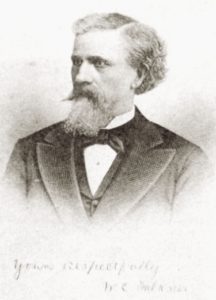

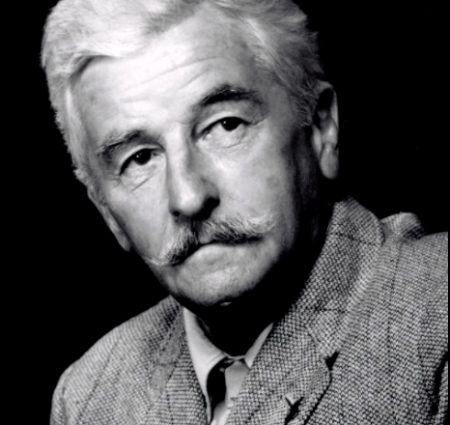

All aficionados of Southern literature know that William Faulkner’s literary landscape was the alluvial soil of the Mississippi Delta, the author’s “postage stamp corner of the world,” in his own memorable phrase. However, Faulkner’s biographers often overlook or downplay his connections to Tennessee. For instance, Faulkner’s great-grandfather and namesake, William Clark Falkner, was a Tennessean and Confederate war hero. The Nobel Laureate’s fondness for Memphis, his city to the north, is well-documented, too. His characters, especially in The Reivers, find Memphis a place of excitement and escape. In 1927, the writer made frequent trips to Bluff City, as Memphis is known to locals, where he was introduced to a madam named Bella Rivers, who offered him a job as landlord in her brothel, a satisfying arrangement because, in Faulkner’s words, it was “the perfect milieu for an artist to work in.” Memphis also was essential in helping Faulkner determine the geographical boundaries of his native South: “The South begins in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel in Memphis and extends down to the Gulf of Mexico.”

However, few scholars know or realize the amount of time William Faulkner traveled or stayed in the eastern part of the state, in particular, in or near Knoxville. Faulkner’s treks began in 1954 when his daughter Jill married Paul Summers, a West Point cadet. The couple chose Charlottesville, Virginia, home to the University of Virginia, as their place of residence. (In 1957 and 1958, Faulkner gave a famous lecture series at U. Va.) As Faulkner and his wife Estelle sought to visit their daughter when possible, the author plotted their course from Oxford, Mississippi to Jill’s Virginia home, by traveling “backroads” and state highways, given Faulkner’s antipathy to the burgeoning and soon-to-be ubiquitous interstate system. On the first journey, the Mississippian discovered the midpoint to be Knoxville. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a Holiday Inn sat at the corner of 17th Street and Grand Avenue.

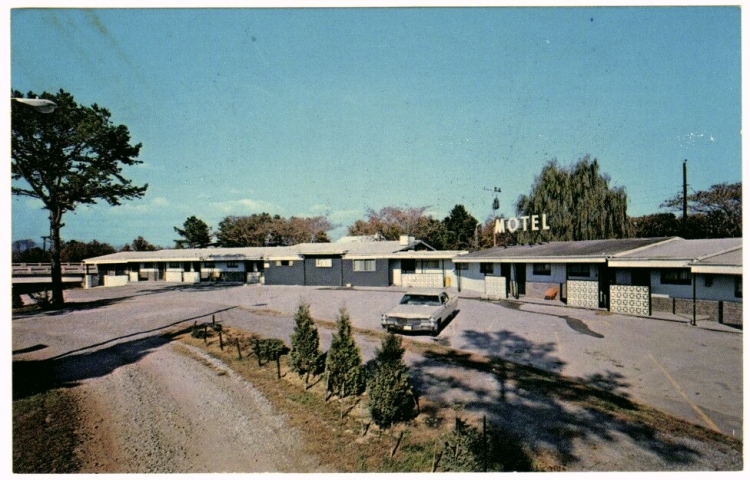

When Faulkner attempted to procure a room for the night, hotel staff declined to assign him one, pointing to a “No Pets Allowed” sign in the window. As an avid hunter, Faulkner apparently traveled with his two hounds whenever he took a road trip. Maybe oblivious, but the hotel management had just turned away the Nobel Laureate of the United States. Faulkner drove into the black night, he and Estelle staring at their headlights’ reflection on the surface of the Andrew Johnson Highway. Eight miles north of Knoxville, the couple spotted a glaring neon sign advertising the eight-unit Arrow Motel. Its marquis promised a phone and (black and white) TV in every room. Joseph Blotner’s two-volume biography of Faulkner states that the Faulkners stopped there regularly on their trips to see Jill, but doesn’t record any of the circumstances that took place there. The story would have ended as a footnote were it not for a student in my American literature class 20 years ago.

