Rebecca Harding Davis

Rebecca Harding Davis was born in Washington, Pennsylvania, on June 24, 1831, and spent her first five years in Big Springs, Alabama. In 1836, her family moved to Wheeling in what would become West Virginia. When she was fourteen, she was sent to the Washington Female Seminary in Pennsylvania. In 1848 she returned to Wheeling and joined the staff of the Wheeling Intelligencer.

In 1861, Davis submitted “Life in the Iron Mills” to the Atlantic Monthly, where it was published. Davis’s first novel, Margaret Howth, was published in 1862. In 1863 she married Clarke Davis, an attorney who corresponded with her after reading “Life in the Iron Mills.” In 1864, the first of their three children was born. They lived in Philadelphia, where her husband was editor of the Inquirer.

Davis published more than ten novels. Her autobiography, Bits of Gossip, was published in 1904. The Feminist Press published a new edition of “Life in the Iron Mills” (1972), for which Tillie Olsen wrote the Introduction. Davis died on September 29, 1910, at the home of her son, Richard Harding Davis, in Mount Kisco, New York.

Biography by Edward Francisco

from The South in Perspective: An Anthology of Southern Literature by Edward Francisco, Robert Vaughan, and Linda Francisco

![]()

A Stifled Working Class: Space and Light in Rebecca Harding Davis’s “Life in the Iron Mills”

Here, inside, is a little broken figure of an angel pointing upward from the mantel-shelf; but even its wings are covered with smoke, clotted and black. Smoke everywhere! A dirty canary chirps desolately in a cage beside me. Its dream of green fields and sunshine is a very old dream,—almost worn out, I think.1)Davis, Rebecca Harding. 1995. A Rebecca Harding Davis Reader: “Life in the Iron Mills,” Selected Fiction & Essays. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 3

The canary in Rebecca Harding Davis’s, “Life in the Iron Mills,” sits trapped and rather listless in its soot-covered cage and its predicament seems to symbolize the story’s central theme. The story takes place in an unknown industrialized area and paints a more realistic picture of everyday nineteenth century labor and the industry’s effects on the working poor. “Life in the Iron Mills” was published at a time that coincided with the Industrial Revolution. The magazine’s readership was a privileged, upper class who enjoyed the features of American Romanticism in art and literary aestheticism, the picturesque, particularly in poverty, and nature-filled pastoral settings. The obtrusive narrative voice in “Life in the Iron Mills” forces that elite audience’s attention to the lower working class who are smothered inside an ever-shrinking and polluted environment. Some of the story’s readers were likely the very factory owners who perpetuated and preserved the lower working class’s dire situation. In “Life in the Iron Mills,” Rebecca Harding Davis uses liminality and light to expose industry’s prolongation of lower working class squalor.

The Industrial Era was a time of great expansion and wealth, but people of the working class, like those in Davis’s story, saw little benefit from such progress. Factory work meant long, hard hours for low wages. Workers came home to unsuitable housing. Poverty, starvation, and sickness were the norm. The canary and humans share similar quandaries in “Life in the Iron Mills.” They are both covered with factory filth. Both are weakened and miserable in their cramped situations. Both are forced to live and view the world from a confined space. The canary has a cage and the humans have their own “cage” of an industrial city and system. They both hunger to escape into the open, clean, crisp air. Instances of space and light in “Life in the Iron Mills” seem to emphasize the working poor’s conditions. Characters look at life through windows, travel pathways to reach the other side, and walk between doorways.

. . . from the street-window I look on the slow stream of human life creeping past, night and morning, to the great mills. Masses of men, with dull, besotted faces bent to the ground, sharpened here and there by pain or cunning; skin and muscle and flesh begrimed with smoke and ashes . . .2)Davis, Rebecca Harding. 1995. A Rebecca Harding Davis Reader: “Life in the Iron Mills,” Selected Fiction & Essays. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 3, 4

The Quaker hesitated, but only for a moment. She put her strong arm around Deborah and led her to the window.

