The next part of our journey transports us on a cold December day to Briceville, Tennessee – just a hop, skip, and a jump away from Coal Creek. We arrive at the Cross Mountain mine almost ten years after the Fraterville mine disaster.

Coal camps in Appalachia were cheerful in December. Christmas garland most likely bedecked the walkways. Various tin toys, dolls, and trains adorned company store windows as Nativity plays and Christmas parties neared and snowfall descended, soft and magical. Camp houses might have adorned their walls with children’s artwork, Christmas cards, or holiday-themed newspaper. A family trudged the backwoods to find the perfect Christmas tree. Once it was cut down, dragged home, and set up, the tree was most certainly decorated with stringed popcorn and a few homemade ornaments. Children gazed at the empty space beneath and filled their imaginations with teddy bears, dolls, jigsaw puzzles, Binny & Smith crayons, and tin cars. A coal miner had to work additional days to afford a merry Christmas.

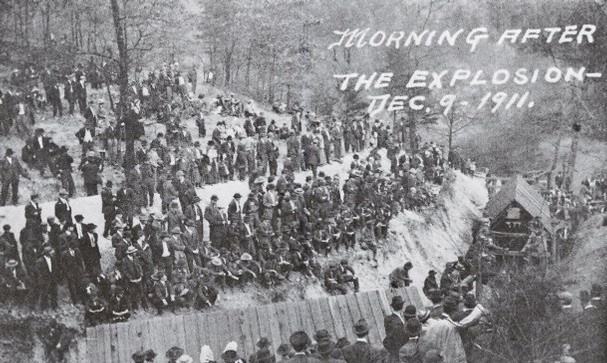

On a frosty December 9, 1911 at around 6:30 in the morning, eighty-nine miners entered the Cross Mountain mine with Christmas hopes of their own. On that December day, less than an hour later, a violent explosion occurred in Cross Mountain, evoking memories of the Fraterville mine disaster in 1902. Only five men came out alive.

The Cross Mountain mine at Briceville, located nearly five miles from Coal Creek, was owned and operated by the Knoxville Iron Company and had been operational for over twenty years.1)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 10). Two Hundred Lives Snuffed Out in East Tenn. Mine Disaster. The mine was labeled a “Class B” 2)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 10). Briceville Mine Inspected Twice in Four Months. drift mine 3)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1912, Apr 19). Chief Inspector Reports on the Briceville Mine. pg 14 that produced about five-hundred tons of coal each day and never “had a serious accident.” 4)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 12). Five Entombed Men in the Cross Mountain Mine are Found Alive. pg 10 The mine was quite large and far-reaching. The area where the men worked was five-hundred acres, two-hundred fifty of which was a functioning work area. 5)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1912, Apr 19). Chief Inspector Reports on the Briceville Mine. The shaft went down two miles inside the mountain.6)The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 10). Hardly One Ray of Hope for 207 Men Entombed in The Tennessee Mine. The entryways were large – from 2500 to 3000 feet. Brattices, or, “partitions used in a mine passage to confine the air and force it into” the work area, were mostly “slate and waste material ten or twelve feet thick and packed tight.” 7)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1912, Apr 19). Chief Inspector Reports on the Briceville Mine. Near the entrance, a seven foot electric fan sat one-hundred feet down in an airshaft and was used to force out bad air and bring in good air. 8)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1912, Apr 19). Chief Inspector Reports on the Briceville Mine.

The mine was supposed to be inspected “every 60 days.” 9)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 10). Briceville Mine Inspected Twice in Four Months. Two new mine inspectors were hired: State Inspector George Sylvester on June 1, 1911, and Deputy Inspector Richards on July 14. The mine had not been evaluated all year before the two men were employed. After their hiring, the mine was inspected on August 3 and October 30 and “no dangerous conditions were noted.” 10)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 10). Briceville Mine Inspected Twice in Four Months. J. F. Hatmaker performed another inspection six days prior to the explosion and the mine received “a good review.” 11)The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 10). Hardly One Ray of Hope for 207 Men Entombed in The Tennessee Mine.

