“Shut up, you fucker. You smart-ass. If I wasn’t crippled, I’d get up right now and smack your head and ass together.”

– Mamaw from J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy

My suspicion is that J.D. Vance tries to shock his readers by pretending he’s unfazed by his family’s white trash doings. For Vance, it’s all de riguer – Mamaw’s obscenities, Mom’s whoring and alcohol fueled violence, Papaw’s churlishness and unexplained disappearances. The message of Hillbilly Elegy? Vance loved them anyway – rogues, scoundrels, sociopaths – one and all. Not only that, but the author is able to penetrate the surface of appearances, discovering the inherent good in his people: “Mom was the smartest person I knew” and “He [Papaw] taught me that lack of knowledge and lack of intelligence aren’t the same.” What to make of these contradictions that don’t seem the least disturbing to Vance? Then there are cracks in his narrative where pieces of the story appear not to fit.

For example, the locations where the narrator claims to have spent his childhood shift underfoot without warning. It is understandable that his family moved from Kentucky to Ohio in an effort to escape grinding poverty. It’s also credible that Vance’s mother and third husband, Bob, squandered a hundred thousand dollars a year of combined income. Never having had money, they didn’t know what to do when their fortunes reversed. However, Vance seems to exaggerate his hardscrabble circumstances and the violence to which he was exposed as a result of his hillbilly origins. At one point in the book, he admits that, although his mom and Bob had blow-ups over money, “Bob never was abusive.” Nor was young Vance’s experience unique or even much a departure from the norm in his Middletown, Ohio, community:

(p. 73)

Mom and Bob weren’t that abnormal. It would be tough to chronicle all the outbursts and screaming matches I witnessed that had nothing to do with my family. My neighbor friend and I would play in his backyard until we heard screaming from his parents, and then we’d run into the alley and hide. Papaw’s neighbors would yell so loudly that we could hear it from inside his house, and it was so common that he’d always say, “Goddammit, there they go again.” I once saw a young couple’s argument at the local Chinese buffet escalate into a symphony of curse words and insults. Mamaw and I used to open the windows on one side of her house so we could hear the substance of the explosive fights between her neighbor Pattie and Pattie’s boyfriend. Seeing people insult, scream, and sometimes physically fight was just a part of our life. After a while, you didn’t even notice it.

The author would have us believe that these behaviors are residual effects of hillbillies transporting their legacy of “irritability, aggression, and anger” to a new locale only to face social circumstances they were ill-equipped to handle. A simpler explanation may be that violence attends poverty not unique to hillbillies. Otherwise, how did Vance manage to escape, and from what exactly is he escaping? There’s certainly none of the physical or psychic scarring of Dorothy Allison who shows the lingering manifestations of trauma:

(pp. 32-33)

Let me tell you about what I have never been allowed to be. Beautiful and female. Sexed and sexual. I was born trash in a land where the people all believe themselves natural aristocrats. Ask any white Southerner. They’ll take you back two generations, say, “Yeah, we had a plantation.” The hell we did.

I have no memories that can be bent so easily. I know where I come from, and it is not that part of the world. My family has a history of death and murder, grief and denial, rage and ugliness – the women of my family most of all.

The women of my family were measured, manlike, sexless, bearers of babies, burdens, and contempt. My family? The women of my family? We are the ones in all those photos taken at mining disasters, floods, fires. We are the ones in the background with our mouths open, in print dresses or drawstring pants and collarless smocks, ugly and old and exhausted. Solid, stolid, wide-hipped baby machines. We were all wide-hipped and predestined. Wide-faced meant stupid. Wide hands marked workhorses with dull hair and tired eyes, thumbing through magazines full of women so different from us they could have been another species.

Vance never wants his readers to forget that, despite being “disadvantaged,” he attended Ohio State University and Yale Law School. In fact, his purported reason for writing Hillbilly Elegy was to answer two questions disturbing him since his first days as a student in law school: “Why does this elite institution seem so culturally foreign? And, relatedly, why are so few kids who grow up the way I did make it to our society’s elite institutions?” Unfortunately, Vance fails to answer either question. But he does give us clues to his thinking.

Ever popular among self-styled conservatives, like Vance, is the notion of “grit” – the resilience enabling an individual to achieve extraordinary feats through perseverance and passion. An enthusiast writing about grit, Angela Duckworth, argues that “grit can be learned, regardless of IQ or circumstances.” Vance falls right in line with Duckworth’s thinking. He admits to finding plenty of support from his “intellectual fellow travelers in the Republican party” who support Vance’s political domestic agenda:

(p. 261)

We can easily create a welfare state that accepts the fact of a permanent American underclass, one where family dysfunction, childhood trauma, cultural segregation, and hopelessness coexist with some basic measure of subsistence. Or we can do something considerably more difficult: reject the notion of a permanent American underclass.