“Thee sees the hills, friend, over the river? Thee sees how the light lies warm there, and the winds of God blow all the day? I live there,—where the blue smoke is, by the trees . . .”3)Davis, Rebecca Harding. 1995. A Rebecca Harding Davis Reader: “Life in the Iron Mills,” Selected Fiction & Essays. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 32

An invisible border exists for the reader, a liminal in-between state that allows the narrator and characters to view life between spaces. Stand by a window. On one side of the window is poverty. On the other side of the window is a possible hope. Walk down a path with eyes ahead. On one side of the pathway, life is suffocating. The other side offers good, clean air. Stand at a threshold. One side of the doorway is candlelight. The other side is pitch blackness.

From the benign room in the house, the narrator opens the window and focuses the reader on the other side’s misery. The narrator influences the reader to become an active observer wrapped up in the setting and in the characters’ lives. After the narrator’s introduction, Davis uses the old house where the Wolfes lived as a crucial starting point for the family’s tale. Yet she also connects the characters with a sense of yearning. Protagonist Hugh Wolfe, for example, a furnace tender in his thirties, lives with his father, Old Man Wolfe, and his cousin Deborah in a two-bedroom cellar dwelling. Hugh grasps his current socio-economic status but longs to be in a clean, light place with the rested, refreshed upper middle class. One might argue that a liminal border exists in his mind between a tired destitute place and his desired upper class place.

In her chapter, “Windows: Looking In, Looking Out, Breaking Through,” from the book, Thinking on Thresholds: The Poetics of Transitive Spaces, Gillian Beer asks, “What is a window? framed space? A liminal connection between inner and outer?” She answers:

“. . . the window registers connection and difference between the interior and exterior . . . the window can express in literary works the social reality of privilege and exclusion.”

“Life in the Iron Mills” begins at a window where the narrator’s descriptions of the town’s dingy atmosphere seem to separate both narrator and reader from the window’s other side. So, right from the start, the reader feels safe and somewhat distanced from the rank odor, the incessant soot and smokiness, and “the slow stream of human life creeping past,” on their way to the mills. The narrator summons the reader to awareness by “idly tapping the window-pane,” emphasizing how difficult it is to see through the fog, smoke, and rain. The taps also underscore the window’s liminal space, further drawing the reader’s attention to the boundary that exists.

The Wolfe family’s small, cramped space enables the reader to experience the working poor’s inescapable and ever more increasing confinement. Narrowness minimizes the working poor’s space as living becomes smaller and smaller until space takes almost a symbolic undertone that represents not only the loss of freedom, but also the fact that freedom never existed for them in the first place. The working poor are trapped in the mire of economic inequality that separates them from the upper class.

Liminal space seems to bookend the story near the ending. Hugh, serving a nineteen-year sentence for money theft, sees the outside world through his jail cell window. The in-between state of ultimate confinement and wishful freedom are represented in heartbreaking scenes, particularly when he watches the marketplace activities. He hears the ironic “clink of the money” and even tries to push his face through the bars, to seemingly break through the liminality, in order to get closer to the marketplace scene. The cell window’s liminal space represents a freedom or dream Hugh will never attain. The despairing Hugh ends his own life. In contrast, the Quaker woman later opens the same jail window after Hugh dies, and brings in “woody” scented plants for the “fresh air” to breeze across. The Quaker woman then draws Deborah to the window and shows her a different way of life from the industrialized mills. The Quaker woman, who is seemingly positioned as a Christian moral lesson for the audience, gives Deborah an option, a way out. For Deborah, the window’s liminal space exists as the border between her despair and her hope.

The elite nineteenth century reader would be very familiar with windows and thresholds in their spacious homes with rooms galore. He or she might be accustomed to walking nonchalantly between the thresholds. However, thresholds in “Life in the Iron Mills” seek to sever that nonchalance by replacing it with the lower class threshold. When Deborah opens her cellar door and crosses the threshold into her home, a place most might consider a haven, the living conditions become shockingly clear. The room is dark, damp, and plainly toxic with its “slimy” dirt floor and foul air. Crossing a threshold generally signifies change, but not always positive change. The cellar door’s liminal space stresses a situation where the “bad” space outside the door crosses over into a “worse” space inside. The in-between gives no real hope for Deborah, further revealing how trapped working class people are. To be sure, people of all classes have passed through thresholds, opened doors, and peered out windows. Even the eye has been deemed a “window.” But the world looks different from small, dark, cramped spaces.

