Clark Air Base, on the island of Luzon, Philippines, rumbled as if a herd of water buffalo were stampeding the flight line. The multistory, 13th Air Force Medical Center was in flux—the walls swayed and the floor bucked beneath us. The five newcomers, sitting in a semicircle around the hospital commander’s desk, froze as the colonel’s orientation briefing came to an abrupt halt. For an instant we stared at each other in stunned silence. As the earthquake began to register in dilated pupils and furrowed brows, the commander piped up, “I suggest we get under the doorframe!”

A dash for the office door, the narrow frame filled, and I realized no room was left for me. I assumed a surfer’s position in a corner and rode the waves. The commander’s desk rattled; his military knick-knacks crashed to the floor. I watched, fascinated, as a crack widened on the opposite wall and the parking lot undulated outside the ground-level window.

The date was July 16, 1990, 4:26 p.m., a few weeks after my arrival at the largest U. S. Air Force base overseas. The earthquake was just the latest tumult to roil the base. Tensions were high because negotiations with the Philippine government were pending over the future of the base. On May 13th, two Air Force airmen had been shot, assassinated outside an off-base hotel by communist New People’s Liberation Party guerrillas. Travel was severely restricted, and all incoming personnel were required to live within the compound. Personnel still living outside the gate could only travel to and from the base and their homes. Despite a huge contingent of security police patrolling behind eight-foot-high concrete block walls, thieves routinely managed to steal from the facilities. Even the hospital kept locks on the dumpsters to stymie looters from carrying off medical waste.

I took the security restrictions seriously; yet, at my last assignment, I had lived in an inner-city apartment bordering the University of Maryland at Baltimore (UMAB) campus. Something like 62 murders had accumulated in Baltimore before I departed. In Luzon, the likelihood of being shot seemed lower, and I would at least know why I was targeted.

Courtesy of an Air Force Institute of Technology scholarship, I had graduated in May with a UMAB master’s degree in trauma and critical care nursing. Already a captain, I owed the USAF four more years for the education, and I was eager to get some additional critical care experience. My equally eager friend, Diane, also a USAF captain and a graduate from the same program, landed in the intensive care unit (ICU), while I filled a slot as an assistant charge nurse on a very busy surgical ward with a lot more but less critical patients.

Back in the commander’s rocking office, the seismic onslaught subsided in about a minute (on an interminably slow clock). The structure, built to withstand earthquakes, was still intact and functional, if a bit worse for wear. The colonel immediately dismissed us to go check on our units.

I rushed up the stairs to 5-S, the fifth-floor surgical ward. A television and several picture frames were smashed on the floor. A couple of elderly Filipinas were crying and nervously pacing the hall. An airman had yanked out his IV, jumped out of bed and attempted, unsuccessfully, to dive under it. I would find him later, hunkered in the corner of a doorframe, fervently reading his Bible. A periodically swaying sign in the hallway alerted us to aftershocks, milder than the initial jolts but still nerve-racking from our perch on the fifth floor. Despite the chaos, we were still in business.