Whether he intends to or not, the writer is situated in cultural privilege enough to insist on having it both ways: being a part of the tribe while being apart from the tribe and conveniently choosing when to be which. Vance tells us that he “never felt like a foreigner in Middletown.” Yet, he’s comfortable chumming with Charles Murray, co-author of The Bell Curve, the controversial 1994 book arguing that a cognitive elite drives society, while ethnic-racial groups with lower IQs drain resources, contributing to stagnation. Like Vance, Murray recommended the elimination of welfare policies that encourage poor women to have babies:

The technically precise description of America’s fertility policy is that it subsidizes births among poor women, who are also disproportionately at the low end of the intelligence distribution. We urge generally that these policies, represented by the extensive network of cash and services for low-income women who have babies, be ended. The government should stop subsidizing births to anyone rich or poor. The other generic recommendation, as close to harmless as any government program we can imagine, is to make it easy for women to make good on their prior decision not to get pregnant by making available birth control mechanisms that are increasingly flexible, foolproof, inexpensive, and safe.

When all is said, I can only respond with a fair amount of cynicism, suspecting that J.W. Vance’s encomium to his upbringing is a ruse, of sorts – window dressing for a more sinister purpose. Though I never knew her, except in Vance’s words, I can almost hear his mamaw’s stern warning echoing in my ears: “J.D., a hillbilly with a little education is a dangerous thing.”

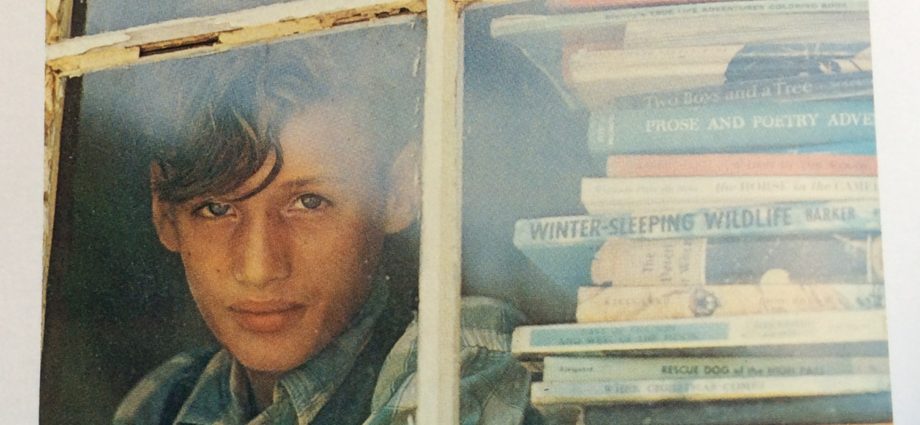

**Photo Source: American Mountain People, National Geographic Society 1973/ Photographer Bruce Dale

This is an absolutely devastating take down.

I’d be interested in hearing your take — as a scholar of literature — on this book as an “elegy.” What, if anything, is being elegized? If Vance is chronicling an escape from a dysfunctional hillbillydom — which as you say seems to be the core of the book — wherein lies the elegy?

Jud: When I think of an elegy, a panegyric, Thomas Gray’s “Elegy in a Country Churchyard” comes to mind. Inspired by the passing of a fellow poet, the poem ends with a meditation on death and loss. It’s a paean to the anonymous rustics buried in the graveyard. To my thinking, your question “What, if anything, is being elegized?” is spot-on. For the life of me, I can’t figure it out. Vance isn’t mourning a way of life. He doesn’t grieve the deaths of specific individuals. I suspect it’s an example of Vance’s language intended to disguise his true agenda. (Vance boasts of his talents as a writer suggesting the illusory superiority of someone manifesting the Dunning-Kruger effect.) It’s not by accident that he sings the praises of eugenicist Charles Murray whose solution to the “problem” of disproportionately unintelligent African Americans and their poor rural white counterparts is sterilization. If such a public policy came to pass, Vance might actually have something to grieve about, but what would Trump do for a “base”?

Have you read “Appalachian Reckoning”?

The popular perception is that memories are stored in a specific areas of the brain, like RAM in a computer, and recalled intact. In truth, memories are reconstructed from various neural networks through out the brain and are not apart from the emotions and political leanings of the person doing the recalling. So, I take Vance’s story for what it is: just as authentic as any other Appalachian story but told from the viewpoint of a Republican conservative. I can appreciate his experience and his accomplishments, despite the odds, without buying into the straw men he builds with them. You nailed his flawed inductive logic with this sentence: “A simpler explanation may be that violence attends poverty not unique to hillbillies.” While you aptly honed in on the murky parts of his story, and the prospect of a political agenda, there is clearly a message floating in the red tide that spread across southern Appalachia in 2016.

Jimmy, thank you for your fine and nuanced insights and for your support of our blog. There’s no denying that “red flood,” and given the pathetic showing of the Democrats, it won’t surprise me if Trump’s base gives him a second term. The Dems appear to have learned nothing in the wake of the unsettling loss of 2016. Bill Clinton allegedly told Hillary’s campaigners that “you can’t ignore Appalachia and the Rust Belt.” The Wellesley girls said that Bill was old-fashioned and out of step with the times. Bernie Sanders is the Ralph Nader of the current Democratic Party. Sad spectacle all around.

Man, this text is a rollercoaster of emotions! Vance’s story is so raw and real, it’s like a punch in the gut. The contradictions and cracks in his narrative keep me on my toes. Can’t wait to read more about his journey!