One day, I’d just hung up the phone after talking with my mother, and my oldest son asked,

“Mom, how come you talk different when you’re on the phone with Mammaw?”

“Do I?” I asked, puzzled. My youngest son chimed in,

“Yeah. You do. You talk more country. It’s weird.”

I have to tell you I didn’t see it at all. I still don’t. But I believe and agree that I do. (The irony is on another occasion my mother told my brother: “She don’t talk like us no more.”)

But my sons’ curiosity made me wonder. Why do I speak differently to my mother? In the book Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community, edited by Amy D. Clark and Nancy M. Hayward, the notion of “voice place” is explored.1)Clark, Amy D. and Nancy M. Hayward, ed. Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2013.p. ix “Our speech is home.” Yet, a huge difference exists between “home speech” and “away speech.” Why is that?

The fact is that many of us accommodate our dialect to “fit in” our surroundings. But, Clark and Hayward say this is damaging. Such adaptation begins in education’s “Standardized American English” teaching. If a student was taught “about the origins, linguistic structure, and rich literature associated with her ‘voiceplace,’” she would better understand herself and her own origins.2)Clark, Amy D. and Nancy M. Hayward, ed. Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2013.p. ix

Appalachians are often discriminated against, labeled as uneducated, and therefore dumb. For example, how many times has a comedian used Appalachian or Southern vernacular to make a joke about some ignorant person? This treatment is, in effect, “linguistic bigotry” or “linguistic prejudice.”

Linguistic bigotry stems from ignorance about how language is constructed, its place in society, and the human tendency to project prejudicial attitudes about a group of people by attacking a cultural trait such as language. For this reason, perhaps more than any other, many Appalachians have struggled with the concept of an Appalachian identity . . .3)Clark, Amy D. and Nancy M. Hayward, ed. Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2013.p. 4.

Of course, our nation has a history of language denigration: Native American,4)The U.S. government forced Native American children to participate in programs where “their barbarous dialect should be blotted out and the English language substituted.” (Clark & Hayward p. 3) African American Vernacular English, Irish brogue (particularly in the 1800s), Latino dialects (i.e., “speak American,” or, “English-only”).5)Clark, Amy D. and Nancy M. Hayward, ed. Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2013. p. 4

Think back for a moment to our German, Scotch-Irish, Southern European, and African American (slave and free) settlers. Languages markedly affected local dialects, creating sub-dialects. A known fact is that instances of Appalachian English can be traced “before Chaucer,”6)Wolfram, Walt. “Is There an “Appalachian English”?” Appalachian Journal (JSTOR) 11, no. 3 (1984): 215-24. and proof exists that some Appalachian English is Elizabethan. But it is so much more. One might say several Appalachian Englishes exist.7)Clark, Amy D. and Nancy M. Hayward, ed. Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2013. p. 8 One source branded the dialect as “Appalachian Amerenglish.”8)Wolfram, Walt. “Is There an “Appalachian English”?” Appalachian Journal (JSTOR) 11, no. 3 (1984): 215-24.

Let’s return to the school system and to the aforementioned student. Teaching only Standardized American English (i.e., “proper English”) and labeling other dialects “as ‘incorrect’ will lead to their extinction.” Taking away Appalachian dialect or saying it’s “bad” English removes “an integral component of personal and social identity.”9)Clark, Amy D. and Nancy M. Hayward, ed. Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2013. p. 16, 18

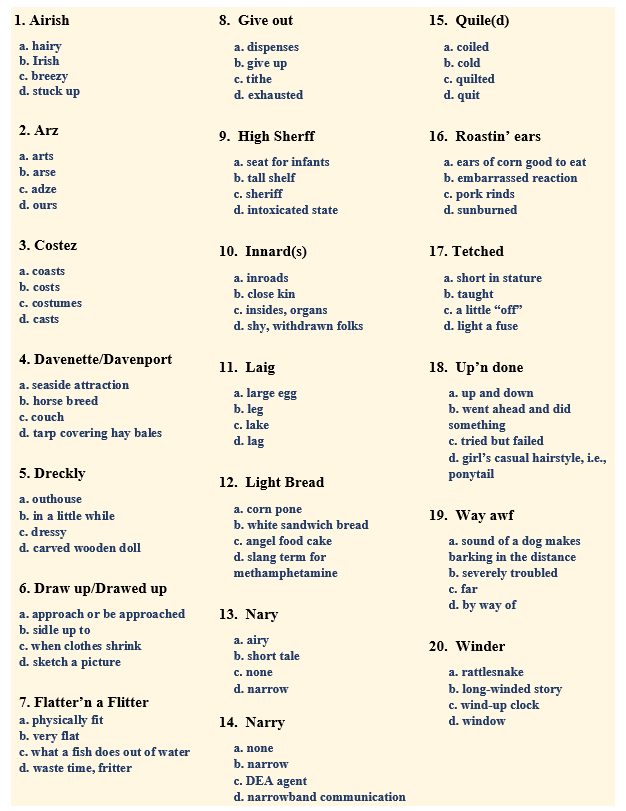

Take the quiz below to see how “schooled” you may be in Appalachian English:

** Featured Image from Snappygoat

References

| ↑1, ↑2 | Clark, Amy D. and Nancy M. Hayward, ed. Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2013.p. ix |

|---|---|

| ↑3 | Clark, Amy D. and Nancy M. Hayward, ed. Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2013.p. 4. |

| ↑4 | The U.S. government forced Native American children to participate in programs where “their barbarous dialect should be blotted out and the English language substituted.” (Clark & Hayward p. 3) |

| ↑5 | Clark, Amy D. and Nancy M. Hayward, ed. Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2013. p. 4 |

| ↑6, ↑8 | Wolfram, Walt. “Is There an “Appalachian English”?” Appalachian Journal (JSTOR) 11, no. 3 (1984): 215-24. |

| ↑7 | Clark, Amy D. and Nancy M. Hayward, ed. Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2013. p. 8 |

| ↑9 | Clark, Amy D. and Nancy M. Hayward, ed. Talking Appalachian: Voice, Identity, and Community. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky, 2013. p. 16, 18 |