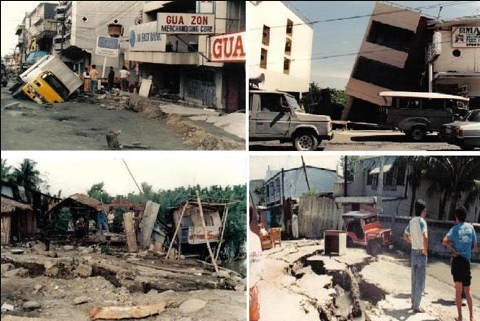

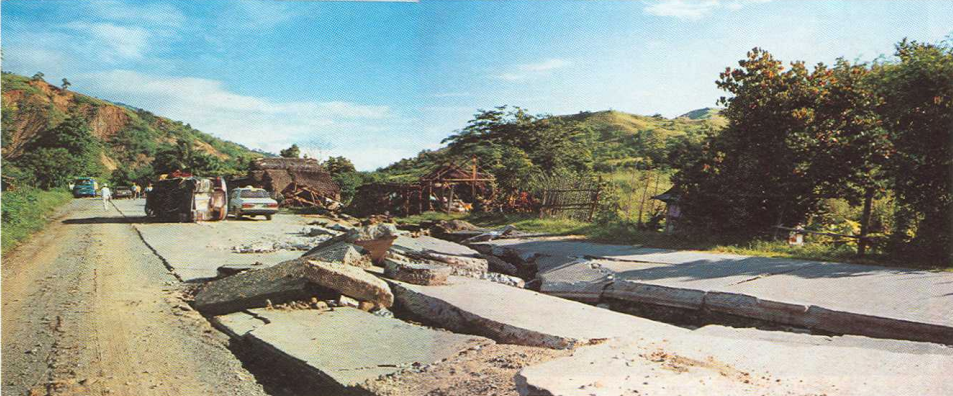

Clark’s mobile tactical hospital team deployed 102 miles north to assist in Baguio, a resort area close to the epicenter of the 7.7 quake on the Richter scale. Many buildings, including schools and hotels, had collapsed, resulting in hundreds of horrific injuries and fatalities (details in this CDC report). I had made reservations just that morning for a weekend in Baguio at Camp John Hay, a military recreational facility where we were still allowed to travel. I had tried to get there once before but was thwarted when a typhoon washed out the roads. Now the main roads to Baguio were blocked by landslides. Later that night, I was pulled to the emergency room to help care for several busloads of less critically injured earthquake victims, some with bone fractures or dislocations.

I arrived for my second shift the following night to learn a 17-year-old boy with gangrene and both legs amputated had died in surgery. Seven injured people from Baguio were bedded on 5-S. A teen had been in a bus that tumbled over a precipice. Her “rescuers” dragged her out of the bus and up to a house, abrading most of the skin off her legs in route. My gravest patient was a stocky, middle-aged waiter who had been pinned beneath a concrete slab in the collapsed Hyatt hotel. His skull, spine and left leg were fractured. He was bleeding internally. I ended up giving him a total of four units of blood and maxed out the doses of his analgesics in an attempt to dull his agonizing pain.

By my third 12-hour night (6 p.m. to 6 a.m.), I was exhausted, not from the long shifts, our standard routine, but from lack of sleep in the daytime. The air conditioning in my tropical quarters was out of service and a jack hammer incessantly pounded on the floor below. The hotel waiter’s family helped out. As typical of strongly-bonded Filipino families, a member tended him at all hours of the day: feeding him, bathing him, massaging his feet. Some nurses were rigid about visiting hours, I was not one of them. Dealing with families could be tiresome (and crowded) at times, but their support helped the patient to recover. The downside was the doting families’ ministrations had to be weaned off when it was time to rehab their loved one for discharge home.

I was on a list of volunteers to relieve the tactical hospital team in Baguio. We never got the call to go, but the ICU continued to treat the more seriously injured victims. I was pulled down to the ICU one night to help the overburdened nurses. Six patients were intubated and dependent on ventilators. My patient, less critical, was breathing on his own. A brain-injured, multitrauma patient’s ventilator suddenly lost pressure. Unsure of the cause of the malfunction, his nurse called the respiratory therapist, disconnected the tubing and manually ventilated the man with a bag valve mask. As they were working to correct the problem, two more ventilators began to lose pressure. We hooked-up one of the patients to portable oxygen and began moving the second one to another bed. Just as we got him settled in, the remaining ventilators wheezed off. By then, the civilian staff responsible for the central oxygen system had been notified. We all scrambled with portable oxygen tanks and mask bag valve systems to keep the patients alive until the maintenance guys, who apparently hadn’t been monitoring the pressure in the system, causally ambled in to recharge the tanks. The patients survived; we hoped the person responsible for the oxygen snafu would not be so lucky.

By early September, the last of the earthquake victims from the ICU, a 17-year-old boy, was transferred to 5-S. His right arm was amputated, and he had suffered internal injuries, including a collapsed lung. We administered tube feedings and encouraged the debilitated, 85-pound youth to eat.

The Hyatt waiter, after a spinal fusion, was up and about in a back brace. Smiling, he asked me, “Will you remember me when you go back to the States?”

Over thirty years later the answer is still, “Yes.”

