In the primeval forests of Appalachia, among the wildness, among the coal mines and their homegrown communities, waters flow. From mountain ridges these waters course and trickle into one another. Momentum from this continuum carves, molds, and sculpts ancient rock. Ever so slowly, water erodes away the lithology. Soluble minerals in mountain rocks – such as calcite and gypsum – dissolve. Feldspar and other silicate minerals weather down to clay. Iron bearing minerals, such as pyroxene, amphibole, and biotite oxidize and turn sediment to a characteristic red mud. As the mountains change, the babbles of small streams collide, sing, and join the chorus of a larger river system. Across a lush, damp, lonely woodland, fish and insects, coyotes and bears, all creatures who wander such an elemental creation, drink from these waters.

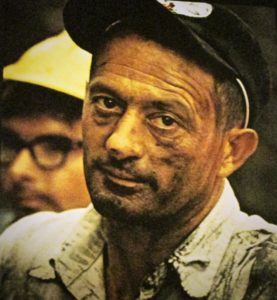

A West Virginia coal miner listens to a nearby creek washing over old mountain stones. He sharpens his pickaxe, settles his headlamp on a worn, battered, and stained helmet. In his lunch bucket, he carries West Virginia’s famous pepperoni rolls and a Tennessee Moon Pie – satisfying food for the underground. On his way to the miners’ car, he listens to the water’s ovation. He stops, looks to the nearby creek, and saunters over – his head filled with weary thoughts of the day ahead. Breathing deep the lucid air, he stares at the stream’s bank and scratches his chin. A fern grows.

On March’s infant spring morning, among the faint blue and billowy gray cool mist, the fern frond rises. Barely awake from winter’s slumber, the pinnate, waking featherlike leaf is curled and fiddled – unraveling for a chance at the sun. In a few short weeks the fiddlehead will mature, stand, and shade the Appalachian floor. Outstretched, as water and sugars travel through the plant’s tissue, tiny spores will form the genetic base for the next life-cycle of the fern. Clustered together on the leaf underbelly, the spores will grow, divide and mature. Soon enough they will drop to the forest floor for their chance to grow the next generation.

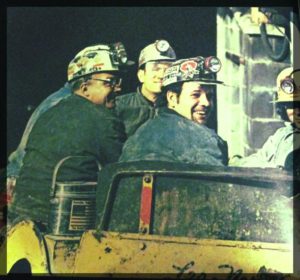

The miner’s coal-creased face brightens with happiness about the coming spring. A breeze picks up; a fresh, isolated mist promises a rejuvenating pour. Right on time, a whistle shrieks from the nearby coal mine. Best leave for the old coal shaft and let the fern alone. He says hello to fellow laborers – brothers and friends. With smiles and jokes around, a little bit of anxiety comes over him as he sits in the mining cart. Into the darkness they go. The rock around him is old and tells an incredible story – a tale of ancient processes, of a world crafted by the wisdom of a timeless terrain.

Simply imagine, a time existed long ago when no plants grew and the earth was bare. In fact, plants did not even exist. Beyond that, the land sustained no life at all. Though life thrived in the oceans, in the time of the early Paleozoic Era, the terrestrial realm was barren – a lifeless gray and brown. When thunder rolled and lightning crashed, torrents poured on an uninhabited landscape. Flash floods raged across the desolate view. In the shallow marine waters, however, algae and fungal slime molds, were adapting and responding to the environment as they evolved.

Living organisms came to land. Fungi and algae adapted to life outside the marine realm. Then lichens – a mutual, co-evolutionary relationship among the algae and fungi – found a home with one another on bare rock. These forms secreted acid into the environment, breaking down rock and dissolving minerals to feed. Their acid would break, mold, and crack the lithology. Water then entered the etched crevices. Biotic life formed Earth’s primitive soil. Eventually, a speckle of green was able to occupy the dampened periphery of land – the first plants had evolved from algal ancestors. They lived in that desolate world, with an isolated view, but their significance is profound.

The first plants were simple – they had no true root systems, no true leaves, no seeds, but carpeted the land. These plants were bryophytes – ancestral forms of today’s moss. They clung to the soil with small rhizoid fibers and reproduced with the production of alternating forms, from generations of spores to gamete producers to spores again. Once more, life adapted and evolved the genetic combinations necessary for survival. As fungi and lichen spread deeper into a damp landscape, the ancestral mosses followed. Their subtle adaptations over the epochs gave rise to a new complexity of forms and started a global revolution.

After this early Paleozoic Era came the Middle Paleozoic. Plants with true roots and leaves, true tissues to transport water, minerals, nutrients, and the strength to stretch toward the sun, evolved. The plants were still seedless, but, with the advent of true tissues, they grew heartily. New life abounded on the old Earth. The new plant tissues were so strong they changed Earth’s surface. Root systems dug into the ground, clinging to soil and regolith. When the rains came, for the first time in planetary history, roots held soil and rock in place. Water followed the path of least resistance – the planet’s river systems and watersheds formed. The rivers and their tributaries sculpted new landscapes. This allowed plants to travel further onto land and the animals followed.

