My mom has a chestnut tree in her new backyard. I know because I came across dozens of little spiky somethings spread on the ground and I was concerned that her dog might step on one (or more) and get hurt. I brought one into her house. We debated as to what it could be until my mom said,

“I believe it’s a chestnut tree. Your daddy used to talk about how hard it was to open’m up and get out the chestnut. There was one down the holler at G—‘s house. Probably dead by now.”

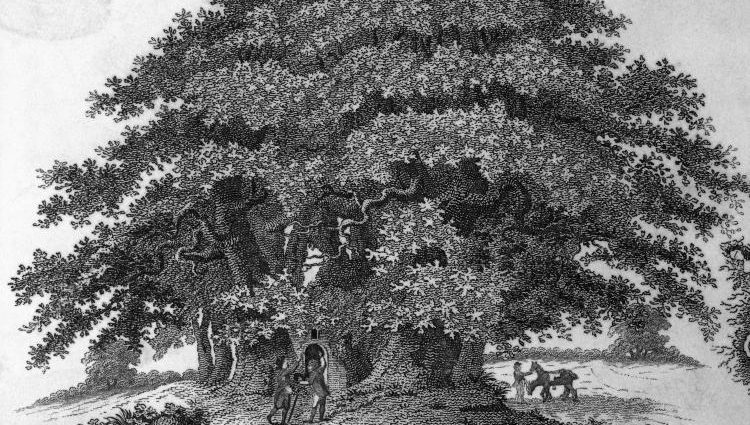

I knew from stories I’d heard about chestnut trees the value I held in my hand. I brought one of those hulls home with me and I keep it like a precious treasure. My mom’s tree is probably part of the restoration project to bring back the chestnut. But, when I hold the outer covering in my hand, I often imagine myself underneath one of the old ones before the blight, gazing upward, awed by its immense splendor.

At one time a person walked through the Appalachian mountains among an abundant forest of mammoth American Chestnut trees (some so big you might live in them). As a matter of fact, the tree made up about a quarter of the Appalachian forest. It was a massive feat of nature’s ingenuity, standing a mammoth one hundred to one hundred twenty feet tall, with branches beginning no less than fifty feet up. It was considered “one of the leading hardwoods of America.”1)Buttrick, P. L. (1915, Oct). Commericial Uses of Chestnut. American Forestry: The Magazine of American Forestry Association, 21(262), 960-67. Lumber companies, saw mills, and carpenters profited from its wood because it was lightweight, yet strong, and didn’t warp.2)Buttrick, P. L. (1915, Oct). Commericial Uses of Chestnut. American Forestry: The Magazine of American Forestry Association, 21(262), 960-67. Not to mention the roasted chestnut was a beloved snack and an enhancement to holiday stuffing.

At around 1904, New York imported the Chinese Chestnut tree to the United States, and, unbeknownst to anyone, it carried the fungus, Cryphonectria parasitica. The scourge killed about four billion of the colossal American Chestnut trees.3)Nickens, T. E. (2012, Sept). The Lord of the Forest. Retrieved April 3, 2013 The Appalachian region lost much in the way of insect and animal habitats. Chestnut wood never again created furniture or provided house lumber. Sawmills no longer sank metal teeth into its much-coveted lumber. Its seeds no longer provided food for deer, bear, or humans. According to the Citizen Times article, “For chesnuts, life follows death,” the Southern region’s economy as a whole lost much when the tree’s chestnuts and lumber were no longer available. The loss was deep and the fact that the stamina of this beloved tree was taken for granted cut even deeper. Throughout Appalachia (Northern, Central, and Southern) and its surrounding region, studies were hurriedly conducted, and reports and commissions were quickly formed to try and save the American Chestnut, all to no avail.

The main and, frankly, most amazing restoration project for the American Chestnut tree comes from The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) in a procedure called, “backcrossing.” This process was first successfully performed in the 1970s by Dr. Charles Burnham and involves cross breeding the Chinese and American Chestnut trees, then painstakingly removing all but the blight resistant characteristics found in the Chinese Chestnut tree, thereby keeping much of the American Chestnut tree’s characteristics intact.4)Weisberg, D. (2012, April 10). Coaxing American Chestnuts Back to Appalachia. Retrieved April 3, 2013, from NewYorkTimes.com Over the last thirty years, TACF has produced seeds that they hope will begin the re-population of the American Chestnut tree in Appalachian states like Tennessee, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio. One fascinating aspect of this process is the pollination method used to protect the hybrid trees in the growing experiment. Volunteers pollinate each flower by hand with “pollen from the desired strains of backcrossed trees.”5)Nickens, T. E. (2012, Sept). The Lord of the Forest. Retrieved April 3, 2013 The American Chestnut Foundation has also partnered with various federal Forest Services, the Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative, and the Agriculture Department’s Natural Resources Conservation Service.6)Weisberg, D. (2012, April 10). Coaxing American Chestnuts Back to Appalachia. Retrieved April 3, 2013, from NewYorkTimes.com

Though most all botanists and dendrologists don’t foresee the American Chestnut tree reclaiming its former glory, nature is always full of surprises. And human intervention’s meticulous care to restore this great, ancient behemoth is a positive and admirable accomplishment – an especially reassuring feat amidst humankind’s ongoing history of nature destruction – and one success of many for hopeful nature lovers.

**Featured Image Source: Diego Footer’s Permaculture Voices/ Woody Agriculture – Breeding Trees, Restoring a Piece of America’s Past and Establishing a Piece of Our Agricultural Future with Phil Rutter – Part 1 of 2

References

| ↑1, ↑2 | Buttrick, P. L. (1915, Oct). Commericial Uses of Chestnut. American Forestry: The Magazine of American Forestry Association, 21(262), 960-67. |

|---|---|

| ↑3, ↑5 | Nickens, T. E. (2012, Sept). The Lord of the Forest. Retrieved April 3, 2013 |

| ↑4, ↑6 | Weisberg, D. (2012, April 10). Coaxing American Chestnuts Back to Appalachia. Retrieved April 3, 2013, from NewYorkTimes.com |

Thanks for this very informative history of the American Chestnut. Another sad story of unintended consequences. I excitedly told a Nature Conservancy forester about a chestnut sapling I had discovered in Biltmore Forest. He informed me that finding a sapling was not that unusual, but these trees (that are not hybrids) rarely make it to adulthood before the blight gets them.

I’m glad you liked it, Jim. It really is a sad story, especially given they were admired for their great size and strength. I took a look at the chestnut tree in my mom’s backyard and saw quite a few dead branches. So, it looks like that one might be a non-hybrid that survived a few years at least.

Let’s be hopeful!

Yes! Nature is always full of surprises. Sometimes animals or plants or trees thought to be extinct suddenly appear again.

Some good news about Appalachian trees in The Washington Post Magazine that includes interviews from the local communities. This may require a subscription, so here’s a WP blurb about the article: “After the ravages of mountaintop removal, can trees revive the land and the economy? Patrick Angel spent decades overseeing the destruction of Kentucky’s land. After a painful epiphany, he’s devoting himself to making Appalachia green again. But he has even bigger ambitions: to put not just the forest but the broken Appalachian economy back together.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/lifestyle/magazine/appalachia-kentucky-reforestation/?utm_campaign=wp_todays_headlines&utm_medium=email&utm_source=newsletter&wpisrc=nl_headlines