I hope you enjoy this fourth installment of Appalachians in Moving Pictures. My initial hope was to fit all the actors, featured and honorable, in this post. However, the information on these actors far exceeded my expectations. So, I have decided to include a Part IV-B for honorable mentions that will post soon.

Dick Gilbert

Dick Gilbert was born Richard Lewis Gilbert in Knox County, Kentucky on July 12, 1889. He was a Light Heavyweight boxer nicknamed “Fighting Dick” whose profile indicates he had more losses than wins and draws put together. He purportedly once fought Jack Dempsey but lost after ten rounds.

Gilbert quit boxing and began an acting career instead. His silent film roles included many small parts like police officers, various drivers, tough guys, henchmen, etc. His debut film was Young Sherlocks (1922), an Our Gang short, where he played the (uncredited) role of “Motorist and Kidnapper.” He transitioned into talking pictures playing these same extra-type roles.

He was married once, to Anna Mahoney, and they remained together until he died of heart failure on May 6, 1960 in Goldfield, Nevada.

![]()

![]()

Charles Hutchison

Charles A. Hutchison, nicknamed “Hurricane Hutch,” was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on December 3, 1879. He attended Western University.

He had a successful career on Broadway and vaudeville before he entered film. His first moving picture role was Preston in The Fatal Portrait (1914). He became an actor who chiefly played in the silent action genre.

He was considered the “king of action serials . . . famous for his trick motorcycle jumps.” He also wrote scenes – “hair raising” scenes with dangerous stunts – and directed (according to IMDB) around thirty-three films as well. He kept himself fit through “strenuous gymnastic exercise.”

He married Edith Thornton. He died May 30, 1949 in Hollywood, California.

![]()

![]()

Arthur Lake

Arthur Lake was born Arthur William Silverlake in Corbin, Kentucky on April 17, 1905.

When he was around three years old, he worked with his parents in their acrobatic circus act, “The Flying Silverlakes.” The Silverlakes moved to California and took their skills to vaudeville.

The California move gave Arthur an opportunity to work in movies. He appeared as “one of the ‘Fox Kiddies’ in a series of silent-film . . . fairy tales.” His first film was Jack and the Beanstalk (1917). He later played in westerns as adolescent characters or in comedies as teenage “dimwitted youngsters.” While working for Universal Pictures, the production company changed his name to “Lake” because “Silverlake sounded too Jewish.” He is best remembered in his adult role as “Dagwood Bumstead” in the Blondie series, on radio and film.

One surprising fact about Lake is his connection to the infamous Black Dahlia case. Authorities working the case questioned Arthur Lake about the murder of Elizabeth Short. (I’m assuming these were local authorities. The FBI Vault files on the case don’t mention Lake, though I admit I skimmed through the documents. Plus, Arthur Lake was really close to William Randolph Hearst, who was a powerful enough newspaper man to silence the information.) Lake had “met Short when she was volunteering at the Hollywood Canteen.” He was released without charges.

Lake was a clever businessman who invested wisely and increased his fortune. He married Patricia Van Cleve Lake (many other sources spell her maiden name Van Cleeve) and they remained together for fifty years (1937-1987), until his death.

Arthur Lake met his wife at Marion Davies‘ house. Several sources say Patricia may have been the secret love child of William Randolph Hearst and Davies, who had a very visible love affair. Initially, it was believed that Patricia was the daughter of Davies’ sister and her husband, George Van Cleeve. Before her death, however, Patricia reportedly told her son that she was the child of the Hearst-Davies affair.

Arthur Lake died of a heart attack about six years before his wife on January 9, 1987 in Indian Wells, California.

![]()

![]()

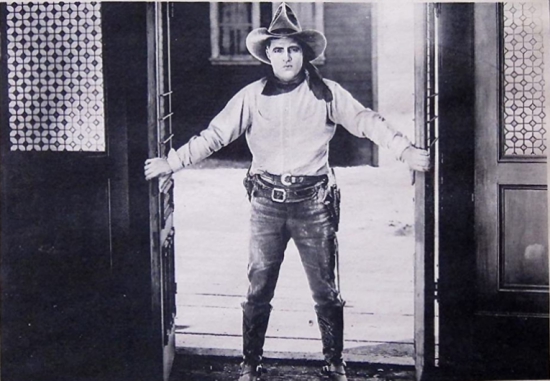

Rex Lease

He was born Rex Lloyd Lease in Central City (Huntington), West Virginia on February 11, 1903. He initially wanted to be a minister.

