha: “I long to be set free from this place forever I hope.”13)Havelin, Kate. 2005. Andrew Johnson. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications Company. p. 99 He “was desperate for some role in politics again” so he ran for Senate in 1869 and 1872, but lost both elections.14)Havelin, Kate. 2005. Andrew Johnson. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications Company. p. 99 Johnson was itching from the poison vine of boredom and Mrs. Emily Harold may have been the balm.

The Scandal

Emily apparently assisted the tailor in the former president’s old shop. She likely walked there several times, back and forth, passing Johnson’s adjacent library on the way.15)New York Herald. 1872. “The Greeneville, TN., Scandal: A Libel on Ex-President Johnson. How an Exemplary Lady was Driven to Commit Suicide.” The New York Herald, May 29.16)Knoxville Weekly Chronicle. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How It Started and It’s Terrible Results.” Knoxville Weekly Chronicle, May 29.17)Bristol News. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How it Started and its Terrible Results.” Bristol News, June 14. In that library, she and Johnson supposedly indulged in multiple steamy “improper intercourse” trysts. Emily’s husband seemingly suspected the affair. Newspapers write that Mr. Harold camped out one night and saw his wife leave the library, hiding herself “with a blanket shawl thrown over her head.”18)New York Herald. 1872. “The Greeneville, TN., Scandal: A Libel on Ex-President Johnson. How an Exemplary Lady was Driven to Commit Suicide.” The New York Herald, May 29.19)Knoxville Weekly Chronicle. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How It Started and It’s Terrible Results.” Knoxville Weekly Chronicle, May 29.20)Bristol News. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How it Started and its Terrible Results.” Bristol News, June 14. He stopped her, but she eluded him and ran toward the backdoor of their house, hoping she could enter the house and possibly feign she’d been home all along. Mr. Harold “anticipated her, went to the back door, and there found his suspicions confirmed.” Neighbors reportedly heard them argue loudly, using “high words.”21)New York Herald. 1872. “The Greeneville, TN., Scandal: A Libel on Ex-President Johnson. How an Exemplary Lady was Driven to Commit Suicide.” The New York Herald, May 29.22)Knoxville Weekly Chronicle. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How It Started and It’s Terrible Results.” Knoxville Weekly Chronicle, May 29.23)Bristol News. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How it Started and its Terrible Results.” Bristol News, June 14.

Mr. Harold went to work that April and found an anonymous letter waiting for him at the post office. The message detailed the “improper intimacy” between Emily and Johnson. The couple must have resolved the prior incident, because reports say Mr. Harold didn’t believe the letter’s accusations. He showed the letter to his wife and she absolutely lost it. She was livid and repeatedly denied the affair. That evening, she was like a mad woman, described as being “almost crazy with excitement.” She took a gun and threatened to shoot the slanderer. Rumors subsequently spread like wildfire in and outside of Greeneville, and the buzz could not be quelled. The couple’s son, a young army lieutenant, came home on leave and was kept none the wiser about the scandal. A few days after his arrival, Mrs. Harold received word her mother was gravely ill; so, she left, accompanied by her son, to “get away” and care for her mother.

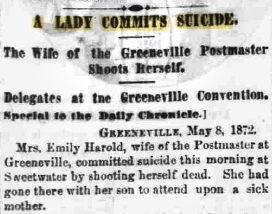

On May 8th, Emily woke up before sunrise and checked on her mother. She then rummaged through her son’s satchel, took his revolver, walked outside “some distance from the house,” and “shot herself through the left breast and through the heart.” Other accounts say she shot herself in the head.24)Nashville Union and American Saturday. 1872. “That Slanderous Report: Social Assassination.” Nashville Union and American Saturday, May 25. The strange thing is – and here’s where things become interesting – three shots were heard.25)New York Herald. 1872. “The Greeneville, TN., Scandal: A Libel on Ex-President Johnson. How an Exemplary Lady was Driven to Commit Suicide.” The New York Herald, May 29.26)Knoxville Weekly Chronicle. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How It Started and It’s Terrible Results.” Knoxville Weekly Chronicle, May 29.27)Bristol News. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How it Started and its Terrible Results.” Bristol News, June 14.28)Nashville Union and American Saturday. 1872. “That Slanderous Report: Social Assassination.” Nashville Union and American Saturday, May 25. Emily Wright Harold died from alleged self-inflicted injuries. She was 52 years old. The following headline and writeup in the Knoxville Daily Chronicle on May 9, 1872, reads:

Most Greeneville citizens believed she committed suicide because of the letter’s slanderous accusations. They ardently denounced the rumors and defended her character through letters to various newspaper editors. Further, citizens also stood up for Andrew Johnson. The former president did not seduce Mrs. Harold, they said; and the Greeneville community did not feel “great indignation” against the ex-president. For his part, the former president “declared the lady had never been in his library.”29)New York Herald. 1872. “The Greeneville, TN., Scandal: A Libel on Ex-President Johnson. How an Exemplary Lady was Driven to Commit Suicide.” The New York Herald, May 29.30)Knoxville Weekly Chronicle. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How It Started and It’s Terrible Results.” Knoxville Weekly Chronicle, May 29.31)Bristol News. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How it Started and its Terrible Results.” Bristol News, June 14. (Note the lack of denial there.)

