“Only one thing in my life has been constant: my interest in words.

I should say “devotion” to words – for it has been a devotion, rarely known,

I suspect, except among the more megalomaniacally linguistic lovers

who have always come to people by way of words rather than the reverse.”1)Mackin, Randy. 2011. George Scarbrough, Appalachian Poet. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 61

–George Scarbrough

Our own Edward Francisco wrote a piece in July 2020 called “Appalachia’s Sons: A Triptych of Talent,” praising three Appalachian writers: Jesse Stuart, James Still, and George Scarbrough. The latter of these three, George Scarbrough, is our focus today. Francisco writes of the author:

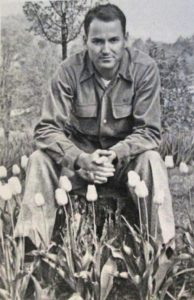

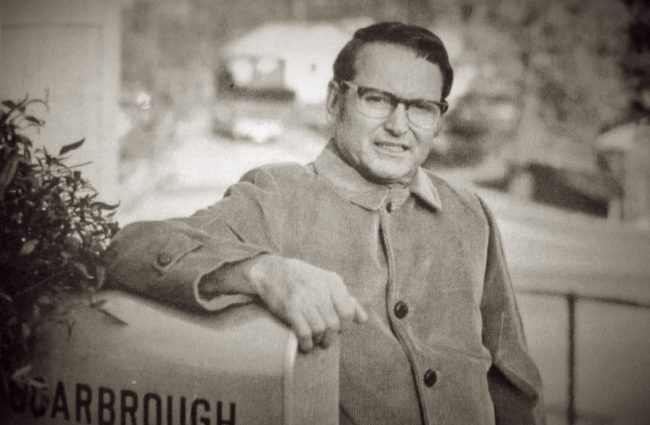

Born in Patty, Tennessee, in 1915, George Scarbrough lamented for much of his life the lack of critical attention his work received. Certainly, Scarbrough never garnered the recognition of the poets who endorsed his books, luminaries such as Allen Tate, Andrew Lytle, and James Dickey. One reason for his omission from this elite cadre was his failure to embrace modernism and its attendant free verse experiments. Scarbrough complained about being “self taught” early in his career, and it is accurate to say that he wrote almost exclusively in traditional forms. Only with the publication of Invitation to Kim in 1989, and its subsequent nomination for the Pulitzer Prize in 1990, do we witness a stylistic transformation characterized by innovation and eclecticism . . .

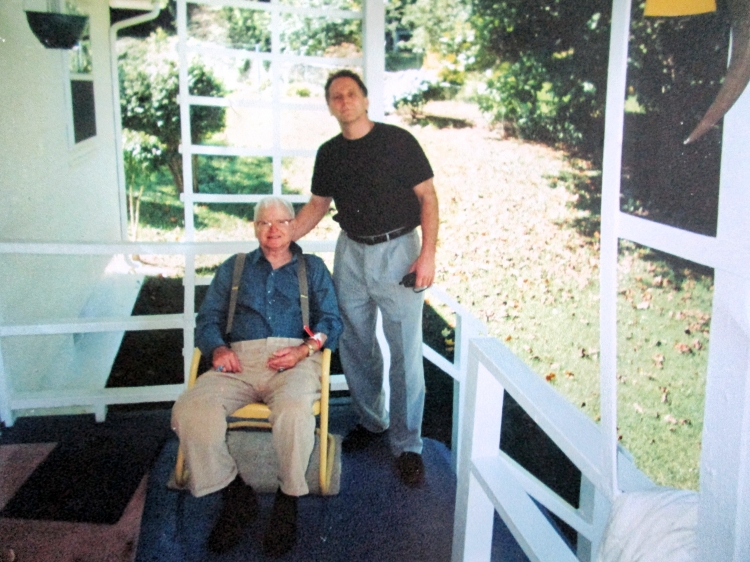

George was my friend for almost thirty years. He was a brilliant poet at his best but also a first-rate prankster. Those visiting him at his home at 100 Darwin Lane in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, will recall the rubber snakes he placed strategically around the yard and on the porch. He also never learned to drive, making him dependent on friends to take him to the grocery store and post office. “All the manuscripts I’ve sent out,” he complained, “and I’ve never so much as made my postage back.” As for being unable to drive, George dramatically recited Tennessee Williams’ Blanche Dubois: “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.”