From the time of his first movie playing an adult son in A Woman Who Sinned (1924), Lease acted in drama and action roles. In the late 20s, he began a long career in the western genre. From all the sources I’ve read, he was one of those actors who straddled a point in time – on one side was a blooming stardom and on the other side were Western up-and-comers, Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. As a result, Lease acted in mostly B-movies or as second billing. Still, he has a very extensive filmography of almost three-hundred movies.

His behavior was infamous. He had a bad temper and his outbursts affected his relationships, primarily with women. He often had brawls with various Hollywood actors. And he had no qualms fighting with women, either. In 1930, he punched dancer Vivian Duncan in the face, giving her a black eye. He was subsequently arrested, pled guilty, and paid a fifty dollar fine. I’m guessing that “punishment” didn’t set too well with the dancer’s brother, Harold Duncan, because later that year, he exacted revenge and beat the crap out of Lease. According to the website, “The Old Corral,” newspapers reported on the event with headlines like, “Duncan Avenges Sister’s Beating,” and articles stating Duncan was “soundly beating the motion picture actor in a hotel café.”

Lease wasn’t necessarily safe from himself, either. In 1936, he attempted suicide by cutting his wrist, “despondent because he had been out of work for some time and because his third wife, Elsa, divorced him.”

In fact, Lease was married five times, to Charlotte Merriam, Eleanor Hunt, Elsa Roberts, Isabelle Richle, and Helen Ince. All his marriages ended in divorce, though his longest marriage was just shy of twenty years with Richle.

He did eventually settle down some. In 1939, he and actor Kenneth Harlan published a cookbook, What Actors Eat When They Eat. He continued to act and “became a steady, dependable” character actor. In his last job he played a variety of characters on the television series, The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp (1955-1961).

Rex Lease died January 3, 1966 in Van Nuys, California.

![]()

![]()

Thomas Meighan

Thomas Meighan was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on April 9, 1879.

He initially attended St. Mary’s College to pursue a career in medicine but soon switched to theatre.

He had a very successful run on Broadway, but he left the stage when he was thirty-six years old to pursue acting in moving pictures. He was one of Cecil B. DeMille’s favorite actors. Meighan steadily climbed the Hollywood rungs and achieved leading male roles.

Interestingly, Meighan was “the only attendee and witness at the secret marriage of Olive Thomas and Jack Pickford.” (Check out Part II of this series to see more about Olive Thomas’s story.)

The Richey Amusement Company in New Port Richey, Florida built the Thomas Meighan Theatre to honor the actor. The building’s name has now changed to Richey Suncoast Theatre and is currently a community playhouse.

Meighan was married once to Francis Ring and they stayed together until his death.

Thomas Meighan died on July 8, 1936 in Long Island, New York. IMDB lists his cause of death as cancer. However, in the July 18, 1936 edition of the magazine Motion Picture Herald (and on his Find-A-Grave biography), his cause of death is listed as pneumonia. The magazine states he was “stricken with pneumonia in Hollywood in January 1935 and the illness left a bronchial tube obstruction.” He seemed to recover after some time “but a relapse followed” and he passed away.

![]()

![]()

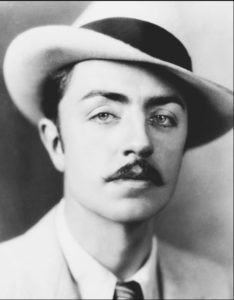

Adolphe Menjou

Adolphe was born Adolphe Jean Menjou in Pittsburth, Pennsylvania on February 18, 1890. His mother was James Joyce’s cousin. His father was adamantly against Menjou acting so he sent him to Culver Military Academy, hoping his son would seek an engineering degree. Thereafter, Menjou was enrolled at Stiles University, then Cornell University. Menjou “abruptly changed his major to liberal arts and began auditioning for college plays.” His brother, Henri Menjou, was also an actor.

He moved to New York to pursue theatre, but it was a rocky start. He worked as a day laborer for a time, a “haberdasher,” and waiter. During these jobs, he also performed a little in vaudeville. He never achieved a career in stage acting, but began working in film until World War I broke out and “he served as a captain with the Ambulance Corps in France.”

He finally broke into serious moving pictures in 1921, playing the role of Dr. Littlefield in The Faith Healer.

