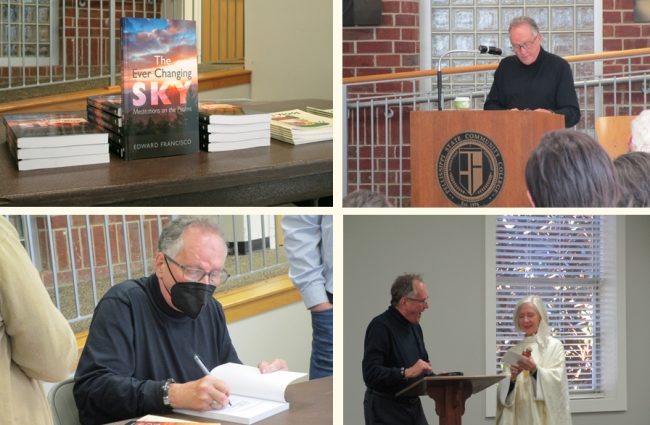

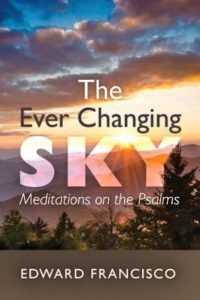

I recently had the honor of conducting an interview with our own Edward Francisco about his new book The Ever Changing Sky: Meditations on the Psalms (Wipf & Stock, 2021). Much of that interview is found below. The entire interview will be available this Friday, November 19, on Edward Francisco: The Official Website, with the following additions:

- One of his favorite meditations

- A further take on questioning faith and The Book of Job

- An anecdotal experience teaching “Christology: Images of Jesus.”

- How these meditations strengthened his own faith

- Discussions about his brilliant poem, “Mabon”

- His writing process

- The book’s publishing journey

The Ever Changing Sky is available at Union Ave Books, Barnes & Noble, Wipf & Stock, Christianbook, and Amazon.

Although this book should appeal to a wider audience of readers

seeking to uncover sacramental graces in everyday life,

The Ever Changing Sky is especially meaningful

for those wishing to contemplate their lives in a spirit of wakefulness.

— Blurb from back cover

1.

AB: You mentioned The Ever Changing Sky took over 10 years to write. Given that you’re a contemplative, deep thinker, what was the initial motivation for writing it?

Ed: My initial impulse was simply to meditate on the psalms in some way that they magnified or clarified events that were occurring in my life. I tried to see my events, my occurrences, whether they were with my family or friends or with my vocation in the light of something larger, and the psalms provided me with that lens for doing so.

I really began out of impulse a recognition that every moment of my life was important and that it was incumbent on me to be keenly aware, to bring mindfulness to every perception, observation, thought that I was having. And obviously I was trying to see the relationship between my present with the present of an earlier age, the ancient Israelites, who were a people despised, a people who were exiled, who were forced into remoteness, and at the same time were commanded to have hope and faith and obedience. Obedience was a very important part of the Jewish covenant with God. Their god promised that he will bless them so long as they observe the covenant, so I was trying to figure out what kind of covenantal relationship I had with various aspects of my life, my life as a husband, as a father, as a teacher, all of the obligations I sought to fulfill in middle age.

2.

AB: What was the most difficult part of writing the book? I know you reached the 75th Psalm and decided, “I might as well . . .”

Ed: Well, and I think that’s important. There were periods of malaise where I would forget about the meditations and just lived on, lived my ordinary life, and then something would tug me back and I would look at the meditations and see where I’d left off, and then picked up from there. I think one of the enemies of the spiritual life is acedia, the idea that you’ve reached a plateau, now where do I go from here?

You and I have talked about whether or not we really believe in God. Well, the philosopher Hannah Arendt talked about refined atheism – the idea that you do have to give up the old notions and the old assumptions about God, and really walk in the valley of the shadow. I can’t embrace God as anything but the Newmanist quality of awe. God is not my friend. God is not somebody who can be bribed. And that’s terrifying. It’s terrifying. And Arendt says it’s necessary to experience those, for lack of better words, bouts of atheism, where you don’t know you’re questioning. And that questioning is right and proper, no matter the outcome.

