People wondering what all the fuss is about concerning J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy and Ron Howard’s screen adaptation of the book will find answers to that query in Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy, a series of essays by diverse voices about a variety of topics bringing Appalachia to the forefront of national attention in these politically explosive times. Editors Harkins and McCarroll announce the scope of their project, acknowledging that the shadow of Hillbilly Elegy hangs over their book:

. . . the contributors address from a range of perspectives an array of pressing questions the Hillbilly Elegy phenomenon raises: What about Vance and his book accounts for the explosion of interest in Appalachia and its people in this historical moment of national political turmoil? Why have the ideas in Hillbilly Elegy caused such a firestorm in the region? What can we learn about both actual Appalachia and the way it is perceived from these reactions and debates? What does it mean in the twenty-first century to be Appalachian? Perhaps most significantly, as poet Jeff Mann explicitly asks here in his poem “Social Capital,” what other Appalachian voices have been drowned out in the flood of attention that Vance and his book have garnered? (p.3)

The reasons for the popularity of Vance’s book are far from surprising. Prominent “conservative intellectuals” spent plenty of political and economic capital guaranteeing that Vance’s Horatio Alger, “pull yourself up by the bootstrap,” message grew wings with the aid of expansive media attention. The agenda they pushed was one bottom-line statement that Vance makes in Hillbilly Elegy: “Public policy can help, but there is no government that can fix these problems for us. These problems were not created by corporations or governments, or anything else. We created them and only we can fix them.” (255-56) (One wonders whether Vance has heard of coal wars, gun thugs, and decades of ruthless industrial exploitation?) Vance’s culture of poverty platform found support in high places, as Appalachian Reckoning contributor Dwight Billings notes:

The reasons for the popularity of Vance’s book are far from surprising. Prominent “conservative intellectuals” spent plenty of political and economic capital guaranteeing that Vance’s Horatio Alger, “pull yourself up by the bootstrap,” message grew wings with the aid of expansive media attention. The agenda they pushed was one bottom-line statement that Vance makes in Hillbilly Elegy: “Public policy can help, but there is no government that can fix these problems for us. These problems were not created by corporations or governments, or anything else. We created them and only we can fix them.” (255-56) (One wonders whether Vance has heard of coal wars, gun thugs, and decades of ruthless industrial exploitation?) Vance’s culture of poverty platform found support in high places, as Appalachian Reckoning contributor Dwight Billings notes:

In a New York Times review, Jennifer Senior described Vance’s “tough love analysis of the poor who back Trump” as “a compassionate, sociological analysis,” and in the same newspaper David Brooks hailed Hillbilly Elegy as “essential reading for this moment in history.” Conservative commentator Rod Dreher went even further, stating that “for Americans who care about politics and the future of our country, Hillbilly Elegy is the most important book of 2016.” Writers at the Economist must have agreed, suggesting “You will not read a more important book about America this year.” Even Larry Summers got into the act, calling Hillbilly Elegy “the most important book for understanding American inequality.” (p. 41)

Billings cites commentators opposing these views:

Robert Kuttner, for instance, claimed that Hillbilly Elegy is nothing more than “a conservative infomercial, disguised as an affectionate memoir,” and another described it as “a vicious little book, a litany of well-worn complaints against the intemperate and shiftless poor disguised as a hardscrabble personal narrative.” Describing Vance as “the liberal media’s favorite white trash-splainer,” Sarah Jones called him, “the false prophet of blue America.” Writing more personally, Betsy Rader, currently a Democratic candidate for Congress in Ohio, described herself in the Washington Post as “an older, female version of Vance” – a single mother born in poverty in Appalachia and raised in Ohio who, like Vance, graduated from Ohio State and Yale Law School. Nonetheless, she took great exception to Vance’s argument that, in her words, “his family and peers are trapped in poverty due to their own poor choices and negative attitudes.” Cutting right to the heart of Vance’s politics, she wrote, “With lines like ‘We choose not to work when we should be looking for jobs,’ Vance’s sweeping stereotypes are shark bait for conservative policymakers. They feed into the mythology that the undeserving poor make bad choices and are to blame for their own poverty, so tax payer money should not be wasted in programs to help lift people out of poverty.” (p.41)

Contributor Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia, analyzes the potentially deleterious influence of Hillbilly Elegy’s popularity in appearing on college syllabi and in university first-year reading programs. She worries that the book’s persistent and pernicious stereotypes are going unchecked:

