Growing up in the shadow of Lookout Mountain in Chattanooga, Tennessee, a city socially stratified according to altitude, I fell under the spell of native author Christine Noble Govan, whose specialty was children’s mystery novels set in or near the city’s scenic attractions. A prolific writer of more than 50 novels, Govan occupied two entire shelves at my elementary school library, showcasing such titles as The Mystery of Moccasin Bend (1957), The Mystery at Plum Nelly (1959), and The Mystery at Rock City (1960). The only drawback to having so many of her books in the library was that I could only check out one at a time. That fact forced me to devour them. I even convinced myself, for a time, that I alone was Christine Govan’s target audience and that she wrote the mysteries exclusively for me. I was beginning to understand the impact a writer can have on a reader eager to suspend disbelief in service to a compelling story and a gifted storyteller.

It wasn’t just the familiar place names, either. I happily identified and saw myself as a member of a coed club of young sleuths known as the Lookouts. Their specialty was solving crimes committed by adults. The kids were smart, savvy, and persistent. Their personalities were unique and engaging. Govan could never be accused of creating cardboard cut-out characters. They were, by turns, bored, irascible, curious, and excited. They never expected adults to entertain them and would have found the idea anathema. More than anything, I wanted to be part of their gang. I refused to believe they were fictional characters.

In 1964, I encountered my literary idol face to face for the first time. The occasion was the annual Plum Nelly Clothesline Art Show which first occurred in 1947. To this day, Plum Nelly sells the wares of local, regional, and occasional worldwide artists during a single October weekend. Plum Nelly got its name when its founder, Fannie Mennen, hosted the event on her property at Lookout Mountain. In Southern parlance, Mennen’s brother-in-law declared, “Your place is plum out of Tennessee and nelly [nearly] out of Georgia.” The name stuck.

My eleven-year-old self stood in line with other kids for Mrs. Govan to sign our books. I’d bought mine – The Mystery at Rock City – from the Scholastic Book Services available for order at school. Christine Govan was warm and gracious to the children filing by. Her smile never flagged and shone as bright as the sun on that crisp October Saturday. I submitted my book shyly and she responded generously by thanking me for being one of her young readers. Her filigreed signature was the art of a bygone era.

The next time I encountered Mrs. Govan was as a junior in college. In the intervening years, I’d acquired some information about my literary heroine. I discovered that, although born in New York in 1898, she lived most of her life in Chattanooga. Her father, Stephen E. Noble, died when Christine was four years old, prompting the family to move to Sewanee, Tennessee, because her maternal great-uncle Charles Todd Quintard lived there. After several years, the family moved back to Chattanooga where Govan (née Noble) completed high school.

Afterwards, the future author enrolled as a scholarship student at the University of Chattanooga but left because her family needed her financial support. Certified to teach first grade, Christine Govan taught briefly at a rural one-room school. In June 1918 she married Gilbert E. Govan, a bookstore owner, originally from Atlanta. They had three children: Emmy, Mary, and James. Despite her domestic responsibilities, Govan’s approach to her work was deliberate and calculated. She vowed to publish two books each year.

One particularly interesting factoid about Govan’s life was her decision to become an early member of the NAACP and to support the civil rights movement in the largely Jim Crow South. Her best-selling trilogy Those Plummer Children focused on interracial friendships. Editions were published in England, Denmark, Germany, Japan, and Sweden.

I met Mrs. Govan for a second time when I was twenty. She was seventy-five. A mutual acquaintance introduced her and my father. When my dad said what a fan of her work I was, and that I was majoring in English in college, and that I aspired to be a writer, Govan extended an invitation for me to visit her on the mountain. My father arranged a meeting during Christmas break.

I was filled with dread that escalated into full-blown terror. What twenty-year-old aspiring to be a writer doesn’t harbor a suspicion that he or she is a fraud? Mrs. Govan would see through my façade. It’s one thing, I told myself, to want to be a writer; it’s another thing to write and see one’s work published between covers. Despite being three-quarters of a century old, Christine Noble Govan was hard at work writing novels. She’d just published Danger Downriver (1973) at the time I visited her.

She entertained me with all the graciousness and hospitality I should have expected. My jitters melted in a matter of minutes. She asked me about my favorite authors. I confided that a course in Shakespeare had ruined me for vocations in medicine or law. I wanted to write and to teach the works of other writers – like Shakespeare. I’d done most of the talking, but at this point she offered the only piece of writerly advice I was to receive: “Always measure yourself by the best, and you’ll never be disappointed.” When I groused that words sometimes failed me or that I lacked inspiration for stories, she spoke up gently: “Can you recall a day of childhood in stark clarity?” I nodded that I could. “Then you’ll never lack for material.”