The initial blast caused flames to shoot out from the mine openings up to three hours later. Panic and fear spread just as fast as the explosion itself. The number of workers on dayshift at Cross Mountain were approximately 126 to 156 men. 12)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 10). Briceville Mine Inspected Twice in Four Months. At least eighty-nine men descended two miles to their working area. Others escaped because they hadn’t fully entered the mine before the explosion occurred. 13)The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 10). Hardly One Ray of Hope for 207 Men Entombed in The Tennessee Mine. One man, Hugh LaRue, avoided the disaster because his wife begged and urged him to stay home. Mrs. LaRue told him about a dream she had where she “saw scores of miners with their heads blown off being carried out of the mine entrance. That she and her little children stayed at the mine’s mouth watching the unfortunate coal diggers being carried out.” 14)The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 10). Hardly One Ray of Hope for 207 Men Entombed in The Tennessee Mine. pg 2 Though a Knoxville Iron Company official “minimized the extent of the explosion and . . . declared that they believed many if not all the men in the mine would be rescued alive,” the community knew deep down the ominous occurrence meant certain death for all of the men in the darkness. 15)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 10). Two Hundred Lives Snuffed Out in East Tenn. Mine Disaster. pg 8

Family members hurried to the scene at the mine entrance. Wives and mothers moved “as close as the restraining ropes would permit around the entrance of the mine . . . they begged to be allowed to enter the shaft and search for their husbands and sons.” 16)The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 10). Women and Children Wailing at Mouth of Ill-Fated Mine; No Hope for Entombed Miners. p. 2 C. Miners all around Coal Creek stopped working at once and rushed to the site. As a matter of fact, volunteers came from every mine in the region: Jellico, Oliver Springs, Middlesboro (Ky), and southwest Virginia. Estimates reveal at least ten thousand people – miner and non-miner – came to offer assistance of any kind. 17)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 11). Eight Bodies Taken from Ill-Fated Mine; No Hope of Rescue. pg 7

Search, rescue, and recovery teams were immediately established, organized by George P. Chandler, president of the Tennessee Coal Company. Chandler arranged the groups “in squads of about 50 men each.” 18)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 11). Eight Bodies Taken from Ill-Fated Mine; No Hope of Rescue. pg 7 Every crew worked two hour rotations inside the mine. The first rescue efforts were stalled due to debris. The teams had to excavate it by mule since the electric cars were destroyed. Flames and fires were another deterrent that had to be extinguished before continuing. It was imperative to “remove the debris and force fresh air into the inner most recesses of the mine,” not only for the miners who could have survived the blast but also for the rescuers who risked their lives. Poison gas (carbon monoxide) halted the rescue process, but some were undeterred, working without food, sleep, or pay, until “they were carried out overcome by the noxious gasses.” 19)The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 11). All Dead. A few of the rescuers even had to be resuscitated by using a “pulmotor” (essentially, an oxygen machine).

Better rescue equipment and methods were used at Cross Mountain, some for the first time. The United States Mine Bureau developed mine rescue crews who came to Briceville with twenty-five “oxygen helmets,” the equivalent of today’s gas mask. These rescuers were able to go farther distances into the mine for longer periods of time. Canary birds were first used at Cross Mountain 20)Popular Mechanics. (1912, Mar). Canary Birds in Mine-Rescue Work. p. 355. Retrieved from here to detect the presence of poisonous gas. Initially, miners thought this idea was ludicrous, however, after seeing the method’s success, they soon realized the bird’s usefulness. A miner without an oxygen helmet was “not permitted to enter chambers in which the birds cannot live.” 21)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 14). Forty-Nine Men Entombed in Mine Brought Out Dead.