The New York Times has written that Hillbilly Elegy is a natural choice for universities wishing to buck liberal trends, but the popularity of Hillbilly Elegy among liberal readers is a well-noted phenomenon. The Economist recently identified Hillbilly Elegy as a book that spanned political divides, placing it in the same category as Arlie Russell Hochschild’s Strangers in Their Own Land and Susan Bordo’s The Destruction of Hillary Clinton. Despite Vance’s conservative credentials, the Economist found, using data supplied by online retailer Amazon, that Hillbilly Elegy’s readership was actually more left-leaning than right. The scope and tone of media coverage that has contributed to Vance’s meteoric rise to fame confirms his popularity among liberal readers, and Hillary Clinton recently endorsed Vance’s insight about cultural decline in her memoir What Happened.

The malleability of Hillbilly Elegy’s political logic is, in my view, both sinister and clever. Hillbilly Elegy blankets fundamentally right-wing observations and diagnostics in a compelling personal story intended to present those insights as hard-earned, authentic, and politically neutral. Despite graduating from Yale University, boasting a circle of mentors that include Charles Murray, Peter Thiel, Amy Chua, and Steve Bannon, and commanding a sphere of influence than [sic] stretches from Silicon Valley to Washington, Vance nonetheless consistently projects himself as a sort of “hillbilly” everyman still growing out of his naivety, and is frequently received as such, with praise, by both liberals and conservatives alike.

Acknowledging the broad appeal of Hillbilly Elegy to those on both the left and the right and the utility of this gift to college administrators is an important facet in understanding the book’s transformation from popular memoir to educational text. This phenomenon also suggests that our institutions of learning might have an Appalachia-sized blind spot in their worldview, one in which simplistic narratives and monolithic representations flourish without the scrutiny normally demanded by higher education. (p. 66)

Misconceptions abound about Appalachia, and Catte grasps that inaccurate portrayals sometimes disguise an insidious agenda.

The astute reader may wish to ask what Vance overlooks or fails to notice in his hardscrabble Appalachian/Rust Belt landscape. Blackness is what. In Fact, blackness is conspicuous by its absence, making Vance the great white hillbilly hope who supplants identity politics while restoring poor whites to their proper place in a hierarchy of the nation’s cares and concerns. If the author’s skyrocketing book sales and gushing reviews tell us anything, the message is that even white liberals can justifiably feel ashamed for neglecting the systemic oppression of hillbilly “deplorables” who, though situated in privilege due to their whiteness, derive few advantages afforded by privilege. Is it any wonder J.D. Vance’s people are so volatile or, as African American comedian Chris Rock puts it, “Ain’t nothing scarier than angry white people.”

Lest we forget this simmering population of the poor white working class, Vance reminds us it was they who triumphed in 2016 with Donald Trump’s election to the presidency. They succeeded in enshrining whiteness above all else. As Appalachian Reckoning contributor and historian T.R.C. Hutton states:

Hillbilly Elegy is about whiteness, and the failure of American capitalism to give whiteness the natural purchase it once promised, but Vance seems to think that “white” is not a race, but rather the absence of race. This is something to consider in understanding how he utilizes “hillbilly,” a term with no explicit racial association but an age-old gnomic interchangeability with whiteness. Vance uses “hillbilly” uncritically to describe the people in Jackson, Kentucky, and Middletown, Ohio, and . . . takes the whiteness of his subjects as a given; ethnic heritage seems to be one of the main factors that makes Vance’s hillbillies do what they do. For over a century, “hillbilly” has been used liberally but has very rarely been applied to a nonwhite person. (p. 28)