Plants grew taller, developed wood, and a new way to reproduce. Fern trees spread across the land. Forests grew among the planetary creeks, brooks, streams, and larger rivers. As forest-hood advanced in succession, the first seeds evolved – a complexity in plant form that, for the first time, allowed plants to reproduce without the necessity of water. These new plants are the first appearance of gymnosperms. Their pollen and seed cones allowed these early ancestors of conifers, cyads, and gingko to spread deep into the uncharted territories of the terrestrial realm. Magnificent forests grew. These forests provided new habitat, new foods, and a new opportunity to pioneer life in the world.

Tiktaalik, an ancient fish with scales, gills, lobed fins, and the flattened head of a crocodile, would crawl onto land, stumble in a new world, then return back to the water. Transition species, animals from water to land, began exploring a new way of life. The mighty forests not only shaded the new animals from the sun, but their very transpiration – the shedding of water from their leaves – provided a cool space of relief. Soon enough, geologically speaking, animals, amphibian and reptile-like creatures, would reproduce in the hearts of these grand forests. The advent of the egg liberated animal reproduction from the water.

As life modified and changed the planetary system, deep forces within the Earth would change the world forever. Earth’s moving crust cracked and fractured into plates. Forests expanded with the closing of the ancient sea of Iapetus and new plant and animal life evolved. The continents of the world, in a grand, large-scale motion of the lithosphere, collided. The fractured earth crust, tectonically convecting across the mantle, had global ramifications. As the ancient Iapetus vanished, new volcanic activity, new mountains – the power of the internal Earth – changed the land. Even more, as the continents began their collision, an incredible new mountain system would rise. In the late Paleozoic Era, with the formation of Pangea, the Appalachian Mountains were born. The young mountain range ascended to the status of titans.

The ancient Appalachian Mountains were grand – more so than a Himalayan scaled mountain chain. As they grew, the land erupted, buckled, folded, faulted, and morphed. The ancient sea floor was uplifted, thrust onto continental rock. As faults and fold developed, Earth’s sediments and organic matter were compacted so, life was buried. The great-undisturbed pioneering forests were compacted and compressed. As epochs rolled on, this biotic material was altered; the organic matter, with increasing pressure, compressed to carbon, thus forming bands of coal. Ancient photosynthetic energy was stored as beds of sedimentary and metamorphic rock.

A long time has passed since the Appalachian Mountains first emerged. The humbled terrain was weathered and eroded over the past hundreds of millions of years. The mountains are humble, wise elders on an Earth of constant change. Still, the land and living world are entwined, both changing into one another. Coal is now a viable economic resource that fuels and imperils human civilization.

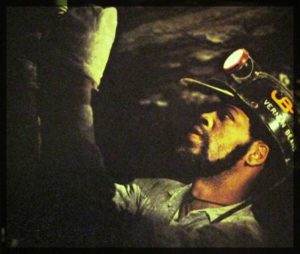

The miner’s longwall hits a seam of coal but he stops abruptly. He takes his pickaxe and hews the rock. The light strapped to his helmet catches something peculiar . . . He smiles to himself. The white imprint resembles the fern he observed hours earlier in the cool spring morning. He walks to the hallway deep in the mountain where his fellow miners are opening their lunch buckets and sits to eat. He pulls out his pepperoni roll with soot-covered hands, contemplates the fossil and the work that still needs to be done, but he is happy nonetheless. Today, he decorates his lunch with these flowers of darkness.

*Grant A. Mincy is an assistant professor of biology and (sometimes) geology at Pellissippi State Community College in Knoxville, Tennessee. He also sits on the Earth and Planetary Sciences Advisory Council for the University of Tennessee. In his free time, you’ll catch him either reading comic books or wandering around the Appalachian mountains with his wife and young son. Feel free to contact Grant (gamincy@pstcc.edu) or follow him on Twitter (@gmincy).

Very creative juxtaposition of the miner’s human story against the mind-stretching geologic time and powerful forces that have shaped the earth where he digs – art and science in one piece! I was intrigued to learn in Peter Brannen’s The Ends of the World that the weathering of the Appalachian Mountains might have been “responsible for a precipitous drawdown in carbon dioxide and the brief ice age that nearly wiped clean the evolutionary slate 445 million years ago” (end-Ordovician mass extinction)?

Hi Jim! Glad you liked the piece. The weathering Appalachians at the end Ordovician, and again in the Devonian, caused two large scale climate change events that kicked of mass extinctions. I’ve not read that book, will have to put Brannen on my list.

So timely. Thank you. Have you read this one yet?

https://www.newyorker.com/news/dispatch/the-battle-for-a-paycheck-in-kentucky-coal-country