3.

AB: What do you hope readers will take away from The Ever Changing Sky?

Ed: I want the book to align with their journey toward authenticity, to ask the ultimate question, to not be afraid to ask those questions, in the light of the questions I’ve asked. It’s not a book of how-to devotions, as I’ve indicated today. I want it to resonate with people on a human and spiritual and existential level. It’s not for people who don’t want to be aware. I just want to be able to contribute to people’s trek toward awareness. I have no  more ambitions for the book than that. I certainly didn’t write it – I wasn’t trying to imitate anybody. I wasn’t trying to imitate Augustine’s Confessions, or Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain, although I certainly have read those texts and I’ve been influenced by everything I’ve ever read, and everything I’ve experienced, and everything I’ve taught.

more ambitions for the book than that. I certainly didn’t write it – I wasn’t trying to imitate anybody. I wasn’t trying to imitate Augustine’s Confessions, or Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain, although I certainly have read those texts and I’ve been influenced by everything I’ve ever read, and everything I’ve experienced, and everything I’ve taught.

One of the premier experiences and challenges for me was a course I taught at Pellissippi in the special topics program of that time called “Christology: Images of Jesus.” And I sought to seek Jesus out in as many manifestations as I could for the people in that class, and for them to do the same.

At that time, we had more wiggle room to offer courses that were unconventional. I also taught a course called “The South in Literature and Film,” and used the anthology that Linda and Robert and I had edited for Prentiss Hall. The curriculum, of course, has become too cookie-cutter now. I couldn’t offer a course in Christology, if I were still teaching, if I wanted to.

I was a little worried today about the reading because I thought, “Okay, I’ve got some young people in here,” and I’m making no apologies about being a Christian Apologist. But they were fine with it, they really were. And I kept my eye on them. And that was one of the reasons why I said “You don’t have to be a purporting Christian to have Christ consciousness.” If I gave them a way to embrace their own inherent spirituality without forcing it on them, then I was successful.

4.

AB: What is the most surprising thing you’ve discovered about yourself while writing the book – or doing the readings?

Ed: How much I don’t want to be perceived as holy or holier than thou. A saint is someone who is most fully him or herself. Now, to my thinking, that’s a superb definition. The saints were pretty irascible, ornery people, by and large. And if I can count myself in that group, okay, I’ll hold my nose and say, “Well maybe there’s some possibility of me being saintly in eons from now, okay?” But I discovered through grace, maybe a smidgen of humility, I think we all have to walk away at some point and say, “I’m not all that.” And I don’t want to be those people who are all that.

I offered the caveat that I’m neither as good nor as bad as the man who wrote these meditations. And I shiver at what people are going to think of me in some of them. The young woman who typed them originally, said to me, “You know what I like about these?” And I said, “No, what?” She said “You don’t try to explain yourself away. You’re just straightforward. You’re truthful about you.”

These psalms may have helped me to point to what I don’t want to be, and what I’m perfectly fine being quiet around. At this point in my life, I don’t have anything to prove. In the relatively small scheme of things, I’ve been successful. Everything I’ve attempted to do. For one of your former students to say, “You’re amazing,” that just lifts you up.

5.

AB: You’ve written novels, short stories, books of poetry, essays, plays, and have features in journalism. Did you find this endeavor differed from these genres? If so, how?

Ed: No, and let me explain why. I’m a writer, and not a writer of . . . I know poets, for example, who can’t write prose. I know plenty of prose writers who’ve never attempted to write a poem. And a play is one of the most rarified  writing assignments I’ve ever had, even as rewarding as it is when brilliant actors and directors take your work and fix it. It’s still overwhelming. So, I have enormous respect for playwrights. And, to be honest with you, there aren’t a lot of great plays.

writing assignments I’ve ever had, even as rewarding as it is when brilliant actors and directors take your work and fix it. It’s still overwhelming. So, I have enormous respect for playwrights. And, to be honest with you, there aren’t a lot of great plays.