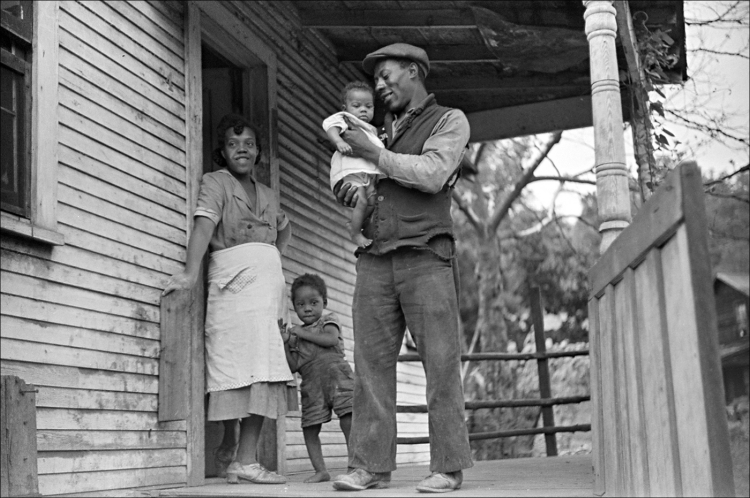

Does that mean black hillbillies don’t exist? Far from it, though Vance artfully dodges the subject, prompting another Appalachian Reckoning contributor, William H. Turner, to offer an inclusion titled “Black Hillbillies Have No Time for Elegies.” Turner begins by acknowledging that Blacks were the original underclass in America:

The press gives Vance profuse recognition and high praise for his family stories even as he holds them responsible for their misfortunes. One generous reviewer noted that his people “did not step off the Mayflower and become part of America’s ascendant class.” To that, I quote Malcolm X: “We didn’t land on Plymouth Rock, Plymouth Rock landed on us.” The fact is that blacks like my people were the initial underclass in America. Vance believes that “learned helplessness” and a pervasive fatalism have invaded what he calls hillbilly culture and proceeds to argues [sic] that because too many hillbillies have endured hard times and adversity for too long, too many of them feel that there is nothing they can do to change their lot. It is easy to focus on the pessimism and estrangement of Appalachia’s underclass, white and black, or for that matter, of any working-class people anywhere in America. But unlike Vance, I opt instead to focus on the socioeconomic realities that explain poverty as a structural, systemic issue. In a capitalist economy, the choices of government policy makers and the corporations that lobby politicians play a large role in both creating and maintaining poverty. (p. 238)

Turner grasps the singular truth that Black Appalachians have always been invisible and don’t enjoy the notoriety – good or bad – that Vance’s white hillbillies receive:

Vance ignored African American working-class people; and by excluding them, he missed a critical point of reference because their experiences could have given his family a warning as to what was coming and how to survive it. As Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. famously said, as though he too had been raised in Harlan County, “I have been to the mountaintop, and looked over; I may not get there with you, but we will get to the Promised Land.”

Hillbillies like the ones Vance remembers – and eulogizes – can and will reach the Promised Land. That is, only if hillbillies, and those who seek to understand us, don’t take too seriously these craftily though deceitfully written premature autopsies of Appalachian people like the one composed by J.D. Vance. (p. 243)

Whatever else can be said, J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy is a cultural phenomenon, one inadvertently exposing fractures in the American social foundation. Unfortunately, Hillbilly Elegy offers no solutions to problems that the book purports to unmask. Just the opposite. Vance deliberately omits the intersectionality of race and poverty in Appalachia, exacerbating existing conditions by the very act of ignoring them. Vance can never bring himself to say what author and activist Will D. Campbell once said: “Poor whites chose the wrong enemy in choosing to hate poor blacks.” Nefarious, too, is the way Vance aligns himself with eugenicist and Bell Curve author Charles Murray, who espouses compulsory sterilization as a condition for anyone receiving federal assistance. Like Donald Trump, J.D. Vance exploits the people for whom he pretends to have great affection, even going so far as to recommend they not reproduce.

The contributors to Appalachian Reckoning are people invested in the region – its problems and progress. They are scholars, activists, and authors with no agenda other than to scrutinize Appalachia unflinchingly. They are not absentee landlords, nor are they seeking the instant celebrity that Vance achieved with the aid of well-heeled political and media backers. More than one contributor urges us to question the faux sentiment that Hillbilly Elegy asks us to accept at face value. Of course, that requires us to shed caricatures and to discover homegrown talents like those assembled in this collection. With a generosity characteristically Appalachian, editors Harkins and McCarroll share their aspirations for Appalachian Reckoning and their vision for the future of Appalachia:

May this collection of scholarship, poetry, photography, and personal narrative remind us all that there is and always has been space to differ, to disagree, to protest, to rage, to reimagine, to commemorate, and to learn. There is space for all of us to reclaim Appalachia as it is for us. And there is a desperate need for the fierce hope embedded in these grounded critiques, humorous anecdotes, and captured moments. Let this book inspire a fierce hope for Appalachia. (p. 13)

**Featured Image: Storm Cell Over the Southern Appalachian Mountains – NASA

Excellent review, and I like the quote from Will Campbell, especially in light of the Trump phenomenon.