On occasion, Appalachia Bare likes to spotlight some of our best submissions. “Elijah” was written by Daniel Dassow, the talented Third Prize winner of our 2020 George Washington Harris Short Story Contest. We are proud to present this submission for your enjoyment.

Daniel Dassow is a sophomore at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, where he studies English Literature, Creative Writing, and Religious Studies. He serves as a Staff Writer with UT’s editorially-independent student newspaper The Daily Beacon and is a member of the Chancellor’s Honors Program. His short story “Him” was runner-up in the university’s National Novel Writing Month short story contest in 2019.

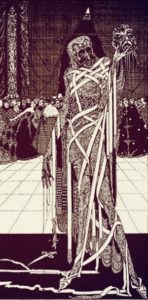

Elijah

“If a baby is born with a ‘veil,’ he or she will have the gift of prophecy.”

– Appalachian superstition

The night before they sent us home, I went to the little store on campus and had myself a shopping spree. There was $120 left on my student tab and I would have nowhere to spend it once I got home. I bought Slim Jims, Pop Tarts, potato chips, six packs of energy drinks, those gummies with a runny inside that burst when you bite into them — all the things my mother never let me have, like when she didn’t let me go out for the diving team because I could damage my beautiful head. As I filled my arms, I thought of the video of Greg Louganis splitting his head open on a diving board at the 1988 Olympics. They stitched him up and he was back on the board right after, but I probably wouldn’t have faired so well. I am fragile, my mother says. But powerful. I am my mother’s prophet, her Aryan dream boy, her immaculate conception, her little Elijah with whom she is well pleased. It was something about the look in my eyes when I first opened them. A veil, a distance or a gap that no amount of happiness could close. She says whenever she took a photo of me, it was like I was seeing behind her, beyond the camera into some separate dimension. It gave her chills.

I spent $119.78 at the student market and took the elevator back up to my dorm. I unloaded all the bags of junk food onto my roommate’s desk, since he left days ago. My mother seems to think I can see the future, but I never saw a pandemic coming. I interviewed international students about the virus for the student paper back in January, assuming Americans would never have much to say about it. And now here it is, and the school says I must leave tomorrow, pack my stuff up and head out of Knoxville, drive two hours back home to my mother and Papi and Grams, back to the cradle of the mountains.

When I tell people where I’m from, they have no frame of reference. I can’t place my home in proximity to any of the so-called Big Four cities, like the kids who live an hour outside Nashville and say they’re from Nashville. I just say I’m from near the North Carolina border. In Sociology 102, I’m told I live in a “crisis zone.” The city kids have read Hillbilly Elegy and I have not . When I mention that my grandparents live with me, they imagine toothless mouths and cabinets full of Oxys. They see a wasteland where pillheads OD and drive their trucks off the highway, causing traffic jams. I’ve never experienced those things. When I think of home, I think of the ridge we live on, how my house faces east and I can see the blue mountains dance under a pink sky when I wake up. I think of my mother’s bookshelves, full of Sylvia Plath and Gwendolyn Brooks, how she cried when I got accepted to the flagship university and cried again when I said I was going to major in English literature. For someone who was born and raised in Carter County, she invested so much time in helping me leave it.

I had to stop telling her my dreams around the age of six, because of how afraid she was that they might come true. I would bring in dead birds that I found in the creek bed behind our house and she would scream, tell me something about omens, make me take the decomposing bodies back outside. There were things she didn’t tell me. Like the time when she started having trouble sleeping, talked all about the kind of money she would make at her new job, the international travel it would entail and the luxury car I would get once I had a license. She was so happy she couldn’t stop talking. She worked as a school teacher and was stretched thin from raising me alone; she had no new job lined up. But I believed her, and then suddenly she left, off on a month-long vacation. I lived with my grandparents while she was gone in their small house in a neighboring county. When my mom came back, they sold their house and moved in with us since it would be safer, no questions asked. All this I accepted until my father called me on my birthday when I was thirteen. He didn’t talk to my mom anymore. This annual call was a bone she threw him. He sneered at me through the phone, asked me if I bought her vacation story, asked me if I knew why my grandparents had driven me to school every morning that first month of sixth grade, like I should be so lucky to have him to tell me the truth. I hated him. Then he told me about her stay at a mental hospital and I hated him more.

As I packed, I wondered if my mother would be on a high or a low when I got home. When I visited the campus psychologist after my first bout of insomnia, he said I should think of it that way. He warned me to get enough sleep, and that if I ever started having trouble sleeping, or if I couldn’t shut my “happy energy,” that I should seek help. He told me to inform those closest to me of the warning signs so they would know when I should see a psychiatrist. I never told my roommate any of this like he told me to. Mostly he and I only talk in passing. He is from Memphis, so he says he’s “seen shit.” He sometimes does a boxer crouch and pretends to punch my stomach before he goes to class.