When the stock market crashed, Paramount terminated his contract, and “his status as leading man ended.” He did see good success in the thirties, though, and was nominated for an Oscar for “Best Actor” as Walter Burns in The Front Page (1931).

Menjou was known for the signature mustache he kept until the 1950s. He was described as “suave,” and “debonair,” a man with “continental charm” and “sartorial opulence.” He was quite the dandy, winning “the nation’s ‘best dressed man’ nine times.” He was highly intelligent and mastered six different languages.

The outside of the man was very different from the inside. His ideology, his opinions, and convictions were destructive during the McCarthy era, and his “extreme hardcore . . . poltics” made him unpopular. He participated “as a ‘friendly witness’” with the House Un-American Activities Commission [HUAC]. Menjou used his Hollywood status to help the commision become more palatable and believable to the public. He named names during his testimony, and told the HUAC: “Hollywood is one of the main centers of Communist activity in America.”

Menjou “was well-known for his ultra-right-wing political stances. He once said that all Communists should be taken out and shot, regardless of whether they were American citizens or not.” He was also a member of the John Birch Society. His political leanings, however, were based on personal finances and the economy. He thought “the Democratic party would try to take his money and destroy the value of a dollar.”

He also joined Walt Disney and formed the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals in 1944. According to The Inquisition in Hollywood: Politics in the Film Community, 1930-1960 (1980, Anchor Press) by joint authors, Larry Ceplair and Steven Englund, the organization was “militantly anti-Communist.” (p. 193)

Menjou was married three times to Katherine Conn Tinsley, Kathryn Carver, and Verree Teasdale (until his death).

Adolphe Menjou died of hepatitis on October 29, 1963 in Beverly Hills, California. His estate was valued at almost one million dollars.

![]()

![]()

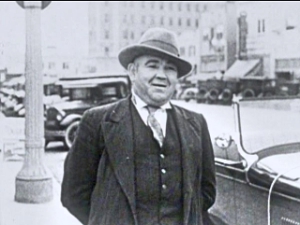

Tom Mix

Tom Mix was born Thomas Hezikiah (other spelling: Hezekiah) Mix in Mix Run, Pennsylvania on January 6, 1880. He didn’t like his middle name and eventually changed it to Edwin, his father’s name. His father worked as a lumberman so the family lived in a logging camp. Mix learned to ride horses from his father.

Mix had a variety of pretty fascinating occupations throughout his life before he became an actor. When he was young, he worked odd-jobs, one of which was as “a waterboy for lumberjacks.” He was an artillery sergeant during the Philippine-American War (1899-1902) and spent that military period in the “continental U.S. Tom ended his enlistment by simple desertion,” a fact unknown until he died. This bit of information might explain why all the sources I found suggested he didn’t like to talk about his military service. Mix once worked as a bartender for the Blue Belle Saloon. He was also sheriff (more like a sheriff’s deputy or a “night marshal”) of Dewey, Oklahoma in 1904. He was a horse wrangler and bronco buster in several Wild West shows. One of those shows furnished Selig pictures with various cowboys, “Indians,” or horses. Tom Mix was one of the men sent to Selig with horses for the movie Ranch Life in the Great Southwest (1910). He’s listed as a “bronco buster” in the film. (Another source lists his first film as the short film “The Cowboy Millionaire” (1909), also by Selig.) After he became popular, he wrote several articles for various movie magazines, detailing pieces of his life or how he made his success. Take a gander at some of these on Virtual History‘s Tom Mix site.

He acted in over eighty short films until he signed a contract with Fox in 1917 and performed in his first (according to IMDB filmography) full feature film, Cupid’s Roundup (1918). He became one of the most popular cowboy stars in silent film. He made over 300 films, including nine talking pictures and a “15 chapter serial, The Miracle Rider (1935). Many of these shorts and movies are “lost films.” They “burned in a studio fire.”

Mix didn’t make a good transition into sound. One reason could have been because he was distracted. He “suffered many injuries as well as financial losses due to the Stock Market Crash and Depression, law suits, back taxes [probably because of his accountant],” etc. His injuries arose because he did his own stunts, “sharpshooting with live ammunition, knife-throwing or stunt-riding.” He made over six million dollars in his lifetime but he lived extravagantly, “throwing lavish parties, arriving at others’ parties in full western regalia, and amassing an enormous collection of cowboy boots and hats,” and he lost much of it by the end of his life.

