I’d like to begin here by saying I am not a linguist. I have studied a small portion of linguistics, enough to understand a smidgen of what I respectfully consider a complex discipline. Thanks to our Associate Editor, Edward Francisco, who graciously gifted his library to me (one of my greatest treasures), I have several sources on linguistics, words, and language.

No, I am not a linguist. Who and what I am, though, is 100 percent, unabashedly a blended assortment of what is Appalachian. I’ll share a broad genealogical history here; research is ongoing. My European ancestors first came to this land before it was even a country in around 1648. Like many forebears (slave, indentured, free, or fleeing), they landed in ports from New York, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina. The earliest date my ancestors came to or were born in these Appalachian Mountains was between 1670-1692. They originated, again like many, from England, Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Switzerland, Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Bohemia (in present-day Czech Republic). I have Melungeon roots and Native American lineages, specifically Cherokee and Shawnee, from the early 1700s.

So, why am I divulging all this extraneous information? I’d like to point out that “Appalachian English” may be plural: Appalachian Englishes. Our English is a mixture of inherited languages from a variety of countries intertwined over hundreds of years up to this Present-Day English. Michael Montgomery says in Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community1)Montgomery, Michael. 2013. “The Historical Background and Nature of the Englishes of Appalachia.” In Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community, edited by Amy D. Clark and Nancy M. Hayward. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.:

Although the English language called Appalachian is often believed to be the most distinctively regional variety in America and is often referred to as if it were a single homogeneous entity, the region does not have just a single dialect. The population’s ancestry is quite mixed, and in many ways, the English of Appalachia represents a microcosm of American English; its speakers have both preserved forms that are no longer used in most of the rest of the country and innovations of others.

Appalachian English is a bit different from state to state, and, should one care to whittle down further, our language may be different inside local communities. A word might be said or defined one way, yet persons one county over may pronounce or use the same word differently. The meanings of some words or phrases are collectively understood – “Appalachian Universal,” if you will. Others are similar, but off. For example, if a picture is uneven, one person might say the picture’s sigogglin’ while another person might say it’s sidelin’. Another example: My father was an extremely observant man. He was trained to be, given his profession in law enforcement. An inebriated person might be “higher than a Georgia pine.” But, to my father, that person was “higher than a kite in a Georgia pine on Sunday.” Still, some words are altogether strange and different. (One of the words in this quiz attests to that fact – but we’re all going to have to find out in the next post.)

Appalachian English words may also have unique usages or meanings in addition to the conventional English word. The word fur, for example, is defined as “the coat of a mammal” or “a coniferous tree.” In Appalachian English/ vernacular, the word fur also means “far” or “a distance,” as in “Well now, so and so lives a fur piece away from here.” Or take the word holler, a word that traditionally means “to yell,” but in Appalachian English, the word also means a backwoods place in the mountains.

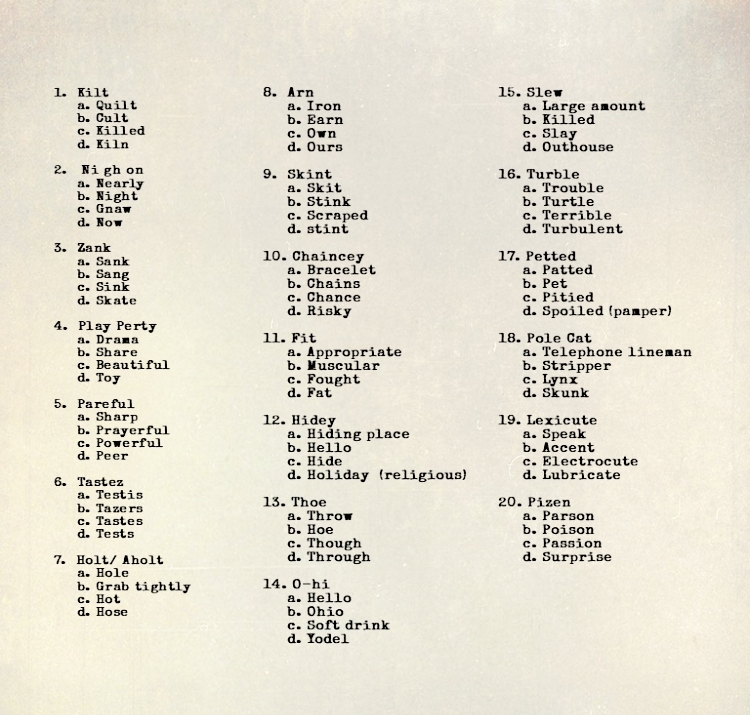

However one puts it, Appalachian English has a plethora of global origins. Take Appalachia Bare’s newest quiz and see if you recognize your ancestral vocabulary. Please bear in mind – Appalachian English is not always conventional English. And, if you’re feeling froggy, try your luck with our first, second, and third quizzes!

Introduction by Delonda Anderson

QUIZ

Visit us next week to find out the answers!

**Featured image from www_slon_pics on Pixabay

References

| ↑1 | Montgomery, Michael. 2013. “The Historical Background and Nature of the Englishes of Appalachia.” In Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community, edited by Amy D. Clark and Nancy M. Hayward. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. |

|---|

Oh wow I just found….well this amazing website…..mind if I share to my genealogy groups? I wanted to ask you, have you ever heard of this southern phrase, I used to say papaw how you feeling…..his response “oh, fair to middlin”….I love it!!!!

Hello Valerie. I’m so glad you are enjoying our site. Please, by all means, share this little venture of ours with anyone. We rely much on word-of-mouth. I have heard the phrase you mentioned, but with one slight difference: “fair and to middlin’.” I think the oddest phrase I ever heard was from my father. No one I know has ever heard it said quite the way he said it. He was a police officer for most of his life. If he ever saw someone inebriated, he’d say they were “higher than a kite in a Georgia pine on Sunday.” I’ve heard “higher than a kite.” I’ve also heard “higher than a kite in a Georgia pine.” But he is the only person to say “on Sunday.”