Eighty-two men died suddenly and violently from the explosion. Two other men who survived the blast succumbed to carbon monoxide. It was reported that rescuers heard them “knocking on the walls of the mine.” 22)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 14). Forty-Nine Men Entombed in Mine Brought Out Dead. The situation seemed hopeless for the rescuers and the community. Almost sixty hours after the incident, five miners were rescued alive: William Henderson, Milton Henderson (son), Arthur Scott, Theodore “Dore” Irish, and Irving Smith. William Henderson, who, incidentally, was found by rescuers sitting and smoking his pipe, 23)The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 12). Thought Dead, Buried Miners Are Found Alive. said this about the group’s experience:

With our coats we fought back the after-damp that came through the cracks in the brattice and then stuck our coats and other articles of wearing apparel in the hole of the brattice . . . We remained in this room quietly for several hours burning one light and taking turns eating. Late Saturday evening Arthur Scott and Dore Irish left the room and attempted to make their way back and reach the entrance of the mine through the overpass. That was the last we saw of them. The next morning, we made our way, the air having been purified by the fan into the entry . . . ran into gas and were forced to go back . . . where the air was pure. We remained there until discovered tonight. 24)The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 12). Thought Dead, Buried Miners Are Found Alive.

All of Briceville was overjoyed. Women rushed to see if one of their husbands had been found, but “the wives of none of the rescued men were there, some of them being ill and hysterical. The scenes at the homes when the men arrived were affecting.” 25)The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 12). Thought Dead, Buried Miners Are Found Alive. pg 13

Sounds of grief renewed when the train from Knoxville came to Briceville carrying 175 coffins. 26)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 11). Eight Bodies Taken from Ill-Fated Mine; No Hope of Rescue. pg 7Such a numerous volume had to be a jarring realization for the community. Bodies were so badly disintegrated, they couldn’t be prepared for burial, so they were all buried in their work clothes, “consigned to their graves unrecognized and unidentified by their widows and mothers.” 27)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 14). Forty-Nine Men Entombed in Mine Brought Out Dead. pg 2 A new graveyard was created at Laurel Branch for the miners who lost their lives. Like Fraterville, the graves form a circle – that ancient symbol of eternity – around a monument that reaches toward heaven and honors eighty-four brave souls.

Inspector George Sylvester was chosen to investigate the cause of the explosion and presented his conclusions to Tennessee Governor Ben Hooper. Sylvester believed the blast was caused by “mainly, if not wholly, a dust explosion,” ignited by “a small amount of gas present in the air.”28)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1912, Apr 19). Chief Inspector Reports on the Briceville Mine. But he couldn’t “decide with any degree of certainty the exact point from which the explosion started or its initial cause,” but, based on the evidence he found, it spread “in the lower part of the mine from one entry to another . . .” Further, he said, admittedly without evidence, a hefty chunk of coal might have fallen in one of the rooms the previous night, circulating dust that could have been “ignited by the lamp of the miner working in this place.” 29)Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1912, Apr 19). Chief Inspector Reports on the Briceville Mine.

Well, this third installment ends our Coal Creek journey. I hope I was able to show you a little more about the region, about coal mining, coal miners, and their families. I hope you visualized an Appalachian community coming together, near or far, rich or poor, from various nationalities, to offer help or to stand on principle. Thank you for walking with me. I’ve so enjoyed travelling with you.

If you’d like to learn more about Coal Creek or coal mining, please visit the following websites, or, better yet, come visit the area and see.

Coal Creek Watershed Foundation (What a great source of historical and community information here!)