In Spring 2000, The Iron Mountain Review honored the poet with his very own “George Scarbrough Issue,” where various poets and writers – Edward Francisco, Bill Brown, Randy Mackin, Connie Green – offered praises and critiques. His adoration for the Appalachian landscape is evident in his poetry. He loved the English language and word usage, and expressed what it’s like to be born and bred, blessed and bruised, in Appalachia. He understood and masterfully laid bare the engulfing concept of “what is.” He understood the nature he loved through his belief in Animism.2)Mackin, Randy. 2011. George Scarbrough, Appalachian Poet. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 111 Below are some comments from the essays:

In language combining the best of the formal and vernacular traditions, Scarbrough records the progress, in Flannery O’Connor’s memorable but borrowed phrase, “of several rough beasts slouching towards Bethlehem to be born.” His work rescues ordinary experience from the simulacrum of cliché by insisting on a fierce singularity in describing what we often fail to notice: our own status as ragged wayfarers hobbling toward a dream of home.3)The Iron Mountain Review, Volume XVI, p. 30

His topography is asplendor with the county landscapes and people of the Tennessee mountains and the small sharecropper cabins in which he spent his childhood . . . George Scarbrough, in his long productive life, has given and gives us still the “World of the lost heart on the edge of finding,” a mythos rich with wounds and healings, with language craft and music, with the mountain light and landscape which informs his poetry and enriches us all.4)The Iron Mountain Review, Volume XVI, p. 13

I also remember the first time I came to appreciate the poetry of George Scarbrough, because it was the same sensation delivered by the reading of Keats and Forché . . . And I remember thinking, here is a poet who is in love with the language.5)The Iron Mountain Review, Volume XVI, p. 14

Through reading and studying Scarbrough’s poetry, I have learned to recognize another man who “climb[s] the desperate mist,” the poet himself, transformed and transfigured through language, by love.6)The Iron Mountain Review, Volume XVI, p. 24

George Addison Scarbrough died on December 2, 2008. His final wish was found in his personal papers. He wanted his ashes scattered atop his parents’ grave and a brief epitaph “on a small brass plate” attached to their tombstone:

American Writer

George Addison Scarbrough

Son of Oscar and Belle

October 20, 1915 –

His mission was to teach the world to read.7)Mackin, Randy. 2011. George Scarbrough, Appalachian Poet. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 50

Please enjoy a few poems by George Scarbrough:

Old Trees8)The Iron Mountain Review, Volume XVI, p. 4

Crouch in the purple grass

Of the cratered field

In the low mountaintop.

Under the misplaced willow,

By the gnarled apple,

Something will cough your name,

A whistle will come. You

Will know how familiar:

Gate twisted on its hinge,

Chain drawn through an eye.

You can hear them opening

And closing as they move,

Calling you out:

Woodnotes that impinge

On that still passionate place:

Syllables of mossy silence,

Lobe and larynx

Of once lingual ground.

Friendship Cemetery in Summer9)The Iron Mountain Review, Volume XVI, p. 8

The wild rose, the blue pine,

The blackberry, the purple alum

Are the future of this place. They flourish

In a welter of liveliness, in scented silence.

To honor my father and my mother

I brought my wordbook here many times in the past

To test the strength of paradigm,

To chase verbs like rabbits.

Ah, those leaping verbs!

How they make the world go for the living

But are helpless here in an earth

Without grammar:

Where all sentences end

In the same parsing,

All verbs run down like clocks,

And real rabbits come

Nibbling mildly under the wild rose,

The blue pine, the blackberry, the purple alum –

All present and accounted for

In the wordless wind.

Scarbrough’s books of poetry can be purchased at Iris Press. Additionally, selections of his poetry and/or brief bios are on the following websites:

Appalachia Bare – “Appalachia’s Sons: A Triptych of Talent”

Appalachia Bare – “Lost and Found Poems: George Scarbrough”

Stay tuned . . .

Appalachia Bare will make an exciting announcement on Thursday!

**Featured Image from George Scarbrough, Appalachian Poet, by Randy Mackin

References

| ↑1 | Mackin, Randy. 2011. George Scarbrough, Appalachian Poet. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 61 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Mackin, Randy. 2011. George Scarbrough, Appalachian Poet. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 111 |

| ↑3 | The Iron Mountain Review, Volume XVI, p. 30 |

| ↑4 | The Iron Mountain Review, Volume XVI, p. 13 |

| ↑5 | The Iron Mountain Review, Volume XVI, p. 14 |

| ↑6 | The Iron Mountain Review, Volume XVI, p. 24 |

| ↑7 | Mackin, Randy. 2011. George Scarbrough, Appalachian Poet. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 50 |

| ↑8 | The Iron Mountain Review, Volume XVI, p. 4 |

| ↑9 | The Iron Mountain Review, Volume XVI, p. 8 |

George could, in fact, drive. He just didn’t like to. My university has his driver’s license from the early 2000s.