For the better part of an hour, I bent Mrs. Govan’s ear. Years later, when reflecting on the kindness she afforded me that day, I recalled a maxim attributed to St. Francis of Assissi: “The first duty of loving is listening.” Christine Noble Govan loved her literary landscape, loved the characters who inhabited it, and loved the real-life boys and girls transformed by the exploits of the Lookouts. If she were here for another hour, I’d thank her that some small measure of the grit, boldness, and generosity of spirit demonstrated by her child sleuths had rubbed off on me. If there’s a better way to sing an author’s praises, I don’t know it.

![]()

Enjoy the following excerpt from Number 5 Hackberry Street by Christine Noble Govan (pgs. 83-85):

In her room Tilly, having given the dining room a lick and a promise, was skittering around the bed like a water spider, yanking up the sheets, slamming the pillows into place, and jerking at the spread. Delta tried to help from the opposite side but she couldn’t keep up with Tilly, who stuffed a pair of worn slippers under the bed and her nightgown under the pillow and said, “Now. What have you got on your mind? Have you found out how to get rid of ’em?” she wagged her head toward the cottage back of the house.

“Come out in the swing,” said Delta, “and I’ll show you something. I hid it out there when I came in.”

Burning with curiosity, Tilly ran out into the hall and across the big porch. The sun was hot and the thick grass warm under their feet. On the slope of the yard, Papa had spaded up a place to plant late beans and squash and the smell of the fresh-turned earth came to them as they hurried to the swing.

Delta reached under the swing and from a patch of thick clover took an odd, ugly little doll made of red clay.

“We’re goin’ to voodoo ’em!” she said in a hoarse whisper.

“Voodoo who?” asked Tilly and giggled.

“Shut up, dummy! They’ll hear you,” cried Delta glancing toward the hedge. “See, I made this figure – it’s one of the witches. We’ll have to decide which one. We’ll stick pins in it – that’s what they do in Africa where they voodoo people – and then something dreadful will happen to her – the witch.”

“Golly! Let’s make it the little dumpy one. This figure’s sorter dumpy,” said Tilly taking the grotesque doll in her hands. “She’s the one all the time stirrin’ up brews in that pot. Let’s stick pins in her!”

“All right. But you’ll have to get the pins. I couldn’t find any at home. Go get ’em now.”

Tilly was back in a moment with a card full of new pins. “Where’ll we stick ’em?” she asked excitedly.

“Right in the heart!” said Delta, taking a pin and poising it.

“Wait! We don’t want to kill anybody!” cried Tilly suddenly frightened. “We just want to make ’em stop being witches. Maybe we just ought to stick ’em in the head so she can’t think and can’t remember her wicked charms.”

“Oh, all right,” said Delta reluctantly. “But let’s put plenty of ’em in. My father told me you think and feel with different parts of your brain. We sure don’t want to miss the parts she thinks up her evil spells with.”

Presently the clay figure wore a sort of prickly pear of a hat. Bright new pins stuck up all over its head.

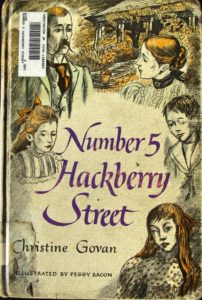

**Featured Image: Something About the Author: Facts and Pictures about Contemporary Authors and Illustrators of Books for Young People, Vol. 9, by Anne Commire (1976), p. 81-83

A touching, heartwarming story. Your detailed, descriptive memories from your early years are remarkable. I can just vaguely recall reading The Mystery at Rock City and the thrill that it featured a local landmark.

I’m pretty sure I read all of her books that were in the Normal Park library. Thanks for the memories Eddie.

Thank you for this peak into one of your youthful inspirations Ed! These sound like wonderful books right up my alley. I love mysteries and adventure stories and I clearly need to put these books at the top of my “to read” pile! Despite my youth being far behind me, I still thoroughly enjoy reading well done YA literature and Mrs. Govan couldn’t come with a higher recommendation!

Thank you for this informative article and details of your firsthand encounters with her. I grew up in the ’80s but similarly enjoy well-written YA mystery/horror fiction, particularly those written prior to 1980. If you know where I can purchase some of her ‘Lookout’ books as a relatively inexpensive lot, please send a message. I just discovered this series and have only two.