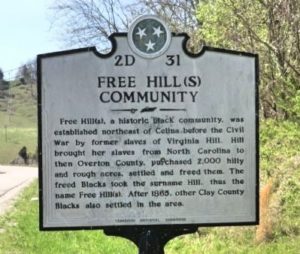

In the year 2000, my sons Erik and Gabriel and I set out to create a video documentary of the people living in Free Hills, one of America’s last remaining Black settlements established before the Civil War. Located in hardscrabble Clay County, Tennessee, near the community of Celina, the Free Hills have been home to freed slaves and their descendants for more than two centuries. Residents tell the story of Virginia Hill, daughter of a prosperous North Carolina planter, who inherited her father’s slaves, freed them, and bought property where they could live in relative safety and seclusion. Early accounts establish that the first slaves relocated in the rural wilderness were Virginia Hill’s biological children. If so, Hill may have been motivated to ensure her offspring’s safety as best she could. Too, she undoubtedly grasped the consequences of sexual relations between elite white women and enslaved men in the antebellum South, as historian Catherine Clinton explains:

White women whose affairs with slaves were made known faced varying degrees of public humiliation. When a planter’s daughter or wife was discovered to be pregnant by a slave, great pains were taken to cover up the pregnancy. The resulting child might have been sold into slavery, but infanticide was not an uncommon means of avoiding scandal.

Virginia Hill’s manumission of her slaves may have been inspired by the best of intentions, but life in Free Hills wasn’t easy from the outset. Tucked away in the Upper Cumberland region on the Tennessee-Kentucky border, Free Hills does not afford easy access, nor is farming viable, owing to geography marked by steep slopes and large outcroppings of rock. Trapping and fishing sustained early settlers who swept dirt floors and rode donkeys to accommodate the harsh terrain.

Despite difficulties, the community persisted, buoyed by the Free Hill Church of Christ, the historic heart of the community for two centuries, and the Free Hill Rosenwald School, built in 1929 with the aid of the Julius Rosenwald Fund,1)https://aliciapatterson.org/stories/saving-rosenwald-schools-preserving-african-american-history a grant program directed by Booker T. Washington. For a time it seemed that Free Hills thrived as it was home to approximately 400 people between 1920 and 1950. Free Hill’s Hill Top Café was a popular gathering spot for the locals. Juke joints sprang up where people came to drink beer and play blues music – with names like Bud’s Snack Bar, the Blind Pig, and the Tip-Toe Inn. However, the community’s ascendancy was short-lived.

When my sons and I visited Free Hills on the cusp of a new millennium in 2000, signs of dissolution were very much in evidence. The population had shrunk to almost 200. Once vibrant businesses had closed. The one-two punch came when the local garment industry relocated to Mexico and a home health firm closed its doors, shuttered its windows, and moved just outside Nashville. Unemployment in Free Hills soared. As an elder of the community explained to me:

“There’s nothing for young people here. They’ll likely leave and never come back. Who can blame them?”

For the young people who stayed, the prospects were grim. It was no coincidence that most of the people I interviewed were older. My son Erik, at that time a social worker advocating for the elderly poor, had arranged for me to record conversations with some of his clients. The young folks he’d approached all balked. The reasons became increasingly clear when I quizzed their elders about the greatest threat to Free Hills. It wasn’t the economy. It wasn’t the occasional terrors inflicted by the Ku Klux Klan.

“Drugs” was the unanimous reply of everyone I interviewed. All agreed that crack cocaine was the scourge driving Free Hills toward extinction. (I’d read earlier that the National Trust had placed the Rosenwald School of Clay County, Tennessee, on its list of Most Endangered Historic Places.)

As strangers, we had no way of knowing the severity of the problem. Yet, we were about to glimpse – literally – a transaction taking place under our noses. While we were interviewing his grandparents, the couple’s teenaged grandson traded an envelope for a fistful of cash handed him by a white teen. The living room window afforded my son Gabriel, our videographer, an opportunity to record the drug deal in real time.

While our visit to Free Hills was emotionally draining, we had the option of leaving. In fact, it was inconceivable that anyone would stay given a chance to leave. There was just too much of what author James Agee termed the “cruel radiance of what is” in the faces of the people we met. Grinding poverty, frustrated potential, and institutional racism had leeched the life blood of Free Hills residents. Was it any wonder the young people turned to drugs? Without legal opportunities to secure a livelihood, they opted for illegal means, in addition to anaesthetizing themselves from the shards of the fractured American dream.

From several hundred miles away, I tracked the status of Free Hills to the extent I could. In the early 2000s, I read that the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) had conducted a sting operation in the Celina-Free Hills area for possession of controlled substances. Around that time, someone directed me to a Detroit based rap group who referenced Celina in their lyrics as a key location on the I-75 “drug corridor.”