The Letter-Writer

A few months later, the culprit who allegedly wrote the letter was identified as R. C. Harne (or Horn). He was arrested “on the charge of libel.”32)Knoxville Weekly Chronicle. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: The Case Being Investigated in Court.” Knoxville Weekly Chronicle, July 31. Harne’s handwriting supposedly matched the letter’s penmanship. At issue, however, was whether the letter’s charges were legitimate. Three witnesses – two African American men and one White man – swore the charges were true. Mysteriously, “they were arrested for perjury soon after” their testimony.33)Knoxville Weekly Chronicle. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: The Case Being Investigated in Court.” Knoxville Weekly Chronicle, July 31. After publishing details of the court’s examination, the Knoxville Weekly Chronicle was sent what amounts to a “cease and desist” letter from the defendant’s attorneys.34)Knoxville Weekly Chronicle. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: The Case Being Investigated in Court.” Knoxville Weekly Chronicle, July 31. After this injunction, the trail runs dry.

Two-Cent Theories

1.False Charges

What if the adulterous charges were untrue? Johnson was running for Congress – put his name in the hat twice and lost. Admittedly, he was a “disgraced” President, but some sneaky political maneuvers may have been at play. History provides us with an example. In 1845, Johnson ran for a U.S. Congressional seat against one Parson Brownlow. The campaigns were brutal and cut-throat. A plan was formed against Johnson:

If Johnson could not be defeated in open debate, he must be crushed by insinuation and by charges so foul none would vote for him . . . In the campaign of 1845, therefore, it was decided that Johnson must be destroyed.35)Winston, Robert W. 1928. Andrew Johnson: Plebian and Patriot. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 64

Perhaps political envoys employed similar tactics and concocted a liaison with Emily Harold to crush Johnson and ensure his ultimate defeat. His political career would be – and was – over.

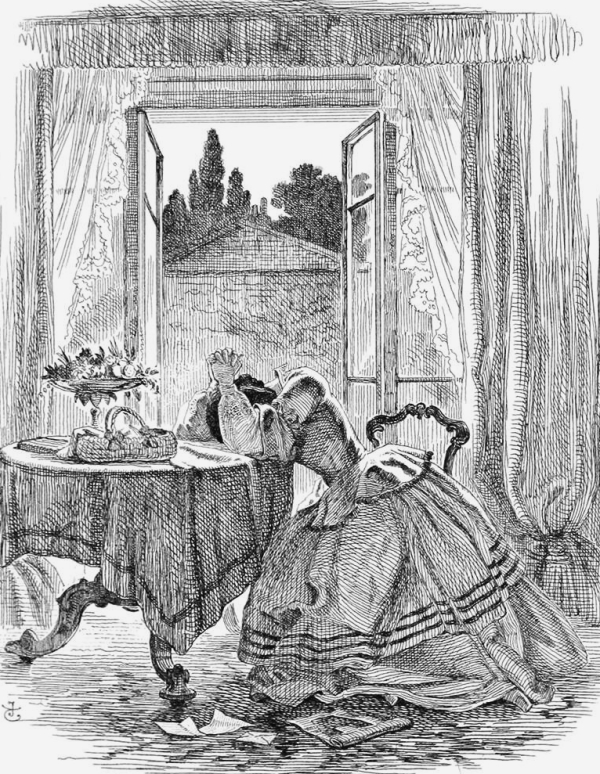

Victorian society, even in the States, was notoriously ostentatious and judgmental. A person was socially ruined with only a hint of scandal, even if untrue. If Emily was innocent, she may have committed suicide to avoid the social ostracization. One need only look toward the era’s literature. Tales abound about women who’ve fallen from society by a mere mention of one thing or another. For example, the stunningly beautiful Lily Bart in Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth, is innocent of wrongdoing, but is accused of having an affair with a married man in order to pay off debt. The man she loves also believes the rumor. By the end of the novel, Lily is destitute and addicted to a hypnotic sedative. She overdoses, and the reader is left wondering whether her death was intentional or accidental. Though the novel was published in 1905, the same narrative of the “fallen woman” is found in earlier literature.