My student, a young man named Warren, approached me excitedly one day after class. We’d just spent the period discussing William Faulkner’s short story “A Rose for Emily.” Warren explained that he had a direct link to William Faulkner via his grandfather who’d once owned the Arrow Motel. Warren averred that his grandfather and Faulkner befriended each other. Together they’d sit in aluminum chairs on the lawn outside the office of the motor inn, swapping tales about their shared interests that included hunting, cat fishing and Jack Daniel’s whisky, of which the two men shared generous libations. Faulkner claimed to know Lem Motlaw, founder of the Jack Daniel’s distillery in Lynchburg, Tennessee. Warren’s grandfather never inquired about Faulkner’s work, having read somewhere about the author’s penchant for privacy. One day a reporter for the Knoxville Journal, who’d heard that Faulkner was staying at the Arrow, attempted to get an interview but was shooed off the premises by Warren’s grandfather who chastised him, saying,

“You didn’t want him in Knoxville when he tried to check into the Holiday Inn. You sure as hell aren’t going to bother him here.”

Toward the end of our conversation, Warren said he had a gift for me. From his pocket he produced what appeared to be a postcard.

“It’s a sign-in card signed by William Faulkner the last time he stayed at the Arrow Motel. I want you to have it.”

Turning it over in my hand, I inspected the card. Faulkner had been assigned unit three at the motel. He was driving a 1961 Nash Rambler. The date on the card was May 5, 1962 – almost two months to the day before Faulkner died of a heart attack. In the bottom right corner was William Faulkner’s inimitable scrawl. At that instant, I realized I held in my hand a living artifact.

“This is quite a trophy, Warren. Are you sure you want me to have it?”

“I’m sure,” he said. “I wanted to give it to someone who’d appreciate it.”

I thanked him profusely. Some time passed. Knowing that Faulkner’s admirers appreciate any new small scrap of information about him, I wrote a piece describing how the sign-in card passed into my possession. Editors at the Faulkner Review published the submission and a photocopy of the card.

Not long after, I received a call from a man identifying himself as the chief archivist of the William Faulkner Collection at the University of Mississippi.

“We read your article in the Faulkner Review,” he said, “and double checked the Blotner biography. Sure enough, Faulkner was at the Arrow Motel when you said he was.”

We weren’t off on a good foot. Was he challenging my scholarly integrity?

“The reason I’m calling, Professor Francisco, is that the Faulkner Archives here at Ole Miss has expanded beyond trade and limited editions to include manuscript materials and ephemeral items. What I’m saying, Professor, is that we’d like to have your sign-in card here in the archives.”

“Would you now?” I said, liking him less by the minute.

“Be reasonable, Professor. Faulkner was a native Mississippian.”

“Hold on,” I interrupted. “Lest I be remiss in reminding you: Faulkner’s great-grandfather was from Tennessee. Faulkner traveled extensively in Tennessee, and he set his Pulitzer Prize winning novel, The Reivers, in Memphis. He was in Tennessee when he signed the motel card.”

“What could you possibly want with that scrap of paper? It belongs to us!” he huffed.

“No, it doesn’t. It belongs to me. But here’s what I’ll do. The next time you come to Knoxville, drop by. For a nominal fee, I’ll let you view my little treasure before tucking it back safely in the catacombs of the Francisco Archives.”

A click on the phone signaled an end to our negotiations. To this day, I’m still the proud owner of a small piece of Faulkner’s legacy.

From time to time, I drive past the Arrow Motel, undoubtedly gaudier and shabbier now than it was when Faulkner stayed there. Still, I imagine him sitting on the lawn in a folding chair, puffing his ubiquitous pipe, sipping Jack Daniel’s whisky, and whiling away the time by recounting the story of a Mississippi-sized catfish that got away. As a literary fantasy, it doesn’t get much better than that.

**Featured Image: William Faulkner – find-a-grave

![William Faulkner's [[portable]] typewriter - southsideartgallery_Fotor675 scenes auto](https://wp-modula.b-cdn.net/spai/q_glossy,ret_img,w_675,h_401/https://www.appalachiabare.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/William-Faulkners-portable-typewriter-southsideartgallery_Fotor675-scenes-auto.jpg)

Really enjoyed this piece, especially your response to the pompous archivist. I suspect Warren’s gift says as much about the value of your teaching and your enthusiasm for literature as it does of his generosity.

Thank you, Jimmy! How kind.