Tomorrow is the birthday of revered Appalachian poet and novelist Byron Herbert Reece (1917-1958). Join Appalachia Bare in celebrating his life and talent through a heartfelt tribute by acclaimed writer, Mark Wallace Maguire.

I go by ways of rust and flame

Beneath the bent and lonely sky;

Behind me on the ways I came

I see the hedges lying bare,

But neither question nor reply.

from “I Go By Ways of Rust and Flame” by Byron Herbert Reece.

I imagine Reece scribbling these words on a tattered notepad, sweat trickling down his arms as he takes a break from plowing a field under the frown of the North Georgia mountains. Dubbed a farmer-poet, Reece split his life between poetic pursuits and tending the land. Wood block carvings capture him leaning on a plow with a notepad in hand.

Reece led a life filled with paradox from chance and circumstance. He was both thrilled and inspired by nature and yet, in many ways, imprisoned by it. While his gifts gave him the avenue to achieve wider success, it was the land that kept him tethered to the valleys and mountains of north Georgia, a life he could never truly abandon.

Reece’s gift for writing was born from his immersion in the traditional folks songs and stories shared by his family and community. Expressing his thoughts and ideas through reading and writing were innate to his character. He devoured the Bible, especially, the Old Testament. And he read voraciously with one account of him reading for a solid 16 hours while holed up inside his family’s cabin during a snowstorm.

While he sharpened his intellect and crafted well-honed poetry that earned him local praise, he could never quite escape the responsibilities of the family farm and embrace a completely literary life. His pursuit of higher education at Young Harris College was filled with starts and stops. The frequent stops were not born from a Whitman-esque desire to, ‘loaf or indulge in pleasure,’ but because the farm and his family needed him. The dirt would not turn itself and the seeds would not be planted by hope. There was work to be done.

Reece would have to turn his hand from pen to plow many times throughout his life. The need to keep up the farm (poetry never did pay the bills), the need to care for his aging and ailing parents were chains that would always hinder him.

A lesser man might have discarded writing. It is a painful thing to be teased by the potential of a dream. But, nonetheless, with his boots entrenched in the soil, his eyes dimmed by the shadow of Blood Mountain, and his arms fixed to the plough, Reece did not desist writing. In fact, he only wrote more. And through time and serendipity, he grew an audience.

During what critics roughly dub as his “ten year period,” Reece was extremely successful. He was awarded two Guggenheims, nominated for a Pulitzer, and had multiple books of poetry and prose published.

Newsweek wrote an impressive spread on him and he gained esteemed status as a writer-in-residence at UCLA, Young Harris, and Emory.

Yet, the farm and family kept tugging him back. In the early 1950s, his father and mother both grew so ill at times, that Reece had to return home. At one point he was stricken with the same tuberculosis that ailed his mother forcing him to spend time in a sanitarium in the northwest foothills of Rome, Georgia. After a brief respite he left of his own will and returned home.

Back to the farm.

Reece suffered with depression throughout most of his life and there are certainly tones of darkness in his poetry.

But, even with the darkness that seeps through his works, he is not a despondent poet. You will not find him wading in the waters of self-pity. As with the excerpt from the poem at the top of this piece, he remained observant, philosophical and hopeful despite the time of year. In the poem, “Two Men in Me,” he addresses the temporal nature of life.

Two Men in Me

A stone is stone but I am soul and matter;

Unfathomed spirit and enduring bone

Clothed both with flesh which death in dust will scatter

When from the partnership the soul is gone.

Good servants and obedient to my will

Are these my trunk and limbs the nerves enmesh,

And while the soul keeps there its dwelling still

It takes its orders of the temporal flesh.Two men in me race forth and which shall win

I do not know, nor what the victory,

Nor shall I know until the two go hence

And what I learn I cannot publish then

For he of me who spoke must silent be

When death betrays me to my elements.

When I read his poems, I feel a common kinship. Reece in many ways walked alone. He had a small group of friends and advocates for his work, but he never married. And, he never crested that huge wave of poetic success that landed him at the forefront of the literary community.

In addition to farming, Reece spent part of his final years teaching at Young Harris College in spite of the fact that he never officially graduated. He remained a man of two worlds. The hallowed halls of academia. The furrowed dirt rows of seed and sweat and sustenance.

Throughout his work his verse remained clean, accessible, clever and well-crafted. His legacy might have taken a greater hold if he had been born in a different time or place. Dr. Ruth B. Looper, who serves as English Professor at Young Harris College, noted:

“If Reece had been born a generation earlier, he might have garnered more attention as a Pre-War or even as a WWI poet (if he had enlisted) because formal poetry was still held in high regard,” she said. “Literary Modernism with its focus on fragmentation and alienation did not dominate until after the bloody horrors of WWI. If Reece were born right before or after WWII, it’s also possible that his verse would have attracted more attention. The New Formalism movement in the U.S. during the 1980s, 90s, and early 2000s could have been a home for him.”