I was putting my books into a cardboard box when my phone rang in my pocket. The screen lit up with a picture of me and my mom taken when I was six and had just won my first blue ribbon on the swim team, her crouched down next to my dripping shivery body. There was a gap between each of my teeth. When I answered, she started asking questions.

“When are you going to get here?” she asked. “I’ve been so lonely here.”

“Talk to grandma or grandpa,” I said.

“No fun. Seriously, when I should have dinner ready?”

“I thought I told you, I’m not leaving until tomorrow,” I said.

“What? I had this all planned out, Eli.”

“I should get there around noon tomorrow. I’ll leave early, I promise.”

“What are you even going to do there tonight? Isn’t campus like empty?”

“Mom, I’m leaving tomorrow.”

“Well now I have all this soup and no one to share it with.”

“Eat with grandma and grandpa,” I said. “Curl up with a book.”

She sighed, the elation in her voice gone.

“Text me when you leave tomorrow, Big Boy. Have a good last night on campus. Love you.”

I said “I love you too,” but she hung up a fraction of a second before I finished, just as I started to say the word “too.”

Even with the love between us, even with our shared dream of leaving Carter County (Had she given me this dream? Was it even mine?), there was still so much we hadn’t told each other. I hadn’t mentioned that I loved being in Knoxville so much that I didn’t want to come home, that I wanted to wait until the last possible moment to leave. I wanted to postpone the moment when I would have to face my grandparents’ questions and my mother’s moods. I knew that would break her heart even though she wanted me to be here. I also didn’t tell her about the recurring dream I had been having since the pandemic came and we were told we had to go home. I didn’t want to worry her. I wanted to keep the promise I made years ago not to let her in on any of my visions that might disturb her.

In the dream, I’m running through our house. It’s just me and her living there again. I’m six years old and she is chasing me and everything is good. But then I turn the corner into the bedroom at the back of the hallway where Papi and Grams sleep and everything turns black. There is a deafening noise and I am sucked in. I look back towards my mother, and she is crying. Then she is laughing, tells me she was just kidding like it’s all a joke.

The drive back home was the same as it was when I came back for Thanksgiving and for Christmas. I got on 81, switched off onto 26, rode that until Johnson City, and then got on 321 for home. I forgot my auxiliary cord in my dorm and my car’s too old for Bluetooth, so I turned on the radio. It was either music or the virus. I listened to the news for a few minutes before I got tired. They all said the same thing: social distance if you can, the elderly are at a higher risk, watch out for those college students driving on their way home, John. Something tells me they’ll be awful sad to leave. As if sadness were a kind of drunkenness.

It was hard to imagine something microscopic screwing up my life this bad. For the next few months, I planned to read a lot and slowly make my way through my junk food stash, which I would hide in my room. My mom would want to cook with me no doubt. She’d want to go on hikes and go to readings at the local library like we’d always done, hearing little shitty things that local authors had self-published. We always liked going and snickering at the tired prose and terrible poetry. Maybe they’ll have to stop doing those too, I thought. Everything will stop. The world will halt, and all our lives will be put on hold, I thought.

I pulled into our gravel driveway without ceremony. No one came out to hug me, not even grandma. I walked through the front door carrying only one bag, figuring I could get the rest later. I didn’t see anyone until Mom came out of the back bedroom and walked towards me. There was a blank expression on her face, and she walked with her shoulders down. Still, she hugged me tightly. I thought: low. I thought maybe my tone over the phone was what did it.

“I’m glad you’re home.”

“Where are grandma and grandpa?” I asked.

And then I heard it, coming from the back room. The hacking, the death rattle. I pushed past my mother and ran to the back bedroom. When I peered in, I did not see my Papi. Only Grams lay there on her back coughing and gasping for air. My mind raced through all the evasive calls from my mom, the way she hadn’t answered my questions about whether Papi and Grams were ok. I thought of the way she was still a child. The way the elderly were at higher risk, the elderly were at higher risk, the elderly were at higher risk. I turned around to see her standing in the doorway, and I stared straight into the face of her kind of protection — avoidance, prohibition.

“It wasn’t worth worrying you,” she said, with tears coming to her eyes.

And for all of me that wanted to yell and ask where my grandpa was and how she let it happen, there is another part of me that blames myself. Because I have known all of this, all along.

** Featured Image by Christopher Campbell on Unsplash