2. True charges

What if the adulterous charges were true? An old adage says something like “not all rumors are true but some truths lie in all rumors.” Emily Harold’s actions are a bit, well, as Shakespeare puts it: “The lady doth protest too much, methinks.”36)Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 2 Her emotions are all over the place and she tries a little too hard to espouse her innocence, even going so far as to wave a gun around and threaten to shoot the letter writer. An affair is not far-fetched, either. Johnson was a prominent man, and, some may believe, politically successful. His wife was, for all intents and purposes, disabled and bedridden. He may very well have seduced Emily. The guilt of it all and the fear she would be “found out” may have led to her tragic end.

3. Murder?

What if Emily Harold was murdered? The three gunshots in the woods bother me. And, where exactly did she “shoot herself”? As already stated, newspaper reports say she “shot herself through the left breast and through the heart.” But even this is sketchy. The same articles conclude the following:

Three shots were heard, the alarm was given, and soon after she was found in a dying condition. It was supposed the first shot was fatal, as it set fire to her clothing which were burning when found. She was carried to the house but died before she reached it, never uttering a word. [emphasis added in sentence two]

Her burning clothes suggests a close-range shot, so, suicide is certainly possible. However, if a person shoots herself in the heart, how in the world can she shoot two more times? Let alone, in the head? Moreover, her son’s gun was a U.S. Army issued single action revolver, most likely a Colt. A single action revolver works by pulling back the hammer with the thumb and the other hand, then pulling the trigger to release the hammer. It would be extremely difficult for anyone – male or female – to fire the gun by simply pulling the trigger. Pulling back the hammer took some strength. One must manually cock the gun and pull the trigger and it must be done every time the weapon is fired. Take Spaghetti Westerns, for example. All those Clint Eastwood movies where he uses two hands – one to pull the trigger and the other to cock the hammer.

I know I’m going out on a conspiratorial limb here, but the possibility of Johnson’s political agents silencing Mrs. Harold is not implausible.

Or, if you’ll please indulge me on another conspiratorial front, maybe she was lured there under the pretense that someone – a certain someone who wrote the letter – wanted to talk. She’d finally have the opportunity to kill that person. Perhaps she fired the first shot and another person fired the latter two – one in her heart, one in her head.

Conclusion

So . . . What do you think? One can theorize all day long, but the fact remains that Emily Wright Harold died on May 8, 1872. She was a woman who may have felt trapped in her marriage or fell for Johnson’s lines or was truly altogether innocent of the affair. I’ll end with a quote from Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth:

I have tried hard – but life is difficult, and I am a very useless person. I can hardly be said to have an independent existence. I was just a screw or a cog in the great machine called life, and when I dropped out of it I found I was no use anywhere else.

** Featured Image “Hair” by Jules Leon Flandrin, late 1890s – Old Book Illustrations

References

| ↑1, ↑2, ↑3 | National Park Service. 2020, Updated. “Andrew Johnson’s Family.” National Park Service. July 4. |

|---|---|

| ↑4 | Havelin, Kate. 2005. Andrew Johnson. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications Company. p. 64 |

| ↑5, ↑9, ↑15, ↑18, ↑21, ↑25, ↑29 | New York Herald. 1872. “The Greeneville, TN., Scandal: A Libel on Ex-President Johnson. How an Exemplary Lady was Driven to Commit Suicide.” The New York Herald, May 29. |

| ↑6, ↑8, ↑10, ↑12, ↑16, ↑19, ↑22, ↑26, ↑30 | Knoxville Weekly Chronicle. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How It Started and It’s Terrible Results.” Knoxville Weekly Chronicle, May 29. |

| ↑7, ↑11, ↑17, ↑20, ↑23, ↑27, ↑31 | Bristol News. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: How it Started and its Terrible Results.” Bristol News, June 14. |

| ↑13, ↑14 | Havelin, Kate. 2005. Andrew Johnson. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications Company. p. 99 |

| ↑24, ↑28 | Nashville Union and American Saturday. 1872. “That Slanderous Report: Social Assassination.” Nashville Union and American Saturday, May 25. |

| ↑32, ↑33, ↑34 | Knoxville Weekly Chronicle. 1872. “The Johnson-Harold Scandal: The Case Being Investigated in Court.” Knoxville Weekly Chronicle, July 31. |

| ↑35 | Winston, Robert W. 1928. Andrew Johnson: Plebian and Patriot. New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 64 |

| ↑36 | Hamlet, Act 3, Scene 2 |