Appalachia Bare would like to thank all our military and service members. This Memorial Day, we remember and honor all those who served and fought for our country. Our warriors in valor, strength, and excellence . . . The following is the fourth excerpt of Benny F. Shown Sr.’s memoirs about his time in Vietnam – and how it impacted his life.

The stewardesses placed pillows behind our heads and even set our feet on cushions. We were getting the red-carpet treatment. Then there came a girl pushing a tray-like table filled with ice and drinks – any kind you asked for, it was there. But there wasn’t no Tennessee Moonshine. A sergeant sat next to me. The stewardess asked him what kind of drink he wanted and he said,

“Scotch whisky.” I was asked next. I said,

“The same, please.”

I’d never tasted scotch before. But I did then and it was awful. By the time we got to McCord Air Base in Seattle, Washington, though, I felt pretty good. I got off the plane and thanked God I was home. But home was still quite a ways down the road. We were taken to a place and given showers, shaves, and new clothes. Our old clothes were burned. It was all happening too fast, but not fast enough, if that makes any sense.

We all went through this line and were seen by the medical department. After that, we were given money, tickets home, and then sent to a big mess hall for a dinner of anything in the world we wanted. I’d been craving a hamburger, a glass of milk, and a milkshake with French fries. I hadn’t seen any of this for a year and there it was. I ate like a pig. Then we were taken to Tacoma Airport. I still felt effects from that scotch when I stepped up to the ticket counter and was asked by a gentleman in a suit,

“Where to, soldier?”

“Give me a ticket to LaFollette, Tennessee,” I said.

He fanned through a big book, then stopped and said,

“I’m sorry, sir. There’s no airport in LaFollette, Tennessee. I can get you to Knoxville.”

I said that would be fine. He made all the stamps and printed the tickets, and told me about my flight – which one, time, and place. I had to wait an hour and thirty minutes. We were told not to tell anybody where we had been, not to mention Vietnam to any civilians because of protesters and trouble. They said not to wear our medals or ribbons, either – just civilian clothes. But I was so proud of my uniform that I’d had to have been beaten to death in order not to wear it. So, there I was waiting in the airport, in full uniform. My skin was tan and I’d been used to the hot climate over in ‘Nam, with temperatures hovering between 110-to-120-degrees. But I was now in below zero weather and thought I’d freeze to death. As I sat there waiting, a guy with long hair and peace signs on his clothes, carrying a guitar on his shoulder and leading a skimpily dressed girl, sat down across from me. I didn’t look at them because I didn’t want any trouble. I just wanted to go home. But . . . then it started.

“Hey, baby killer,” he said.

I never looked up. Then the girl started,

“Yeah. He’s a baby killer. You guys like killing babies.”

Then, she spat at me.

I didn’t say a word. I got up, turned, and went to the bathroom, just to keep out of trouble. I turned on the tap and splashed my face with water. The next thing I knew, there he was just standing there looking at me. I looked into his eyes with the piercing stare of a wolf cornered with no escape. I thought if I had to fight this man (if you could call him that); he would breathe his last breath. I spoke to him briefly in words I dare not say. I reckon I must have tapped into his weakness because he left, got his girlfriend, and was out of sight.

Finally, I boarded my flight and was on my way to Chicago, where I had a layover for the next flight to Knoxville. Once I was in Chicago, I couldn’t wait anymore. I went to the phone, called home, and my mother answered. She was quiet-spoken.

“Hello,” she said.

“Mom, I’m home. It’s Benny.”

Mom’s voice was full of joy. She hollered for my father, Hope Franklin, frantically calling out his nickname, “H.F.”:

“H.F! H.F! It’s Benny!”

Then, my dad took the phone. My ears were flooded with squeals, hollering, and crying in the background. I asked Dad if he’d be at the airport to pick me up. He said,

“Yes sir, son.”