Historical Markers in East Tennessee (take the Briceville, Fraterville, and Rocky Top tour)

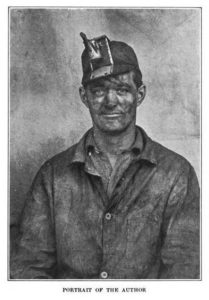

Seventy Years in the Coal Mine

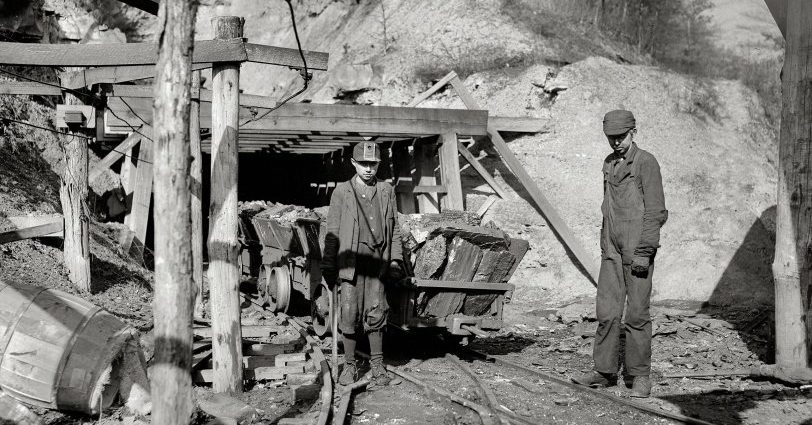

**Featured Image:

Photo: On the tipple of Cross Mountain Mine, near Coal Creek, Tennessee, December 1910.

Photo by Lewis Wickes Hine for the National Child Labor Committee

Source: https://www.shorpy.com/node/15872

References

| ↑1 | Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 10). Two Hundred Lives Snuffed Out in East Tenn. Mine Disaster. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑9, ↑10, ↑12 | Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 10). Briceville Mine Inspected Twice in Four Months. |

| ↑3 | Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1912, Apr 19). Chief Inspector Reports on the Briceville Mine. pg 14 |

| ↑4 | Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 12). Five Entombed Men in the Cross Mountain Mine are Found Alive. pg 10 |

| ↑5, ↑7, ↑8, ↑28, ↑29 | Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1912, Apr 19). Chief Inspector Reports on the Briceville Mine. |

| ↑6, ↑11, ↑13 | The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 10). Hardly One Ray of Hope for 207 Men Entombed in The Tennessee Mine. |

| ↑14 | The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 10). Hardly One Ray of Hope for 207 Men Entombed in The Tennessee Mine. pg 2 |

| ↑15 | Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 10). Two Hundred Lives Snuffed Out in East Tenn. Mine Disaster. pg 8 |

| ↑16 | The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 10). Women and Children Wailing at Mouth of Ill-Fated Mine; No Hope for Entombed Miners. p. 2 C. |

| ↑17, ↑18, ↑26 | Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 11). Eight Bodies Taken from Ill-Fated Mine; No Hope of Rescue. pg 7 |

| ↑19 | The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 11). All Dead. |

| ↑20 | Popular Mechanics. (1912, Mar). Canary Birds in Mine-Rescue Work. p. 355. Retrieved from here |

| ↑21, ↑22 | Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 14). Forty-Nine Men Entombed in Mine Brought Out Dead. |

| ↑23, ↑24 | The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 12). Thought Dead, Buried Miners Are Found Alive. |

| ↑25 | The Atlanta Constitution. (1911, Dec 12). Thought Dead, Buried Miners Are Found Alive. pg 13 |

| ↑27 | Nashville Tennessean and The Nashville American. (1911, Dec 14). Forty-Nine Men Entombed in Mine Brought Out Dead. pg 2 |

A very harrowing and heartbreaking series, especially poignant given your family connection. Despite my roots in Tennessee, I had never heard of these disasters. Thank you for a much needed history lesson.

Hello Jim. I was very glad to bring these happenings to light. I was told these stories when I was a little girl. Initially, I wanted to write about the Coal Creek War. Then, when I saw Fraterville took place a mere ten years later, and Cross Mountain almost ten years after that, I considered telling it in three parts. So many of my family members worked in the mines and lived in coal camps. I kept my ears open to their experiences. One never forgets certain tales.

A wonderful combination of historical information, memoir, and storytelling. I am looking forward to more journeys with you.

Thank you, Peg. I am delighted to bring you along!