In 2016, Joey Garrison, a reporter for the Nashville Tennessean, wrote an article about the state of Free Hills. He reported that only 70 or so residents still called the community home. One of the remaining few, 62-year-old Ollie Page, described it this way: “It scares me that one day it’s going to be a ghost town.” Page could have been sounding the death knell for one of the country’s last remaining Black settlements populated by freed slaves.

On the ride from Free Hills down to Celina, I mused aloud, wondering what Abraham Lincoln would have thought of a unique, once vital, African-American community established two decades before the 16th president signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

Steering the car around serpentine curves, my son Erik spoke up:

“His grandparents are buried about a mile from here.”

“Whose?” I asked.

“Lincoln’s.”

“Are you sure?”

I’d read Carl Sandburg’s Lincoln and later, Gore Vidal’s interpretive biography, but I didn’t recall that Lincoln had family connections in Tennessee.

Erik eased onto the shoulder and made a U-turn, pointing the car in the opposite direction on state route 53. In a few minutes, we pulled off, parking and exiting the car just yards from a Tennessee Historical Marker alleging that Lincoln’s paternal grandfather, Hannaniah, and the president’s grandmother were buried on private property near Tinsley Bottom in Clay County. Erik knew the land’s owner who granted us permission to explore the cemetery overgrown and choked with weeds. We found Hannaniah’s grave marker affixed by the Tennessee State Historical Commission (THC).

“I don’t think it’s accurate, Erik,” I said.

I knew that Lincoln was wreathed in folklore, making people eager to place him in locations that he never visited or stick him on a limb in someone’s family tree. I suspected that was the case here. The next day I visited the Celina Public Library. After a couple of hours, I found what I was looking for: an article written by an historian in 1912 discounting the possibility that Lincoln’s grandparents were buried in Clay County. The historian’s genealogical research revealed that Hannaniah Lincoln was actually the president’s second half cousin. Obviously, I wasn’t the first person to discover the error. I wondered whether the Tennessee Historical Commission knew of the mistake. The presence of the marker suggested they didn’t.

The next afternoon I picked up the phone. The woman at THC was pleasant at first before discovering the reason for my call.

“Do you know how much those markers cost?”

“No.”

“A thousand dollars each!”

I suggested in the interests of accuracy that the Commission take down the marker, bite the bullet, and erect a new one. During the rest of our conversation, the woman urged me, for all intents and purposes, to mind my own business. The marker wasn’t coming down.

It was my initial immersion into the post-truth world where notions of “truth,” “fact,” and “reality” are malleable and not subject to usual standards of proof and verification. In fact, such slippery notions are merely “constructs” waiting to be “deconstructed.” Did it matter whether the inhabitants of Free Hills died off? If that happened, did they ever really exist? When truth proves inconvenient, why not substitute a more convenient “reality” conducive to amnesia and not fettered by facts?

That seems to be the impulse of Governor Bill Lee and Republicans in the Tennessee legislature who recently passed a bill banning the teaching of critical race theory in public schools at a time when such an initiative is needed most. Avowedly, the GOP-controlled General Assembly now prohibits educators from “teaching things that inherently divide people.” The lawmakers’ ahistorical approach to problems still plaguing the body politic is an attempt to absolve themselves and their ilk of sins associated with racism. Their ritual magic insists that history conform to fantasy. The prescription for weaponizing lies and annihilating truth requires a series of insidious steps: Obscure the lens of reality, deny plausibility, and insist that a significant minority of the population invalidate their own experience, becoming invisible, in effect.

The Free Hills, in contrast, offer a stark testimony to the truth of America’s tensions, contradictions, and disappointments clouding the vision of the Founders, of whom Virginia Hill was surely one. As for poor, beleaguered Abe Lincoln, he posed a question at Gettysburg before which we should all still tremble:

“Can a nation so conceived, and so dedicated, long endure?”

To Lincoln’s disquieting query, the fate of Free Hills may ultimately supply the answer.

**Featured Image captured from “History of Free Hill Tennessee” on YouTube by MrTumbles08

Check out the following videos about Free Hill(s):

Free Hills Community WCTE PBS

History of Free Hill Tennessee (picture gallery)

References

| ↑1 | https://aliciapatterson.org/stories/saving-rosenwald-schools-preserving-african-american-history |

|---|

![Abraham Lincoln's grandfather, Abraham [Linkhorn] Lincoln - tombstone_Fotor425 scenes cloudy](https://wp-modula.b-cdn.net/spai/q_glossy,ret_img,w_425,h_306/https://www.appalachiabare.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Abraham-Lincolns-grandfather-Abraham-Linkhorn-Lincoln-tombstone_Fotor425-scenes-cloudy.jpg)