As liminality provides that invisible border between industrialism and nature, poverty and wealth, griminess and cleanliness, light works to expose it all—from the gleam of Deb’s small “tallow dip”, to the iron mill’s hellish light, to the final scene’s bright sunshine.

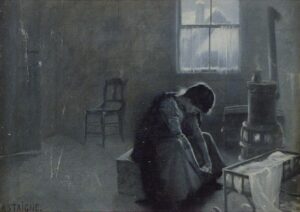

Deborah groped her way into the cellar, and, after considerable stumbling, kindled a match, and lighted a tallow dip, that sent a yellow glimmer over the room. It was low, damp,—the earthen floor covered with a green, slimy moss,—a fetid air smothering the breath.4)Davis, Rebecca Harding. 1995. A Rebecca Harding Davis Reader: “Life in the Iron Mills,” Selected Fiction & Essays. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 6

Though both darkness and light exist in “Life in the Iron Mills,” light, whether small or large, fire or sun, illuminates the poverty, the oppression, the hard labor, the sun-filled Quaker community, and even darkness itself. In the cellar, for example, Deborah’s “tallow dip” gave the room a “yellow glimmer” glow, and its lighting suggests just how dark the room actually was—and how dark it remains. Further, the light really isn’t much light at all as it exposes a dull, yellow, weathered view of the surroundings. The Wolfes are destitute, tired, and sick in this environment. Light illuminates their meagerness, exhaustiveness, and nothingness.

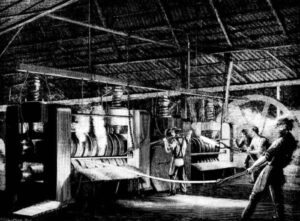

When Deborah walks down the “narrow street” in the dark, a few gas lamps “flicker” over the “uncertain space.” Once she reaches the iron mill’s “city of fires,” the story’s tone shifts to a more chaotic one. She is encompassed by the fires, with their flames, sparks, liquid, and smoke. The hellish red light accentuates the awfulness of the men’s labor, exposing the sweltering and oppressive work that endlessly drains their body and spirit. The red light makes the laborers look “like revengeful ghosts,” almost inhuman. Flames from both iron mill and candle enlighten the reader to a sense of the working poor’s domestic and economic sphere. Light illuminates their cramped, moldy, scant living spaces and their hot, smothering, smoke-filled work spaces. The characters cannot catch a break from this gloomy situation, not even when a worker’s long shift is over.

The mills for rolling iron are simply immense tent-like roofs, covering acres of ground, open on every side. Beneath these roofs Deborah looked in on a city of fires, that burned hot and fiercely in the night. Fire in every horrible form: pits of flame waving in the wind; liquid metal-flames writhing in tortuous streams through the sand; wide caldrons filled with boiling fire, over which bent ghastly wretches stirring the strange brewing . . . .5)Davis, Rebecca Harding. 1995. A Rebecca Harding Davis Reader: “Life in the Iron Mills,” Selected Fiction & Essays. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 3

Davis hoped to change things by exposing the nineteenth century elite reader to the dire situation of the working poor’s lives. She does so in a frank and jolting manner. In an interview published in Women Authors of Our Day in Their Homes, Davis admits, “If you want a reader to see a thing you must slap him in the face with it.”6)Halsey, Francis W. Women Authors of Our Day in Their Homes: Personal Descriptions and Interviews. New York: J. Pott & Company, 1903. Web. 15 Mar 2015. Her methods seem appropriate for an apathetic audience who tended to either blame the poor for their situation, or neglected to see their humanity at all. Terms used by activists and city officials to describe the Industrial Era pollution, such as “contaminated” or “corrupted,” were eventually used to describe the working poor who lived and worked inside the poisoned environment.7)Gatlin, Jill. “Disturbing Aesthetics: Industrial Pollution, Moral Discourse, and Narrative Form in Rebecca Harding Davis’s ‘Life in the Iron Mills’.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 68.2 (2013): 205. Web. 08 Mar 2015.d