I was now on day shifts and 5-S was back to a busy revolving door routine of surgeries. On one memorable day that stretched my shift to 14 hours, we had 11 admissions, 7 discharges, and 8 or 9 surgery patients transported out and back from the operating room. I barely managed to give the minimum of care to my assigned patients. One airman, recovering from brain surgery, told me he was in Kuwait and the month was March. I knew how he felt. Maybe if I checked on him more often, he wouldn’t have peed in the bed and pulled his IV out. As I gave my end-of-shift report, I realized I didn’t know anything about my new patients admitted by the charge nurse during the rush.

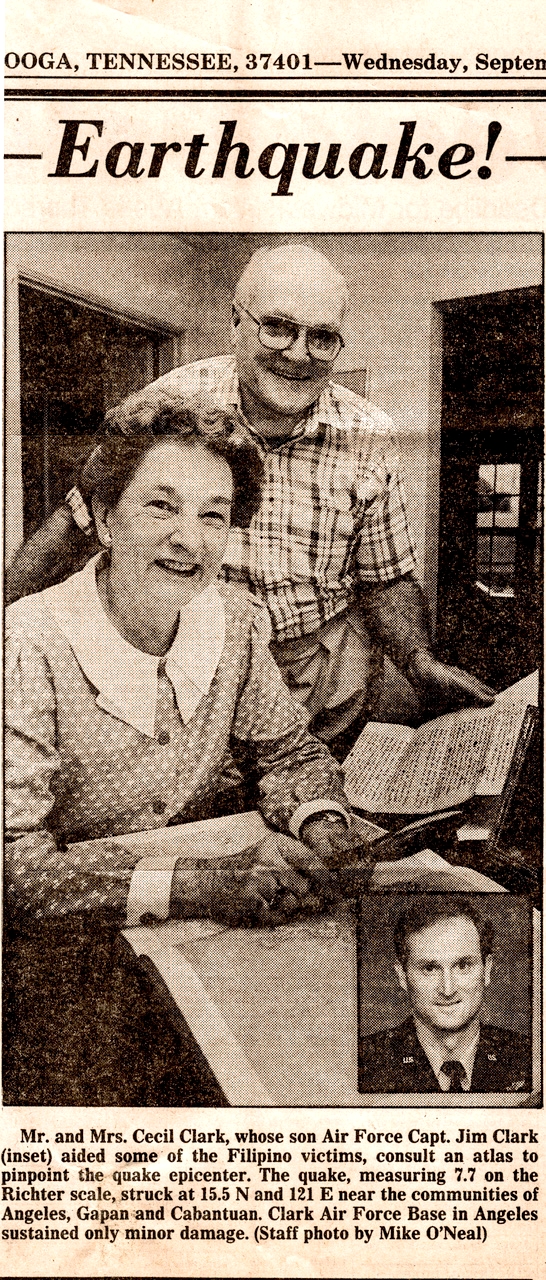

My sister, Lin, at the time a staff writer for the Chattanooga News-Free Press, sent me a surprise: a copy of her article, “Earthquake!” sourced from the letters I had sent home. Since I hadn’t gotten preapproval to talk to the press, I wrote the family back:

“I enjoyed the earthquake article; although, had I known I would be quoted, I would have been a bit more careful of what I wrote. I just hope nobody of importance in the military reads it. If so, Lin’s next bit of nepotism may read, ‘Former Capt. Clark Booted Out of Air Force’ . . . (Soon to be published: ‘Clark’s Letters from Ft. Leavenworth Prison’).”

Later, I wrote a remark that would come back to haunt their family wiseass:

“By the way, are you sure you want me to call after every natural disaster? According to the Stars and Stripes, the R.P. sits astride 10 major earthquake faults, has 22 active volcanoes and averages 20 typhoons a year.”

In April of 1991, Mount Pinatubo, a volcano west of Clark AB which hadn’t erupted in 500 years, lofted smoke signals hinting of more shake-ups to come. The earthquake, like this story, was a prequel to a more explosive event (next up: “Disaster in the Philippines, Part 2: Volcano”).

**Featured image: Akın Akdağ, Pexels

Jim, absolutely fascinating!!! I never knew.

Thanks Dan, We’ve come a long way from those Graham street days. I joined the Air Force in part for travel and adventure, and sometimes I got more than I bargained for.

Jim, Wow–great article! Kept me riveted. Little did I know how little I knew about the Philippines. Time I learned!

Thank you Linda—more to come!