He left motion pictures in 1935. He toured the circus circuit and even had his own, “the Tom Mix Circus from 1936-1938.”

He was married five times: Grace I. Allen, Jewel “Kitty” Perrine, Olive Mix, Victoria Forde, and Mabel Hubbell Ward (until his death).

Tom Mix died in an automobile accident on October 12, 1940 in Florence, Arizona. But others were determined not to forget him. In the 1940s, a radio show called “The Tom Mix Show” aired with various actors reading Mix’s part. This show transitioned onto television in the 1950s and showcased the actor’s old movies. The Tom Mix Museum was built in 1965 in Dewey, Oklahoma and houses much of his memorabilia. A stream in Pinal County, Arizona was named after the star, Tom Mix Wash.

One other tidbit of information about Tom Mix – he was a pallbearer at Wyatt Earp’s funeral in January 1929. Earp was somewhat of an advisor on Hollywood’s Westerns and used the opportunity to “tell flamboyant matinee idols like William Hart and Tom Mix how it had really been.” Mix “wept openly” at Earp’s funeral.

![]()

![]()

William Powell

William Powell was born William Horatio Powell in Pittsburth, Pennsylvania on July 29, 1892

His father was an accountant who wanted his son to pursue a law degree. Powell enrolled at the University of Kansas and made a small attempt to do so, but he wanted to act. He quit the university and asked his monied aunt to help him out financially until he could get on his feet. And (thankfully) she did.

He performed on stage in New York and in vaudeville for ten years before acting in films. Paramount Pictures was the first production company to sign Powell. From 1922 until 1928, he acted in over thirty silent films.

Powell bloomed as an actor at the end of the silent era and his career catapulted during talking pictures, particularly after The Canary Murder Case (1929), where he played Philo Vance. He was a very versatile actor, playing in comedies, thrillers, dramas, etc.

He received three academy award nominations: the first for The Thin Man (1934), the second for My Man Godfrey (1936), and the third for Life with Father (1947). Incidentally, he and Myrna Loy, counting the Thin Man “series,” acted in fourteen films together.

He was married three times: Eileen Wilson, Carole Lombard, Diana Lewis (until his death). He was also engaged to Jean Harlow (giving her a 150-carat sapphire engagement ring) until she died suddenly in 1937 of “uremic poisoning brought on by acute nephritis.” The pair met on the set of Reckless (1935). He was devastated and stopped acting for a while.

Not too many years later, around 1938, Powell was diagnosed with cancer but he and his agent kept it secret. He chose an “experimental treatment where platinum needles containing radium pellets were inserted” throughout his body for six months, and his cancer went into remission. He took some time away from acting under the guise of an “eye injury” and “a routine abdominal operation.”

In 1944, Powell and other actors and actresses received death threats from the American First Committee (AFC) – an anti-semitic, fascist group against American involvement in WWII. The FBI investigated the letters. One letter read:

WILLIAM POWELL

If you value your life you will send $10,000 to American First Committee . . . I urge you not to call for F.B.I. or you will die suddenly. We are all over the United States.

(Mark as signature)

The AFC disbanded (at least as a larger organization which at one time had over 800,000 members) in 1941. I’m guessing the letter was sent by the group’s remnants, or, perhaps they still had numbers but had less power and influence after the United States joined the war.

Powell retired from acting after making Mister Roberts (1955). He couldn’t remember his lines, a highly unusual occurrence for him, and the reason was mostly due to health reasons – “bouts with cancer,” etc. From the movie’s still photos, it seems evident (to me, at least) Powell is tired, worn down, and unwell.

Powell suffered more tragedy almost thirty years after Harlow’s death when his son, William Powell, Jr., who had depression and several serious illnesses, committed suicide in March 1968 by repeatedly stabbing himself in the upper torso in the shower. He left a long suicide note to his father, with whom he was very close.

William Powell died on March 5, 1984 in Palm Springs, California. IMDB lists the cause of death as a heart attack. Find-A-Grave, however lists the cause as “simply of old age at 91.”

![]()

![]()

Larry Semon

Larry Semon was born in West Point, Mississippi on July 16, 1889. His nickname was Ridolini and he was a “slapstick comedian” known for his cutesy “clownish smile.”