To the upper class, these dirty working people were the actual filth in which they lived. Davis seems to take this belief and turn it on its head by revealing the characters in “Life in the Iron Mills” as “the human incarnation of the pollution in the eyes of many a nineteenth-century reader.”8)Gatlin, Jill. “Disturbing Aesthetics: Industrial Pollution, Moral Discourse, and Narrative Form in Rebecca Harding Davis’s ‘Life in the Iron Mills’.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 68.2 (2013): 209. Web. 08 Mar 2015.d In other words, the story’s working poor embody a visual, tangible, walking pollution maintained by the upper class. The narrator’s careful treading and prodding, along with the story’s ability to create rapt attention, forces the reader to see the actual lives of the people they neglected or denigrated for far too long.

So, we come back to the beginning, back to the canary—a relatable creature with its static, in-between liminality, the narrowness of its cage, and the diminished light from smoke, fog, and soot. Davis seems to remind the elite reader that the upper class cannot continue neglecting this demographic of society. If they do, she implies, social justice either falls apart or rebellion ensues.

Sources:

- Nina Baym and Robert S. Levine, eds. The Norton Anthology of American Literature 8th Edition. New York: W. W. Norton , 2012. Print.

- Gillian Beer. “Windows: Looking in, Looking Out, Breaking Through.” Mukherji, Sugha. Thinking on Thresholds: The Poetics of Transitive Spaces. London: Anthem Press, 2013. 3-16. Web. 3 Apr 2015.

- Rebecca Harding Davis. 1995. A Rebecca Harding Davis Reader: “Life in the Iron Mills,” Selected Fiction & Essays. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Jill Gatlin. “Disturbing Aesthetics: Industrial Pollution, Moral Discourse, and Narrative Form in Rebecca Harding Davis’s ‘Life in the Iron Mills’.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 68.2 (2013): 201-233. Web. 08 Mar 2015.d

- Francis W. Halsey. Women Authors of Our Day in Their Homes: Personal Descriptions and Interviews. New York: J. Pott & Company, 1903. Web. 15 Mar 2015.

- Sharon Harris. “Rebecca Harding Davis: From Romanticism to Realism.” American Literary Realism 21.2 (1989): 4-20. Web. 03 Mar 2015.

- Richard A. Hood. “Framing a ‘Life in the Iron MIlls’.” Studies in American Fiction 23.1 (1995): 73-78. Web. 08 Mar 2015.

- Andrew Lyndon Knighton. Idle Threats: Men and the LImits of Productivity in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: New York UP, 2012. Web. 09 Mar 2015.

- Maribel W. Molyneaux. “Sculpture in the Iron Mills: Rebecca Harding Davis’s Korl Woman.” Women’s Studies 17 (1990): 157-177. Web. 08 Mar 2015.

References

| ↑1, ↑5 | Davis, Rebecca Harding. 1995. A Rebecca Harding Davis Reader: “Life in the Iron Mills,” Selected Fiction & Essays. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 3 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Davis, Rebecca Harding. 1995. A Rebecca Harding Davis Reader: “Life in the Iron Mills,” Selected Fiction & Essays. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 3, 4 |

| ↑3 | Davis, Rebecca Harding. 1995. A Rebecca Harding Davis Reader: “Life in the Iron Mills,” Selected Fiction & Essays. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 32 |

| ↑4 | Davis, Rebecca Harding. 1995. A Rebecca Harding Davis Reader: “Life in the Iron Mills,” Selected Fiction & Essays. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 6 |

| ↑6 | Halsey, Francis W. Women Authors of Our Day in Their Homes: Personal Descriptions and Interviews. New York: J. Pott & Company, 1903. Web. 15 Mar 2015. |

| ↑7 | Gatlin, Jill. “Disturbing Aesthetics: Industrial Pollution, Moral Discourse, and Narrative Form in Rebecca Harding Davis’s ‘Life in the Iron Mills’.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 68.2 (2013): 205. Web. 08 Mar 2015.d |

| ↑8 | Gatlin, Jill. “Disturbing Aesthetics: Industrial Pollution, Moral Discourse, and Narrative Form in Rebecca Harding Davis’s ‘Life in the Iron Mills’.” Nineteenth-Century Literature 68.2 (2013): 209. Web. 08 Mar 2015.d |