I told him when to expect the plane and we said our goodbyes. I reached into my wallet and took out my fiancé’s picture – just for a little bit. (Twenty-eight years later, I’d have that same picture in my wallet.) She was seventeen years old. Though we went to separate schools, both of us had known each other for some time. Lord, she was ever so pretty (and she still is). I hoped she still loved me because I loved her more than life itself. A year is a long time to ask a pretty girl to wait for a broken boy.

When that Boeing 707 set down in Knoxville, I went numb. The plane stopped and we exited. A man – I don’t know who he was – passed by me and I got up behind him. He was a total stranger, a Black man in his late 50s or 60s with gray hair. He turned, held out his hand to shake mine, then said, “Oh, what the hell!” and he hugged me. I never saw him again.

We were off the plane and the soldiers were there. When I left, I looked back at them and they had turned their backs to me. I reckon there’s an old saying if you watch a soldier out of sight, you’ll never see him again. I turned to find my family standing there, reaching out to me with outstretched arms. Tears of joy and hugs and kisses abounded. And there was my fiancé. We kissed, and it was like a portion of Heaven. My family’s love was the food of life I’d been craving for a year.

When I got home, Mommy had the dinner table spread full of food. I just stood there and wept for a long time. There were actual spoons, forks, and knives, and even glasses and napkins! I’m sorry, but I ate like a wild animal. It’s amazing how tortured and animalistic a human can become during war. You find that you exist on instincts, not brains like a human being. As I ate Mommy’s cooking, I thought about those I left behind and how they must be eating; and it hurt so bad. The pain would never leave me. Ever.

After supper, we sat down and the evening sun was closing another page of time. I couldn’t rest. I started looking around frantically. My eyes darted everywhere. Where was it? I asked myself. I was looking for my M-16. My mind still over there. But I’m here, I thought, confused. Then I saw I was home and breathed a sigh of relief. And I wondered how long it would be that I’d stop being there. If only I’d known then that it would be forever. That I’d never stop being there. I’d probably have ended it all, but, being the reasonable person Mom and Dad brought me up to be, and loving God and fearing hell, I knew better.

I had a friend here. His name was Dennis. He wrote me a few times. Before the war, his house was like a second home to me, because I was always over there. He lived at home with his mom, dad, and sister. His father was a sheet metal worker. I just had to see them, so the next day, I went to Dennis’s house. Well, we all had a homecoming and Dennis and I planned a hunting trip to Walnut Mountain. When he and I were kids – sixth, seventh, and eighth grades – we squirrel hunted. But, this hunt would be my last squirrel hunt for a long time.

We went into the woods before daylight. It was cold and the sun was about 30 minutes from rising. As daylight broke, I heard shots – Boommm! Boom! And there it was. The chill in the air seemed to turn warm, and I heard in my mind, “G.I. You die tonight.”

To read other excerpts of Benny’s “Flashback in Time” series, see: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

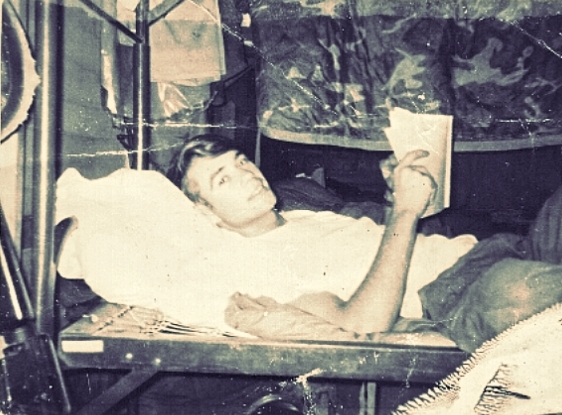

**Featured image of Benny F. Shown Sr. in Vietnam. Delonda’s father told her he often sent photographs home that portrayed his time in Vietnam in a different light so his family wouldn’t worry. This photograph shows him casually laying down and reading a book. In truth, the situation was more dire.