His father was traveling magician, Zera the Great. His act involved the whole family and Larry was “trained in stage comedy and acrobatics” at an early age. He was a good “pantomime,” which really came in handy for motion picture comedies. The family lived on the edge of abject poverty because most all their money went into Zera the Great’s act. They often had no home and slept on benches. His father died when Larry was thirteen years old. Before he died, he told his son to leave the family business and get an education.

Semon did just what his father suggested. He became a cartoonist and worked for several New York City newspapers, like The Brooklyn Eagle. His first work , though, was for The Philadelphia North American.

He worked as a cartoon artist until around 1914, when New York Vitagraph Studios noticed his jocular wit and hired him as “a gag writer” in 1915. Semon soon directed the Hughie Mack comedy shorts and secured the leading role after the star left.

Audiences and studios at the time thought Semon was funnier than Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton. The only comedian Semon couldn’t touch was Charlie Chaplin, who “was a god” in the comedic world. Semon made marginally less money than Chaplin. And Buster Keaton never saw the amount of money Semon made: a three-year contract, for example, with Vitagraph for $3,600,000.

Semon “produced as well as wrote, starred in and directed his own films.” The shorts were exciting and fast-paced, with action and endlessly delightful gags (delightful, at least, at the beginning of Semon’s career).

He hired Stan Laurel and the two became a comedy duo until Laurel abruptly left. One reason might have been because the year was 1918, when the influenza pandemic broke out. Public areas were forced to close until the government deemed them safe. Vitagraph was one of those places. When the studio reopened, Laurel had already returned to vaudeville because he needed money. Oliver Hardy also joined Semon and stayed as “a prominent member.”

Semon spent a lot of money to make his films. Though the money he made seems surprisingly high, the fact is Semon and other comedians at that time had to foot the bill for their own films up to a certain point, then the production company (if that was the terms of the contract) picked up the extra film expenses. Semon’s extravagant sets and costumes were costly, and Vitagraph didn’t want to pay their part because they thought Semon purposely overspent. So, lawsuits ensued. At one point, Vitagraph sued the actor for over $400,000 – a record at the time. When all was said and done, Semon had won (in a way). Vitagraph drew up a new contract, giving him more control over his productions. But this decision turned out to be disastrous for both parties. Semon wasn’t equipped to deal with finances in general, let alone be solely responsible for them. He parted ways with Vitagraph in 1923 and the company went under about a year later.

Viewers grew tired of Semon’s films because the humor was the same old, monotonous, absurd farce. Semon decided the time was right to venture into his movie-making dream: A film version of Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1925). He joined Chadwick Pictures and took charge of filming. The movie was a flop. Critics and movie-goers found it to be a “disastrous” version of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz ( Frank Baum, 1925). Although the movie had a great cast, it was “a trite and inept run-of-the-mill comedy.”

Semon spiraled down hard and fast after this failure, and the trajectory was a pitiful reversal witnessed by everyone. Semon searched for whatever acting work he could find to “stave off creditors.” Then, Chadwick Pictures went under and Semon went back to work writing gag scenes. His luck worsened with added failures so he came almost full circle, back to vaudeville. He and his wife, Dorothy Dwan, “lost everything.” She moved in with her mother while Semon “worked the two and three-a day vaudeville acts during that 1928 summer.”

He contracted tuberculosis in 1928, and, in the same year, he had a mental breakdown, and “entered a sanitarium . . . where he reportedly died on October 8,” 1928 of “lobar pneumonia.”

Rumors swirled about the truthfulness of his death.

The following interview (snippets) with Semon’s wife (second marriage, Dorothy Dwan) does cause one to question:

“I was wired that he had been taken ill and was going to Victorville, and you know what that meant.” Victorville specialized in tuberculosis. She continues narrating,

“Larry was being handled by these two guys. I don’t know who they were. But they wouldn’t allow me to see Larry. They told me I had to stay away from him until he was better. They wouldn’t let me see him at all.” Semon’s doctor was Harry S. Garceion. She received a call about a month later:

“It was very strange. I finally got a call from them and they said ‘Come on down here, he wants to see you now,’ so we drove on down to Victorville and it’s the strangest thing you’ve ever seen. First, they bring me into this dark room and Larry’s laying in the bed on the far side of it. Just one dim lamp. I can hardly make him out and they won’t let me get near him. We talked for a few minutes, and he tells me he’s getting better. Then the doctor tells us we have to leave. My mother and I go back to Los Angeles, and two days later I get another call saying he’s dead.”