I’ve never niched myself. Now, people have niched me. Linda [my wife] will tell you I’m a great poet, if not a great human being. And [my son] Gabriel will say, “Dad, your best genre is poetry.” But I think I’m a pretty damn good raconteur. I’m a good storyteller, whether it’s tall tales or mystery fiction, I enjoy it. The problem about writing poetry is that you’re only a poet when you’re writing a poem. All you want to do is finish the poem, get that monkey off your back, at which point you’re no longer a poet, and you sit and bite your fingernails, never knowing if the impulse will strike again or not.

6.

AB: What were some of the challenges you faced with the manuscript?

Ed: That I had finished it on the cusp of the pandemic and the wheels of publishing stalled on the track. They were so slow responding and I was worried because I was trying to keep my contract deadline. Fortunately, my editor said don’t worry about it, they’re behind, too. And, as you know, the line editing, which you and Linda did so spectacularly was secondary to the formatting required. And you cracked that code. I don’t know how you did it.

Delonda: [Laughs] I don’t either. I did research, I think is what it was.

Ed: You did. You always research which means your writing is always on solid ground. But you figured it out. I swear, if I had had to do this alone, it wouldn’t be out today. So, was that a challenge? Sure. Even though I had finished writing the book when the pandemic broke.

The other challenge, on a more mundane basis, was rearing a family, teaching classes, being a husband, doing chores, and finding time when I could. I’ve heard writers who’ve said, Walker Percy in particular, said “I’m amazed at gifted teachers who also write.” He said “I was a lousy teacher. I couldn’t teach and write.” But you know I always managed that pretty well. You know how I did that? I gave assignments to my students that I could dovetail into my own work. So, what I was asking my students to write was some facsimile of what I was writing at the time. So, when I gave an assignment to write “A Blank,” I wrote it, too. And that’s how I solved the problem, if there was one.

The other challenge, on a more mundane basis, was rearing a family, teaching classes, being a husband, doing chores, and finding time when I could. I’ve heard writers who’ve said, Walker Percy in particular, said “I’m amazed at gifted teachers who also write.” He said “I was a lousy teacher. I couldn’t teach and write.” But you know I always managed that pretty well. You know how I did that? I gave assignments to my students that I could dovetail into my own work. So, what I was asking my students to write was some facsimile of what I was writing at the time. So, when I gave an assignment to write “A Blank,” I wrote it, too. And that’s how I solved the problem, if there was one.

Percy said, once again, “Writers go into a state. They orbit, within that hypercerebral state of being, but then they have to come down.” That’s very hard for writers. You orbit but you have to decelerate and come down. And that was never very hard for me. Now, how did Percy and Faulkner come down? They drank. For six weeks. You go out and you write The Sound and the Fury for six weeks of sobriety, or relative sobriety, then you go on a binge for six weeks, because you don’t orbit successfully. Now, for the most part, I do a pretty good job of reentry, as Percy called it.

7.

AB: Do you have future projects? Can you discuss them a bit?

Ed: I’m researching Edgar Allan Poe in Charleston. He was in the army for a year and a month there, and he wrote “Annabel Lee” about a Charleston woman named Annabel Lee Ravenel. The Ravenels are an old family, an old wealthy family, antebellum and after. Even now, they’re the big wigs in Charleston. And Annabel Lee was Annabel Lee Ravenel, who had been promised to another man but who fell in love with the rogue Edgar Allan Poe. And the father forbad Poe from seeing her . . . But they met in the cemetery for their trysts. She’s buried in the Unitarian cemetery there. When Poe got stationed at Fort Moultrie, (In other words, the dad had enough influence to get him restationed.) she took sick and died. And, when he’s talking about “the kingdom by the sea,” that’s Charleston. That’s Sullivan’s Island. Now, why wouldn’t I exploit that? I’m going to exploit it from the perspective of quantum theory, of moving about in time. Charleston is a nexus of energy. I know it is. I suspect my backyard, the park, is that place, too.

Delonda: You can feel it, you know, in certain places.

Ed: I gain energy from it every day.

The following is a video of Edward Francisco’s first reading at The Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd in Knoxville, Tennessee, and is provided courtesy of the church via Facebook. (Thank you Amma Dorrie Pratt and Ruth Anne Hanahan!)

**Featured image photographs by Delonda Anderson.