Perhaps if Reece had lived during a time when he could indulge his creativity he might have thrived mentally as well. As it is, he took his own life at the age of 40.

In spite of his truncated time on this earth, he leaves behind an impressive legacy that has lurked on the edges of Georgia’s cultural consciousness for years.

Revisiting Reece’s work in the present day is refreshing. It is clean, well said and succinct. There is no deliberate abstraction and no overt gushing so common from confessional poets. It remains simple, curious and viscerally layered with introspection and philosophy.

While Reece has lurked on the edges of Georgia’s cultural consciousness for years, there is hope for a stronger revival. In 2003, the Byron Herbert Reece Society was formed. Shortly thereafter, the Reece family farm was acquired by Union County and leased to the society. The society created a museum and interpretive center that celebrates the poet’s work.

“I’m convinced, however, that his legacy will be enlarged over the next generation as more teachers, students, and general readers see his work as environmentally and socially aware,” said Dr. Looper. “Much of his poetry commemorates the beauty of the Appalachian mountains, and his novels offer astute commentary on the racial and economic divides of the region. Last, Appalachian Studies is a growing field, and my hope is that Reece will join the expanding canon of Appalachian writers worth teaching.”

As Reece wrote in his poem, “The Reach of Song”:

From chips and shards in idle times,

I made these stories, shaped these rhymes;

May they engage some friendly tongue

When I am past the reach of song.

And, truly his words continue to reach into this century and hopefully many more to come.

![]()

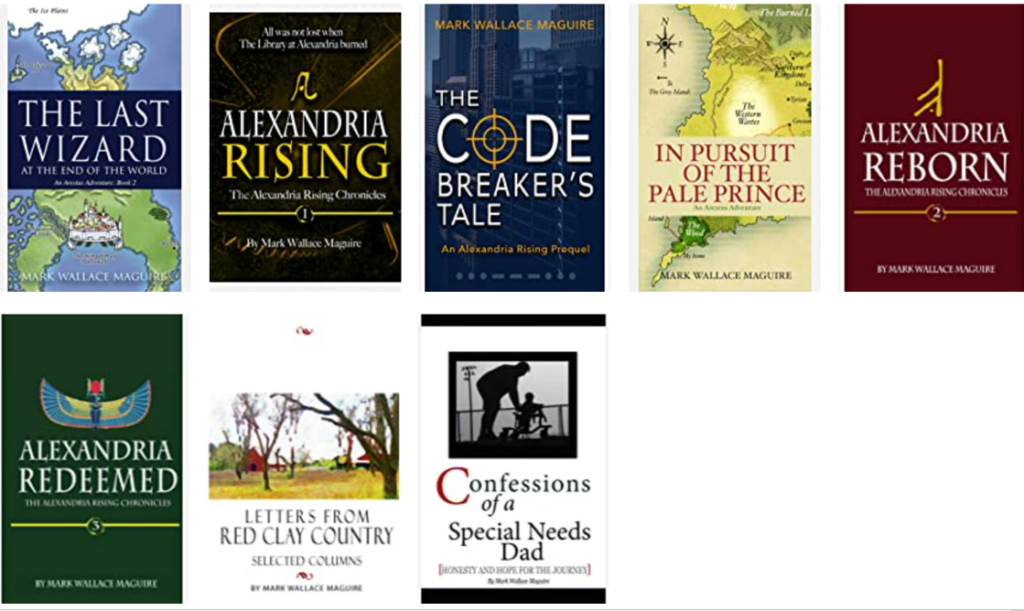

Mark Wallace Maguire is the author of eight books of fiction and nonfiction, including the Kindle best-seller, Alexandria Rising. He is also an award-winning journalist, columnist, and poet whose work has appeared in over 60 magazines, news sites, and literary reviews. He has received more than 20 awards from organizations including The Associated Press and Society of Professional Journalists. Maguire serves on the Advisory Board of the global nonprofit Children’s Literature for Children, and is a member of The Georgia Poetry Society and the Presbyterian Network of Communicators. A man without a hometown, Maguire has lived in over 15 cities throughout the South and now lives in Fayette County, Georgia, with his family.

Click on the collective image of Maguire’s books below to find out where to purchase them:

FOR FURTHER READING AND INFORMATION ABOUT BYRON HERBERT REECE, VISIT:

- Mountain Singer: The Life and the Legacy of Byron Herbert Reece by Raymond Cook.

- Byron Herbert Reece Society

**Featured image of Byron Herbert Reece shucking corn from The Reach of Song – An Appalachian Drama – 1992 theatre program – Internet Archive – altered, cropped to fit

Happy Birthday, Byron. I am happy to meet you through your recorded words and added a visit to your home on my Spring calendar.