She says of the funeral arrangements:

“They called me and told me Larry had special instructions as to how he wanted his funeral and I was to follow them to the letter.”

The instructions his wife stated: He wanted a closed casket before he was cremated. Only six people could attend the funeral – his wife and mother-in-law, a particular friend, “a Christian Science Reader” and “her assistant,” and the mortician.

No one knows where Semon’s ashes are. The popular belief/ theory is that Larry Semon faked his own death to dodge creditors, lawsuits, and financial debt. He had filed for bankruptcy before he died. He owed, according to IMDB “just over $2,000,000 in 1920s money.” You’ll find some interesting newspaper articles about Semon on Nitrateville – just scroll down a tad. Semon is still quite popular in Europe.

![]()

![]()

Saint Suttle

Saint Suttle was born in Kentucky in February 1870. Not much is known about this very talented man.

One of two actors in the silent short, Something Good – Negro Kiss (1898), the oldest filmed intimacy between two African American actors. The performance between Suttle and Gertie Brown recreates the original short, The Kiss (1896), by Thomas Edison. The film was popular in the minstrel circuit. Most minstrels and, unfortunately, mainstream Hollywood films at that time portrayed African Americans in stereotypes. This film, however, “is deliberately subverting the racism inherent in American minstrelsy.” (Check out Part I of Appalachians in Moving Pictures for more on Gertie Brown.)

Suttle acted and sang with “a quartet called the Rag-Time Four.” He was also a writer of music. He wrote the lyrics and music for “Old Jasper’s Cake Walk” and “That Creole Gal of Mine.”

He was married three times to Mary L. Murdock, Eliza Bell, and Goldie Smith.

Saint Suttle died February 4, 1932 in Chicago, Illinois. His death certificate mentions his occupation as “laborer,” and doesn’t acknowledge his incredible entertainment career on stage, or his film debut in Something Good.

![]()

![]()

Henry B. Walthall

Henry B. Walthall was born Henry Brazeale Walthall in Shelby County, Alabama on March 16, 1878. His family was quite wealthy.

His father, Junius Leigh Walthall, was a captain in the Confederate Army. After the war, he entered politics. One source says he became a sheriff in Shelby County.

Initially, Walthall studied law at Howard but dropped out to pursue acting. He fought in the Spanish-American War, and made his way to Broadway after the war ended. He had a successful career on stage before he ventured into moving pictures.

D.W. Griffith claimed Walthall was one of his favorite leading actors, saying he “is a rare creation of God, that mankind should appreciate and respect. In all my associations with actors, I can justly say that Henry Walthall, as a photoplayer, is inimitable.” Griffith cast Walthall as “Little Colonel,” Colonel Ben Cameron, in his highly controversial movie, The Birth of a Nation (1915). Not too long after this movie’s release, Walthall left both the production company and Griffith. The actor tried his luck with Balboa Pictures. He and his wife also established the production company, The Union Feature Film Company in 1917, but it met little success. He went forward with Balboa, and also acted with Essanay Film Manufacturing Company. He went back to D. W. Griffith but Walthall found his career had made a downward turn and he was cast in low-budget movies, aka “Poverty Row” pictures. The website devoted to the actor stated that because Walthall left Griffith, “His career, which undoubtedly would have developed along the spectacular lines of those of Lillian Gish, Mae Marsh, and Richard Barthelmess, came to a sudden standstill, and he wasted a decade in interesting but minor films quite unworthy of him.” The implication was clear. Had he stayed with Griffith, he would’ve risen to ultimate stardom.

Nevertheless, Walthall was popular with moviegoers and he did make a great amount of movies – B or not. His transition into sound went well due to his “distinguished bearing” and “stage-trained voice, rich and clear.” Talkies rejuvenated his career somewhat, though it did take a little time to do so.

Walthall was married twice, to Isabel Fenton and Mary Charleson (until his death).

Henry B. Walthall died of influenza and exhaustion on June 17, 1936 in Monrovia, California. He had already “collapsed” right after finishing the role of Dad Brunn in China Clipper (1936). He was told to give up the role for his health but he “insisted on completing the picture before entering the sanitorium.” He was receiving better roles and felt he could reach stardom once again.

**Image source: Tom Mix in The Untamed, 1920 IMDB